A touring exhibition of sixteen large-scale computer manipulated photographic artworks completed during Colvin’s tenure as Senior Research Fellow in Digital Imaging at the University of Northumbria in conjunction with Impressions Gallery, York. The artworks explore the relationship between fantasy and reality, digital and analogue, and the way photographic image making has become fractured in the late 20th century. Exhibited in venues in York (Impressions Gallery), Southend -on –Sea (Focal Point Gallery), Edinburgh (Portfolio Gallery), Barcelona (Centre Cultural Caixa de Terassa), Salamanca (University of Salamanca), Seville (Centro de Arte Contemporaneo), Manchester (Viewpoint Gallery), North Wales (Theatr Clwyd), Leeds (Leeds Metropolitan University Gallery) and Halifax (Piece Hall Gallery). The exhibition was sponsored by Genix Imaging Ltd, Fujifilm Professional, and the British Council. Work featured in ‘Portfolio’ no. 24, with an essay by David Alan Mellor.

A Package Flight to the Land of the Dead

Calum Colvin’s Pseudologica Fantastica

DAVID ALAN MELLOR

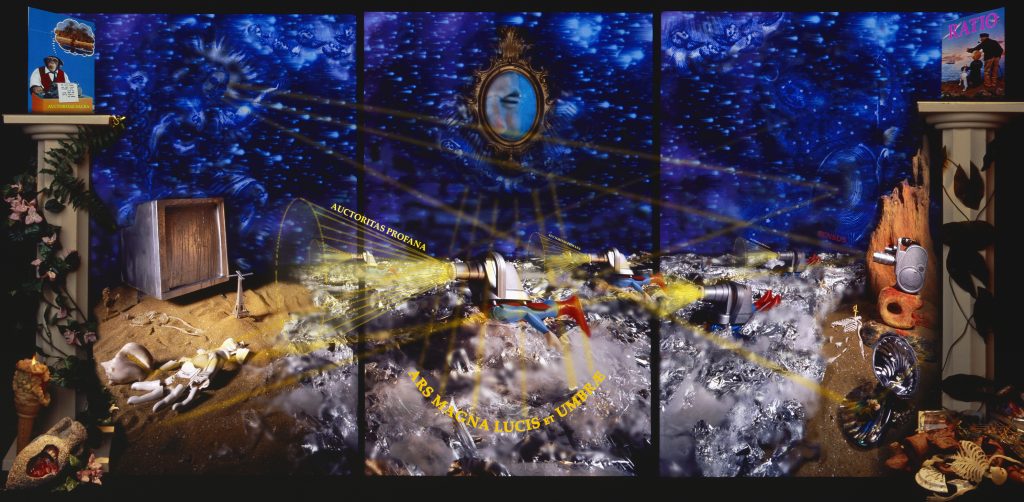

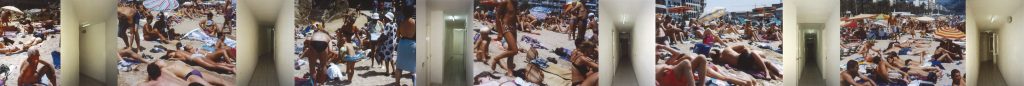

HOLIDAYS FROM hell and holidays to hell. In Calum Colvin’s new series of digitally generated photographs, Pseudologica Fantastica, Spanish tourist hotel corridors and crowded beachscapes have liquified into quicksilver ribbons of madness. Here, holiday memories and siesta intervals fly straight back to purgatory. Colvin’s narrative commences with the banal – the scenography of the Great British package holiday – which then swoops into an endless ruin. His Triptychs 1 and 2 trace, like an unrolled scroll, a racing body of desire made up of sunbathers. This becomes a twister of deformed images, a tornado of whirling and sucking which forcefully constricts itself through architectonic apertures in a sort of peristaltic movement, before returning, like the genie lured back into its flask. It goes back into a yellow dial from the timing mechanism for central heating – a regulator of heat, a fantastic object following in the footsteps of Picabia and Duchamp’s mechanical analogues for desire. Yet at the end of these city triptychs the ribbon of dreams is seen again, but not as a single flowing wave of squeezed images. Now it is infinitely slowed down, separated as single flipped photos, revenants from the Spanish holiday. They stir and fly listlessly through the frames of the mansions of the dead, like Plato’s uncorrupted soul on a visit. In the city of the dead, memory is encoded in and on stone: the monumental pylons that compose Colvin’s subterranean world have disquieting vestiges of events still adhering to them – scorch marks in the shape of human silhouettes and barnacle forms that have traded places with the rocks from the Spanish beach Happy-Snaps.

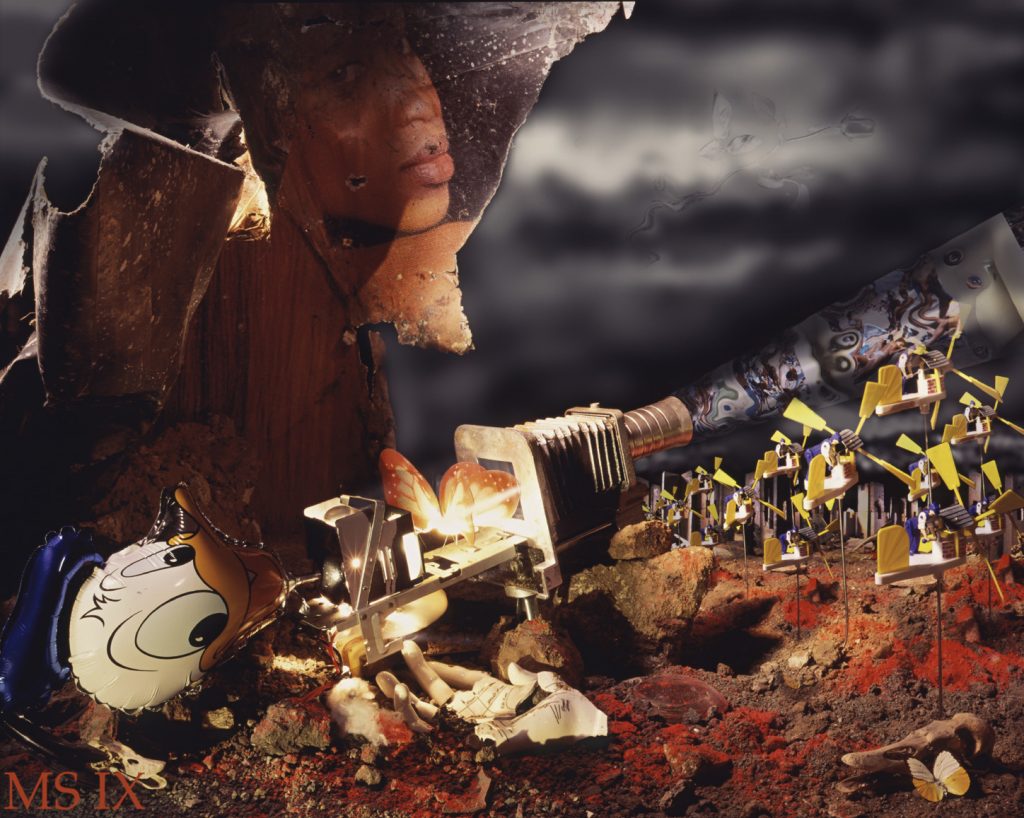

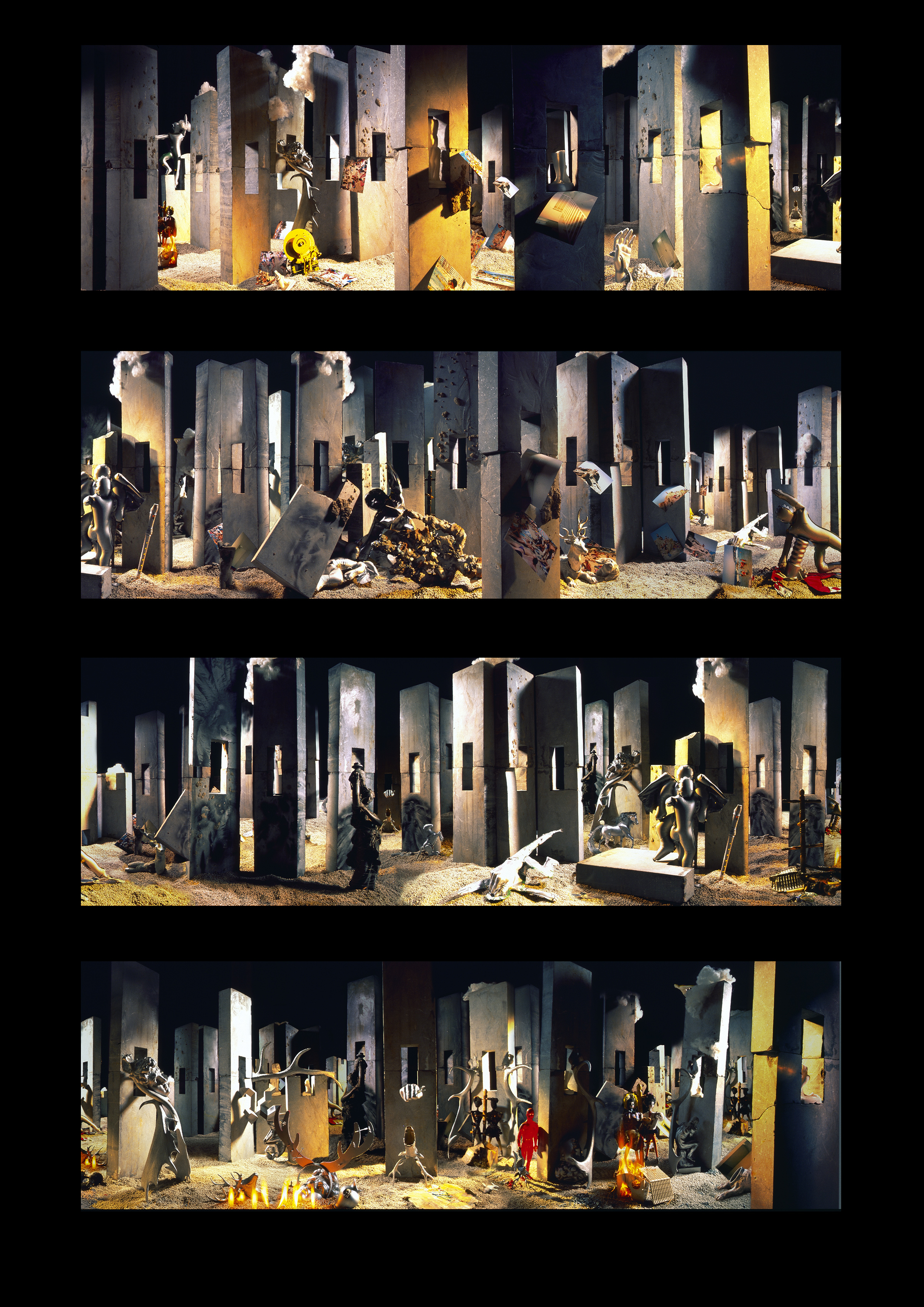

‘Mundus Subterraneus I’ 1996

A certain disgust with the corporeal body (in the age of the virtual) runs at all levels through Pseudologica Fantastica. Examples within the series include the UV- damaged, but still tanning humans on the beach: a spectacle, Colvin has said, resembling ‘a combination of Bladerunner and Blackpool” – the bizarre and the banal together. There is the burnt and shattered hand, as if left on the Basra road in March 1991; the disinterred skull; and the miller’s doomed coupling with the siren in Mundus Subterraneus VI-VIII, which ends in disaster amidst chaotic waves.

Colvin’s newest work has been mainly inspired by the 17th century Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher. His book, The Subterranean World, was a philippic, a denunciation of the alchemist’s culture – from the point of view of an exalchemist – presenting them as ‘a congregation of knaves and impostors’2. Kircher was disillusioned and angry at the failure of the ‘Great Work’ of transmuting the base world: the alchemical project was revealed by him as delusory. Colvin’s cautionary version of Kircher’s subterranean world is titled Pseudologica Fantastica and it, in turn, addresses a prevalent folly of our time. Just as Kircher’s Subterranean World took aim at alchemy, Colvin’s contemporary ‘popular delusion’ is an apocalypticism of the image. His landscapes rebuke the bizarre, the morphed and the Face on Mars, and puts them in a sobered, Dante-esque setting.

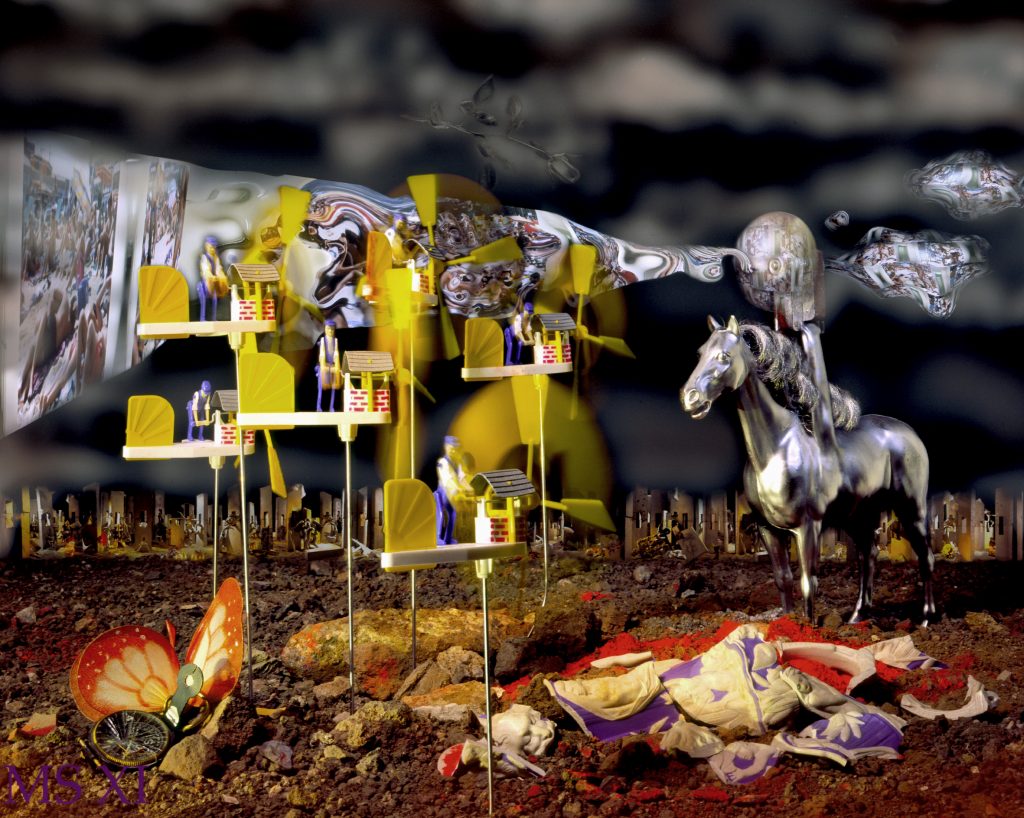

‘Mundus Subterraneus II’ 1996

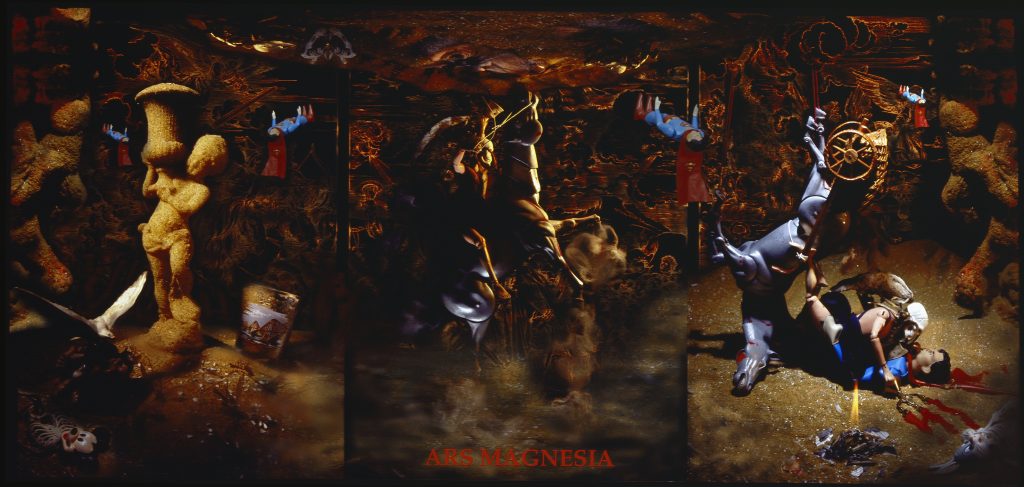

Pseudologica Fantastica disinters and unwindsan ascetic set of grave commentaries by Colvin on our contemporary mortified distractions. The precedent is Urne Buriall, written by another 17th century polymath, Sir Thomas Browne, another cataloguer of bizarre popular delusions, in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica. Browne began his voyage into the customs of the underworld with a paradoxical turn of speech and representation: ‘In the deep discovery of the Subterranean world, a shallow part would satisfie some enquirers…’3 Colvin’s comedy narrative of the miller’s flying machine is perched upon a watery horizon, while Browne named water as ‘the smartest grave’4: he nominated two principal forms of ‘corporal dissolution… simple inhumation and burning’5. In Colvin’s ‘subterranean world’ flames leap up as Ignis Fatuus in the city of the dead. Separately, he has presented the scene of burning with bony claws, scorched paper and rubble. Fiery particles are driven by the imperative to transform the corpse to avoid ‘contagion and pollution’. In Triptych 3 flames leap up in the lair of horrors, with hot red plastic zombies and the agonised Hellenistic heads that we last saw in Colvin’s repertory in his Brief Encounter version of Leighten’s Athlete Wrestling with a Python, in 1990.

This is a world of imperial evolutionary growths that have been dismantled, of vectors and drives which have petered out and run into the desert, returning to inert, stony matter – a devolution from higher to lower. Either the disinterred skull of Colvin’s Mundus Subterraneus is already embalmed, with its brains replaced by curved and chambered photographs of the beach and corridors of Lloret de Mar, or it is a relic of failed inhumation, along with the blasted hand. Browne was writing in 1658 in the wake of the discovery, at Walsingham, of forty to fifty Romano-British burial urns containing ‘…ribs, jaws, thigh bones and teeth’.6 This is what composes the techno-skull in Mundus Subterraneus I, an antler-jawed relic which has fallen into his hands, the hands of an inveterate constructor of tabernacles and oracular

situations since his earliest temple-like contrivances in works such as Cenotaph (1987), The Temptation of St Anthony (1989), and Brief Encounter (1990).

In this new work there is a reversal of expectations about the legibility and substantiality of different forms of imaging; his terminal and interminable beaches, actual and recorded on film, become de-realised by pixillation and digitisation – turned into teardrop reliquaries of our desired images of consumer leisure. Colvin appears to take a posture of mistrust to these scenes of photo-generated representation, a form of scepticism which mortifies the instruments of photography through metamorphosis: the skull as a camera and a photographer’s tripod as the forearm support of a dead hand.

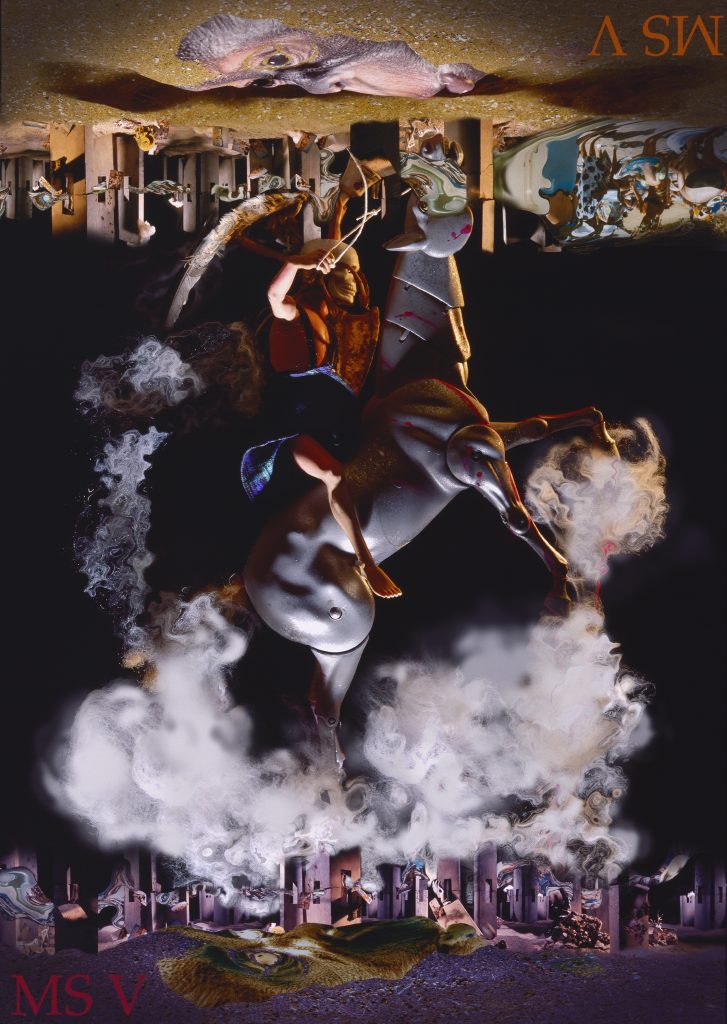

The scenography of a wasteland, populated with corpses and menacing relics that have not yet returned to cycles of decomposition, has its prompts in T. S. Eliot. ‘What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow I Out of this stony rubbish?…(T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, lines 19-20). ‘That corpse you planted last year in your garden / Has it begun to sprout?… with nails he’ll dig it up again’ (lines 71, 75). The obtrusive return of dead organic matter is thematised by the rise of an ashen rose in the sky in Mundus Subterraneus IX, resembling one of David Hiscock’s post- volcanic bouquets. This blighting effect should be taken together with the blasted photographic flesh found in tatters at the end of the reach of the dead hand. In Mundus Subterraneus V, Colvin’s Scottish rider has been assimilated into the persona of the Angel of Death, but is still thrown by something macabre and essentially base which is stirring from the earth. The rider and horse are suspended between two subterranean worlds with no prospect of progress or direction home, since they are caught in the baleful gaze of that primal ancestor of homo sapiens, the ape. He emerges from the gritty soil above and below, and, in a derisory signal, he sticks his tongue out at the triumphal rider.

With Colvin, the means of producing a photographic or screened and scanned image arises directly from the ravaged but technologically augmented body. For example, the camera bellows protruding from the spinal column in Mundus Subterraneus II projects a central nervous system with a capacity to generate pictures like Max Ernst’s levitated female statue in La Femme Cent Tetes (1929)7, which exposes ‘the means of this illusion’s production’.8 Into the spine of Mundus Subterraneus II are pouring a reservoir of images from a floating globe. These photo-images are of deserted beaches and sunset-lit gateways – pictures purged of the sordid proximities of bodies found in his Lloret de Mar beach photos. The scenes are of a purified and atmospherically charged home – the streets and beach of Colvin’s Edinburgh suburb of Portobello – and they are smokily decanted like an alchemic liquor flowing into the projector. Another such melding of parts comes with the passage from the Angel of Death’s feathered wings to the ectoplasmic ribbon of leisure dreams and nightmares, in Mundus Subterraneus V.

Mundus Subterraneus IV carries questing, sporting and erotic narrative fragments that are present on the weathered and stained TV screens broadcasting them into the barren world, like the grey disused PC monitors in Ars Magna. The central screen in Mundus Subterraneus IV reads ‘The End’, blazoned across an eerie electronically-transmitted version of the enclosed Spanish hotel corridor. That corridor vanishing point, a repeated place of reverie for the eye amidst the crowded sequence of bodies, becomes a point of ingress, doubled by those split monumental masonry blocks of the town of the dead, through which the ribbon of images flow. The image arises from another bizarre metaphor of an unburied body part – a group of rigidly inflated plastic toy hearts, lying on beds of candy-floss, which are grounded forever in the subterranean world.

- 1. Calum Colvin to the author, 12 October 1996, York.

- 2. C. McKay. Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, 1995, Wordsworth, Hertfordshire, p.213

3 Ed. Sir Geoffrey Keynes. Sir Thomas Browne/Selected Writings. Faber and Faber, London. 1970, p.110.

- 4. Op. cit. p.119.

- 5. Op. cit. p.120.

5. Op. Cit. p.124.

- 7. Reproduced by R. Krauss. ‘The Im/Pulse to See’, ed. H. Foster, Vision and Visually. Bay Press. 1988, p.56.

- 8. Krauss, op. cit. p.55.