https://academiciansgallery.org/exhibitions/12-calum-colvin-rsa-constructed-worlds/overview/

Calum Colvin: Constructed Worlds, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh *****

By Duncan MacmillanWednesday, 29th January 2020, 1:31 pm

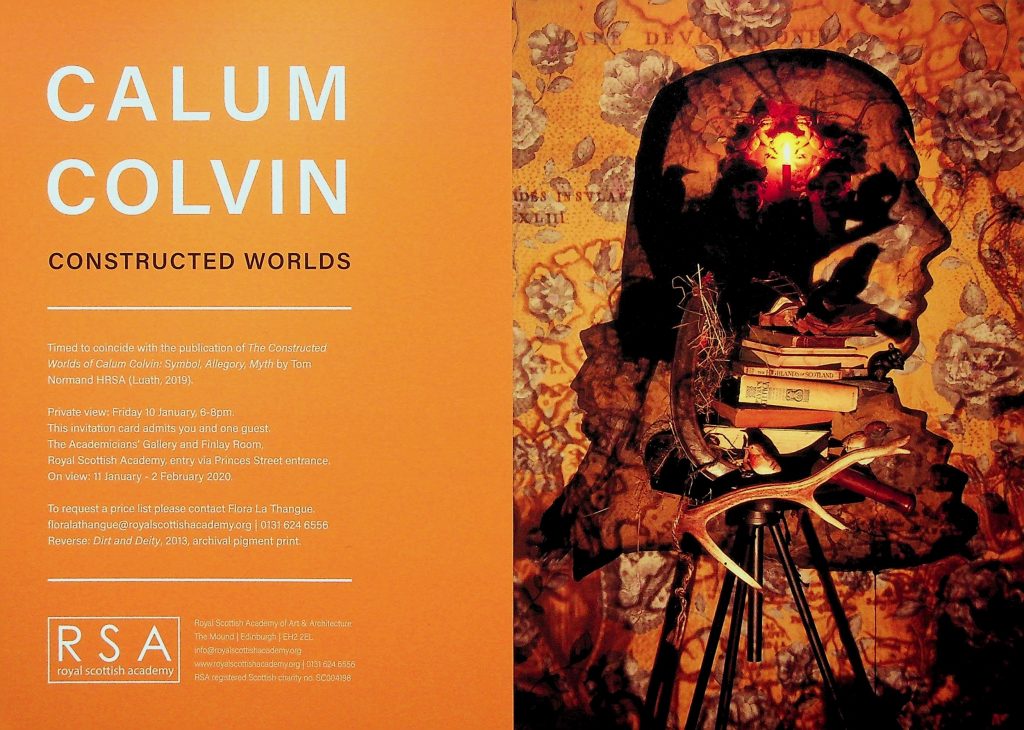

What would moments of reflection, of consciousness, or memory look like, if indeed we ever could record such a thing? Calum Colvin has a shot at it, however, or at least that is what his complex, multi-layered images sometimes suggest: all the diverse threads of a moment of consciousness, memory and reflection brought together in a single image. Just how complex his imagery can be is amply demonstrated in Calum Colvin: Constructed Worlds at the Royal Scottish Academy. The show complements the launch of a book on Colvin’s work by Tom Normand, The Constructed Worlds of Calum Colvin: Symbol, Allegory, Myth (Luath, £25) and although not billed as a retrospective, like the book it is an illuminating survey of his work over the last 30 years and more.

It would be an insult to his sophistication as a photographer to talk about snapshots, but as the word is used to describe a single, captured image of something that is actually complex and transient, it is not entirely inappropriate. Certainly the end product of his process is usually a single photograph, though there are also many variations on this format. Exploring byways of perception he makes the kind of 3D photographs that require red and green glasses, for instance. He also makes anamorphic images. Here, for example, a distorted picture on a horizontal disk becomes a readable image of Bonnie Prince Charlie when reflected on a central vertical cylinder. Still, even with such variations, each work is nevertheless a single and simple proposition. What it actually records is anything but single or simple, however.

Colvin began his career studying sculpture and he remains loyal to that art form, to the extent that he begins with assemblage. Even before that, however, he collects. The assemblages that are the basis of his work always combine an extraordinary variety of ephemera, kitsch ornaments, toys, books, texts, and incorporated images. He also draws directly onto the plate so that his drawing is as much part of the unification of everything as the photograph itself. The artist he most calls to mind is Eduardo Paolozzi. He was also a sculptor who couldn’t be contained by a single art form and whose art was always collage or assemblage and much more than the sum of its parts. More than that, however, Paolozzi couldn’t be contained either by the idea of fine art. Colvin shares with Paolozzi a recognition of how all the innumerable currents of our visual culture are so interwoven that it is ridiculous to suppose the fine art strand could ever stand apart. This proposition underlies his Allegory with Venus and Cupid (after Bronzino) for instance. The Old Master image suggests fine art, but then the work goes on to demonstrate that fine art can claim no monopoly of love, nor even less of sex. Intercutting the central image variations on the themes of love and sex occur throughout the picture, ranging from saucy postcards, a piggy bank in the shape of a whale titled “Sperm Bank” and a bust of Harry Lauder with a slogan beneath, “Happiness is under my sporran.” The pains of love don’t change, however. The main group is sitting first on a very mundane arm chair, but then on a fakir’s bed of nails.

Harry Lauder is part of our constructed identity, of the Scottish self-image with all its idiosyncrasies – a theme throughout Colvin’s work. Bonnie Prince Charlie appears in several guises as an embodiment of the myths from which we have built our identity. In Pretender I-IV, for instance, he morphs from a handsome young prince in armour to a fairground horse called Rebel. In Lochaber No More I-III, the young prince becomes the decrepit old prince. The middle image is anamorphic and shows him as either one or the other, depending on your viewpoint. In Betty Burke, he is disguised as a lady’s maid, the cross-dressing prince. Robert Burns gets the same treatment in several variations, but none of these images is simple. It is the detail, the blending, the cross-referencing and the puns that give them their intellectual and artistic weight. You really do have to read the small print, often literally, whether it is a Shelley fragment or a philosophical treatise with illustrations from Oor Wullie.

While these images deconstruct our identity, they do not simply dismiss it. One touching picture is of the weathered face of Colin McLuckie. A familiar figure from the artist’s youth, he was an ex-miner afflicted with the terrible miner’s disease of pneumoconiosis. He knew Burns by heart and in the picture he is clearly reciting as he would do quite spontaneously to any chance audience. Here he joins Burns, MacDiarmid, Byron and Ossian. Deconstructing our self-image is not to debunk it, but to reflect on its imaginative complexity and the last named, Ossian, is the subject of one of Colvin’s most remarkable works, a set of nine images in which the head of Ossian gradually crumbles into a monumental ruin.

There are two from the series here, numbers I and VIII. With Ossian, the Scots’ search for identity became a potent international example. It was also definitively imaginative even if that word has to cross-over with “imaginary.” These things are at once separate and indivisible and Colvin explores that conundrum at the heart of our identity. Tom Normand’s book offers an illuminating commentary on the whole of his remarkable oeuvre.

Scots identity, or indeed, more specifically what he claimed as his Celtic identity, was also a preoccupation of JD Fergusson. Far from being sentimentally anachronistic, for Fergusson as for Colvin this was part of his uncompromising modernity. In a collection of his drawings presented at the Scottish Gallery by Alexander Meddowes there are vivid works in his familiar mode of rapid portraits in vigorous pencil – women, and disembodied breasts like apples which indeed could be either – but there are also one or two really adventurous works where he explores the radical new language of Modernism. Nor for him was this catch-up. He really was there at the birth of this new language, the only British artist who could make such a claim. Shortly after the end of the First World War, he went on a trip through the Highlands. The result was a remarkable vision of Scotland not as a tartan anachronism, but as a place of imagination and energy. One particular drawing of clouds over mountains says this with such energy and conviction that we can still learn from it something about ourselves and our home.