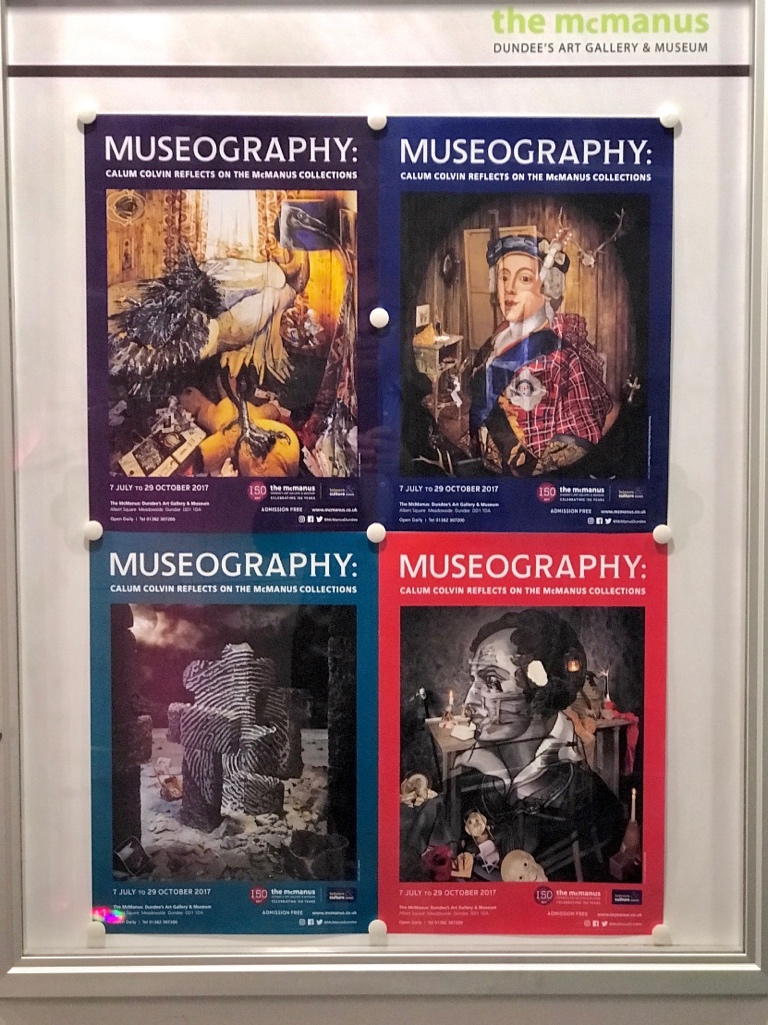

Location: The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum.

Dates: Friday 7th July to Sunday 29th October 2017.

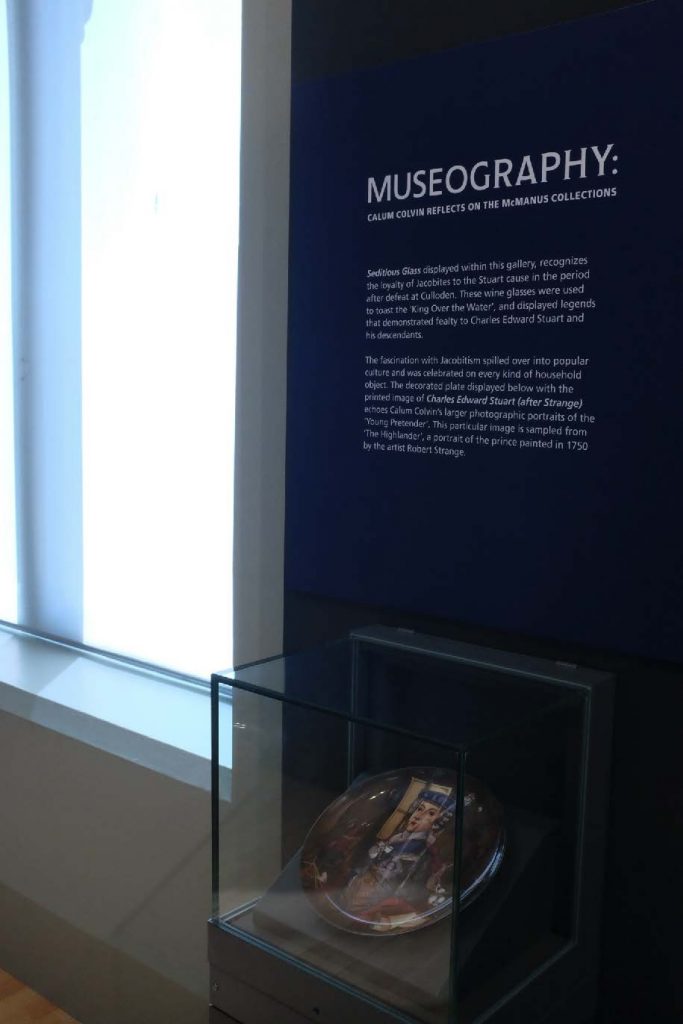

Museography was a solo exhibition commissioned as part of a year-long programme marking the 150th Anniversary of The McManus, Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum.

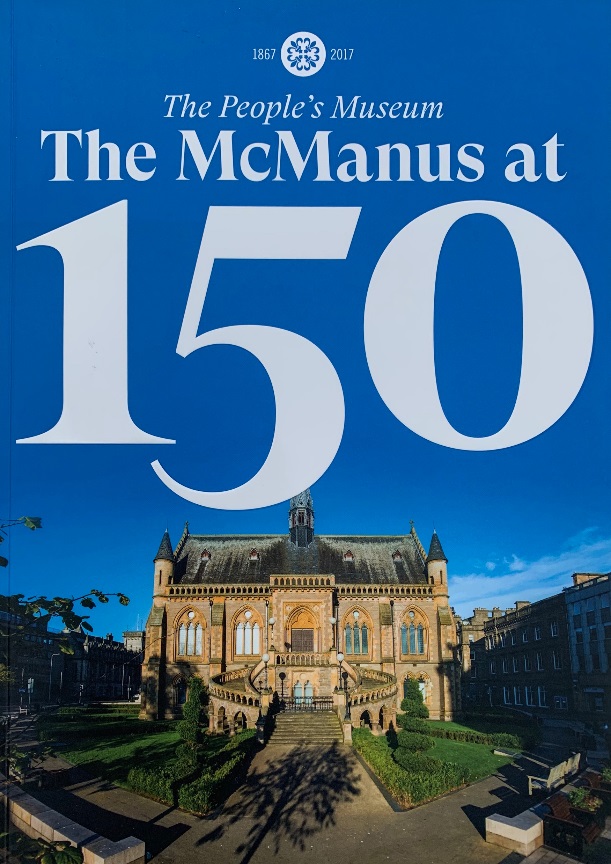

The museum is a 150-year-old Gothic Revival jewel designed by George Gilbert Scott (who built London’s St Pancras Station). A library and gallery devoted to the advancement of science, literature and art, its Gothic balustrades, stained glass windows and pyramidal roof turrets speak to the city’s self-confidence when it was riding high on 19th-century trade, shipbuilding, jute milling and whaling. The McManus is a multi-themed museum in a beautiful 19th-century building.

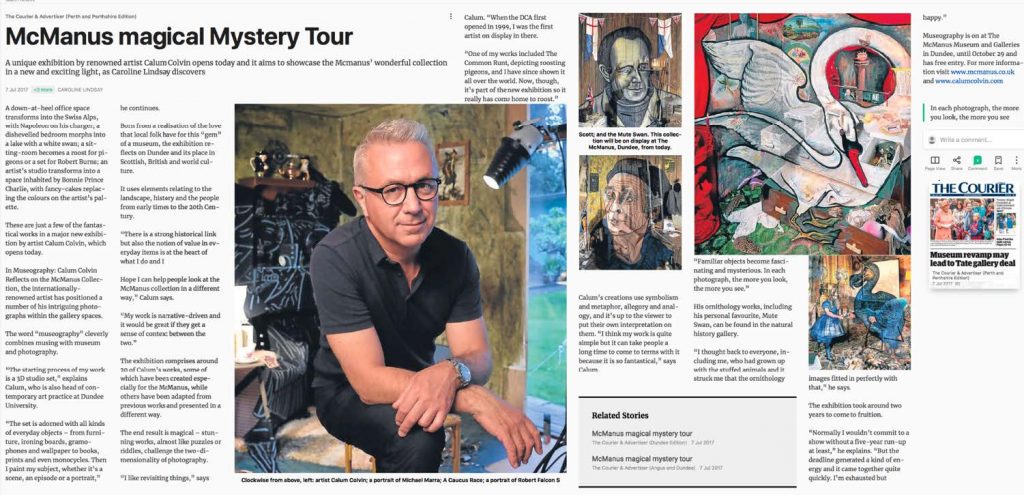

The exhibition/intervention comprised of twenty works juxtaposed with historic paintings and positioned strategically throughout the galleries, this ‘collection-withina-collection’ interrupted the viewing experience to create a contrast between the ambivalent visual nature of artworks and their typological classification. The exhibition provided a visual framework for an alternative reading of historical artworks to allow a critical reassessment of Scottish national histories from today’s vantage point.

The research in The McManus included creating a series of stereoscopic photographs, embroidery and objects that restage and revision well-known historic paintings, adding contemporary resonance to them. Amongst the works was a new photographic reconstruction of John Petties’ 1877 ‘Disbanded’, which restages a Romantic vision of a returning Jacobite soldier into a scene dwelling on recent political events in Scotland. Another example is the ‘re-presentation’ of William Bradley Lamond’s portrait of William McGonagall, the famous 19th century ‘bad poet’ of Dundee, as a stereoscopic tragic/comic hero. Other portraits included Dundee bard Michael Marra, alongside a display of ephemera relating to his life, and a portrait of Captain Robert Falcon Scott, sits alongside his nemesis in Polar exploration Roald Amundsen, within the display commemorating Dundee’s maritime history.

My personal memories of McManus stretch back to when I first came to Dundee as a student at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design in 1979. At that point, Dundee was a little down at heel, suffering particularly in the general economic decline. There were lots of derelict buildings around and the McManus’ Gothic splendour was looking a little faded, certainly when we compare it to its current reincarnation!

Of course, as a young art student with a passion for photography that aesthetic of urban decay in itself was interesting to me and inspired many photographic expeditions under the tutelage of the great Joe McKenzie. As I got to know my new Dundonian friends, it was interesting to get their view on the city, and I noticed that there was a great deal of affection for the McManus, especially the gallery (now called Landscapes and Lives I) which houses the natural history exhibits. This struck a chord with me, reminiscent of my own childhood fascination with museum culture and its effect on the youthful imagination: our first close up view of the natural world, of the history of cities, of the wonders of engineering are often shaped by these institutions! This is especially true with the McManus, which connects so wonderfully with the history and culture of Dundee.

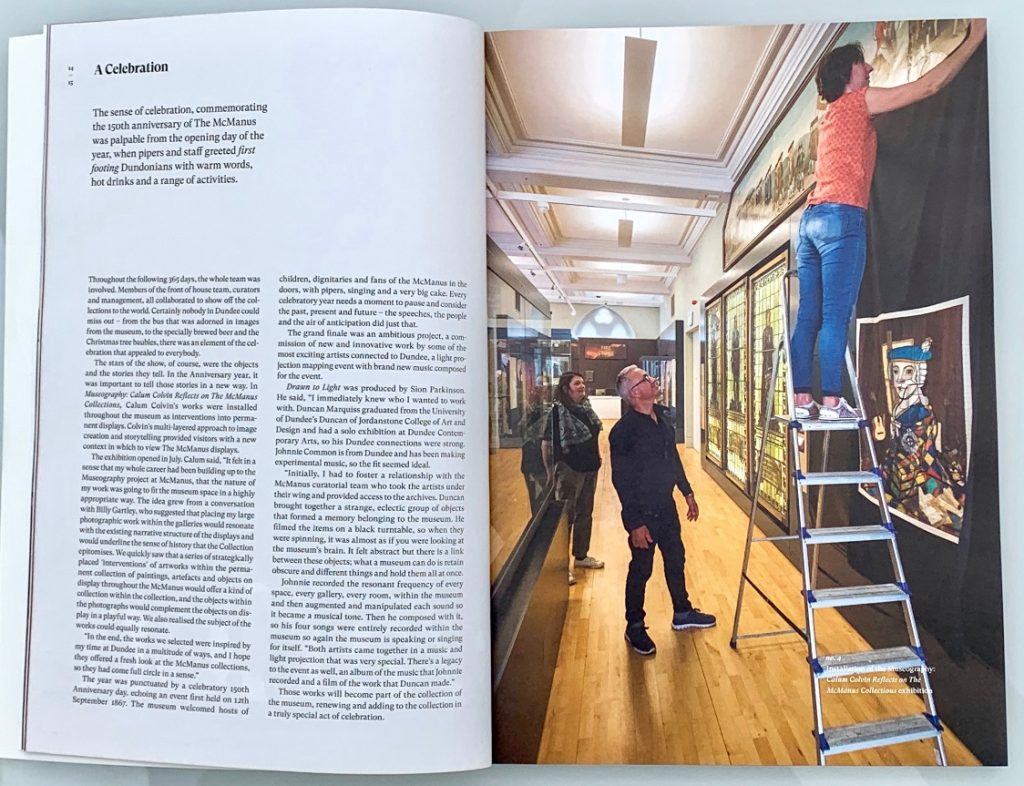

With this history in mind, it felt in a sense that my whole career had been building up to the Museography project at McManus, that the nature of my work was going to fit the museum space in a highly appropriate way. The idea grew from a conversation with Head of Cultural Services Billy Gartley, who suggested that placing my large photographic work within the galleries would resonate with the existing narrative structure of the displays and would underline the sense of history that the Collection epitomises. We quickly saw that a series of strategically placed ‘interventions’ of artworks within the permanent collection of paintings, artefacts and objects on display throughout the McManus would offer a kind of collection within the collection, and the objects within the photographs would complement the objects on display in a playful way. We also realized the subject of the works could equally resonate.

In the end, the works we selected were inspired by my time at Dundee in a multitude of ways, and by the McManus collections, so they had come full circle in a sense.

‘Harlequin’ (after Calum Colvin) by Elma Colvin

The exhibition was widely reviewed nationally (including The Scotsman, The Times, The Courier) and attracted 55,036 visitors over four months significantly widening audience engagement with Scottish historical collections. Subsequently, The McManus acquired seven of the exhibited works for its permanent collection with the financial assistance of the National Fund for Acquisitions. Dundee Heritage Trust purchased a further two works for display in the RRS Discovery Visitor Centre and three of the works are now on loan to the office of the Leader of Dundee City Council.

… Calum Colvin has also been invited to mark the McManus’s sesquicentenary, not with an exhibition exactly, but with a series of works distributed throughout the displays.

Artists’ “interventions”, or “responses” of this kind are generally lamentable; their work appears puny and self-absorbed beside real objects imbued with history. But Colvin is different. His work is complex, thoughtful and witty. It is also by its nature allusive and so admirably suited to the role it is given here, not competing discordantly with the museum’s displays, but joining in, broadening the dialogue beyond bald information towards reflection and even poetry.

It is difficult to find a label to describe Colvin’s hybrid way of working. Ultimately he makes photographs, but before he does so, he paints, constructs and assembles objects of all sorts into a scene in which juxtapositions, interactions and overlays all join to create a rich and complex whole finally unified as a photograph. Here different themes are interwoven with various links to the displays, to photography and to the city’s own history and the people who made it. His overall theme however is perhaps memory: how the grand and the trivial are incorporated into history without

discrimination and thence into the myths by which we identify ourselves in our daily lives.

For this reason, perhaps, however far-flung the links, his images tend to be set in very ordinary domestic interiors. Robert Burns, for instance, has become, not just part of our self-awareness as Scots, but even part of the fabric of our lives and so in Colvin’s portrait he floats ghostlike in someone’s sitting-room. The walls are hung with souvenir plates and portraits of Harry Lauder. A chair is piled with editions of Burns’s verse, but the portrait itself is circular and is surrounded in turn with plates adorned with the poet’s portrait, several designed by Colvin himself. Thus our national poet has become part of our material culture. It is a nice point to make in a museum where too rarely we make just that link, though in reverse, to recognise how material objects feed the intangible ideas from which we construct our identity.

Colvin also brings that thought to bear directly on Dundee’s own history. There is a portrait of William McGonagall, the city’s famous bad poet. But Colvin again asks us to look beyond the myth. The portrait is a stereoscopic image, red and green glasses provided. You see McGonagall, quite literally, not in the two-dimensions of the popular image, but in three, in the round in fact and with aspects of his real persona as a travelling showman incorporated into the image.

The Polar explorer Robert Robert Falcon Scott’s association with the city is there in his ship, Discovery, built in Dundee and moored alongside the evolving V&A. Both Scott and his nemesis, Ronald Amundsen, are present here in characteristically allusive portraits.

One of the most telling images offers a commentary on John Pettie’s painting, Disbanded, of a Highland soldier returning home in a wintry landscape. Colvin’s Highlander, however, is a domestic ghost striding through someone’s living room with his foot a sketch on the telly. On the wall is a collection of tourist-style images of other indigenous peoples exploited in the name of Empire while two fat Toby jug imperialists enjoy a casual cup of tea.

In Cruthni, Colvin returns to the theme of indigenous people. The Cruithni were apparently one such Scottish tribe, and he invokes them in a picture hanging behind the museum’s Pictish stones. His image is a battered standing stone in a desolate rocky landscape. It carries neither carving nor inscription, but a huge thumb print, the telltale trace, not just of human presence in general, but of an individual presence, a reminder that the people who inhabited Skara Brae, present in a curling photo, were individuals just like us.

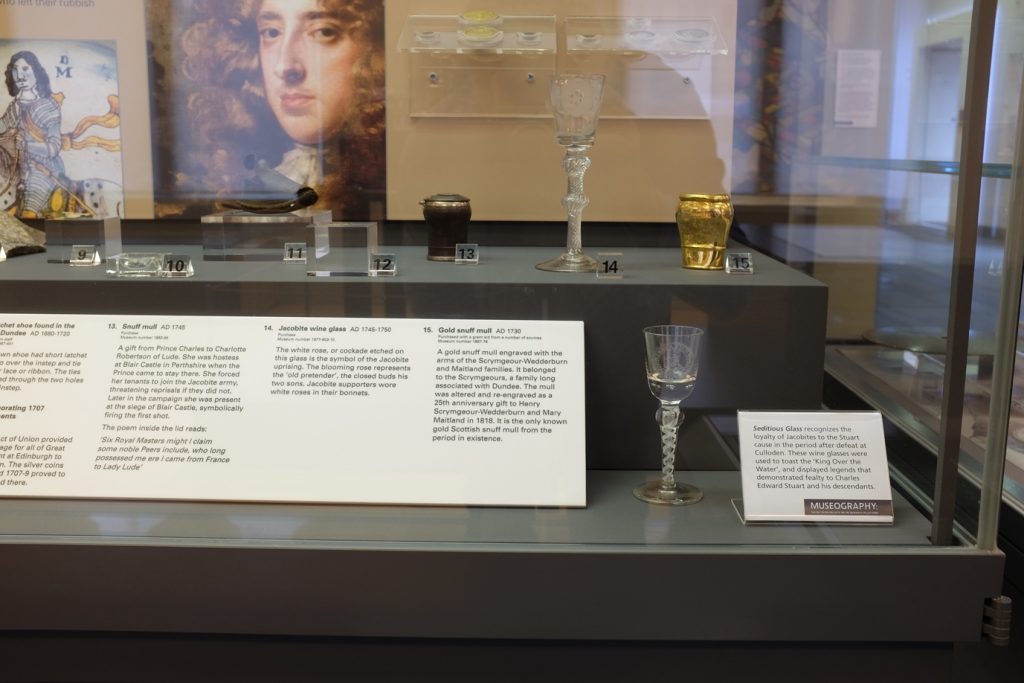

Some of Colvin’s Jacobite images hang among the museum’s Jacobite collection. Unidentified Aircraft is a cloudy homage to Edward Baird’s painting of the same name of a Nazi bombing raid on Montrose. Colvin’s commentaries on photography itself are intriguing too. Most striking is A Caucus Race, an image from Alice in Wonderland, but where Alice meets a dodo, and the dodo it seems is a metaphor for the passing of analogue photography supplanted by digital. It is nevertheless still an object of wonder.

DUNCAN MACMILLAN

‘The Scotsman’ Saturday 5th August 2017

The Courier & Advertiser, July 7th 2017

The Times, July 11th 2017