CALUM COLVIN OR, GAZES IN THE OLYMPIAN JUNK SHOP

‘Of bodies changed to various forms, I sing’ [Ovid, Metamorphoses 1, i]

‘If we knew, all the gods would awaken . . . despite eternal slumbers, there are eyes that reflect humanities resembling divine and joyous phantoms’ [Guillaume Apollinaire, Young Artists; Picasso the Painter 1905]

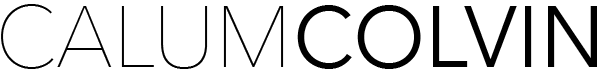

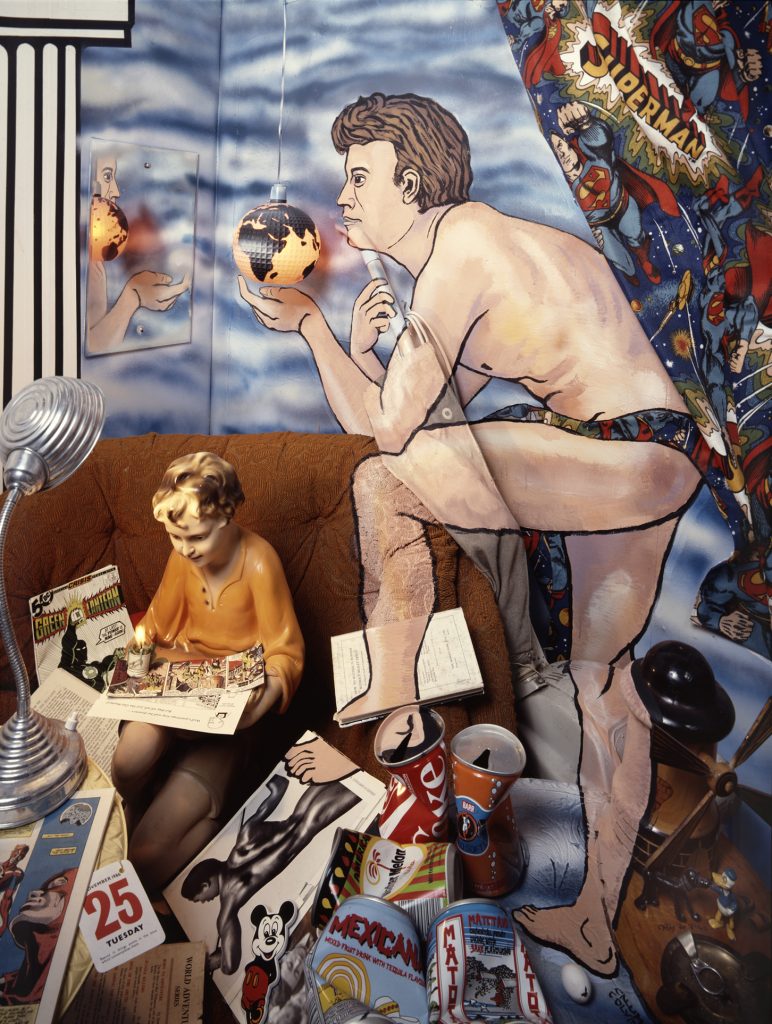

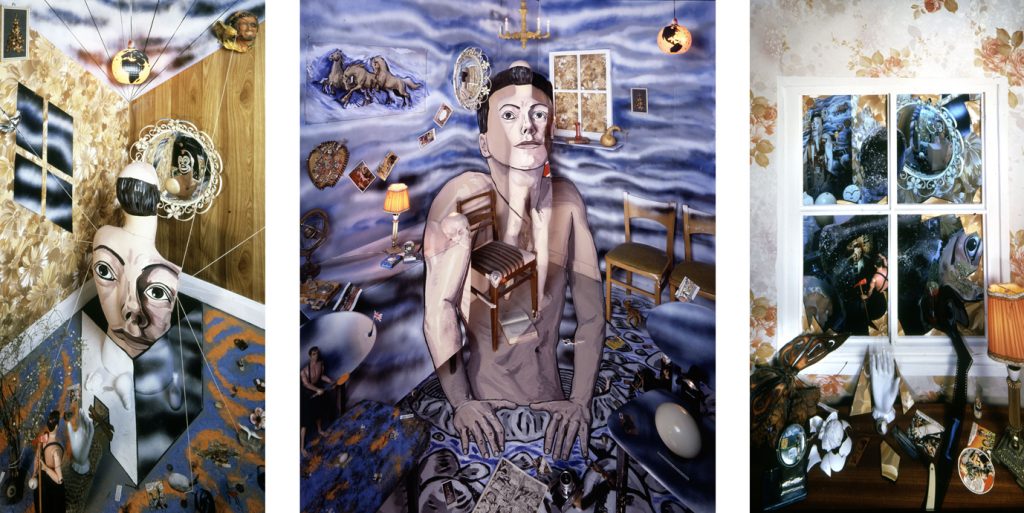

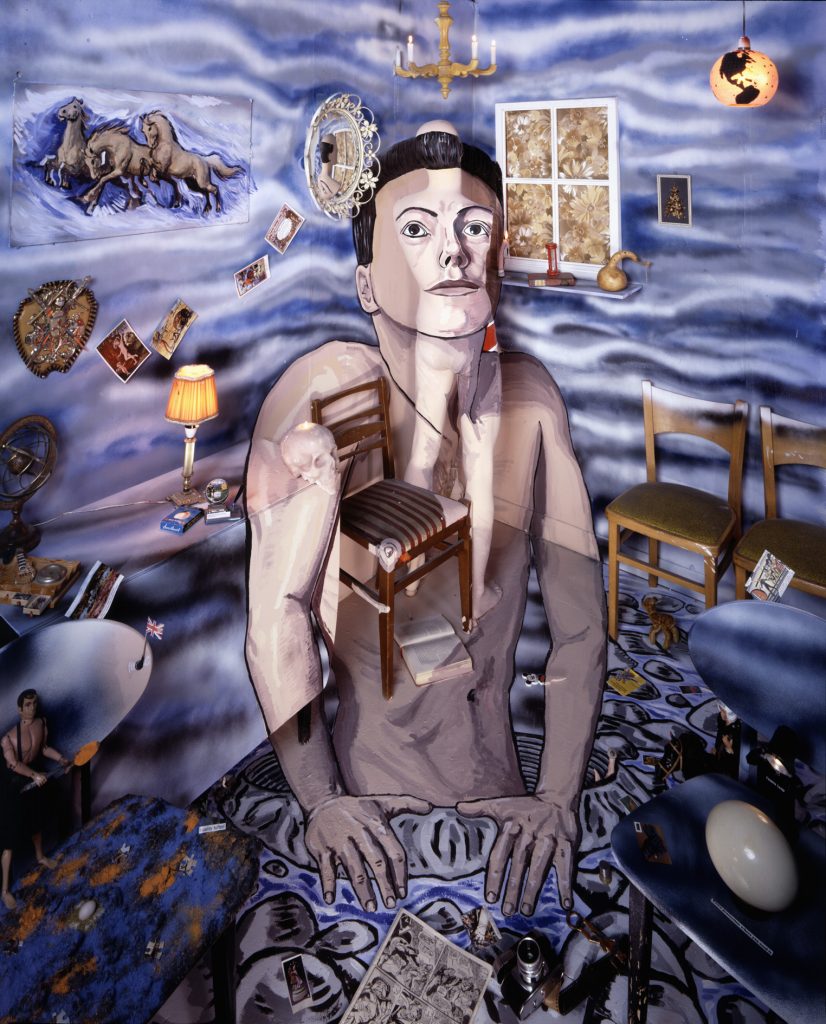

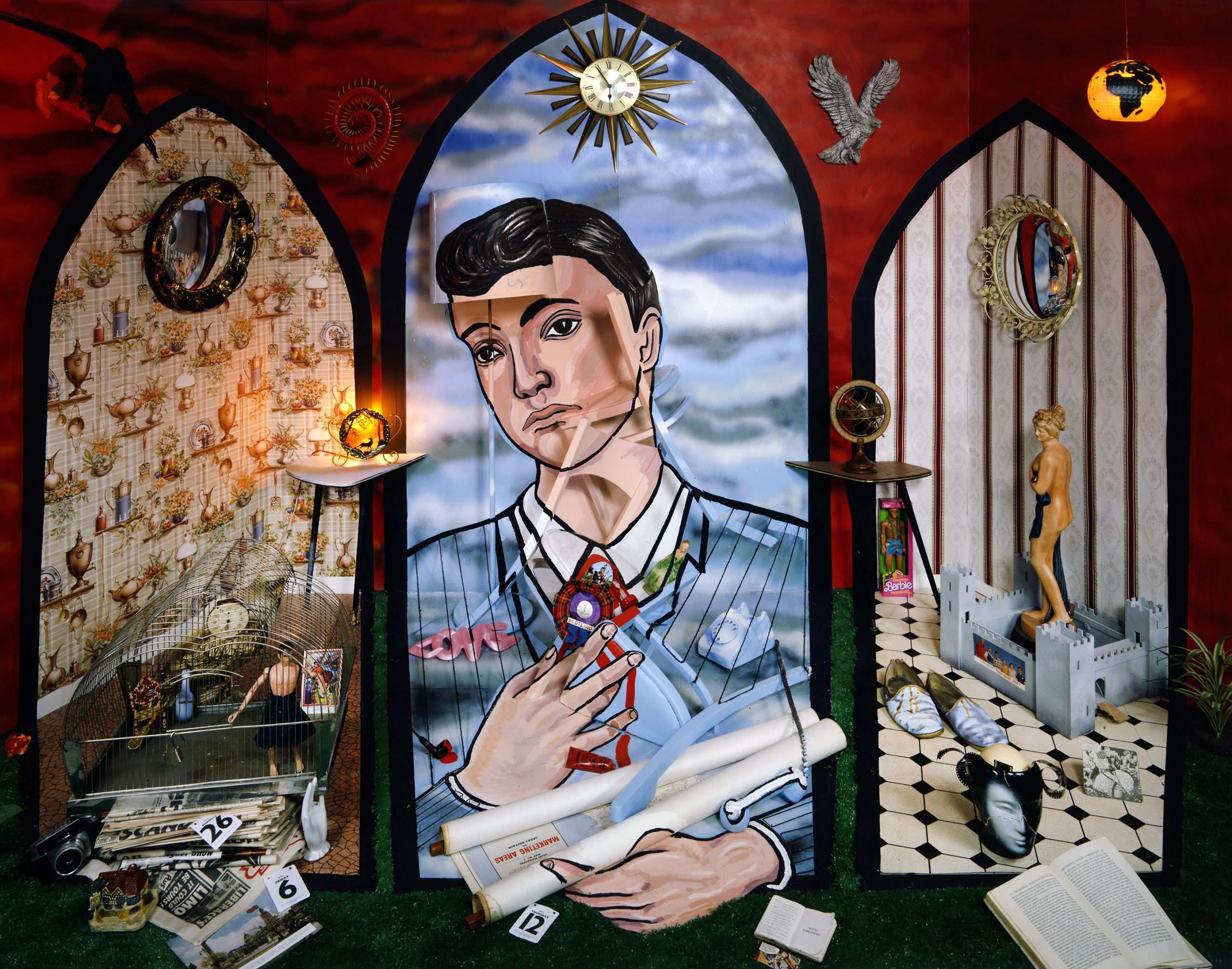

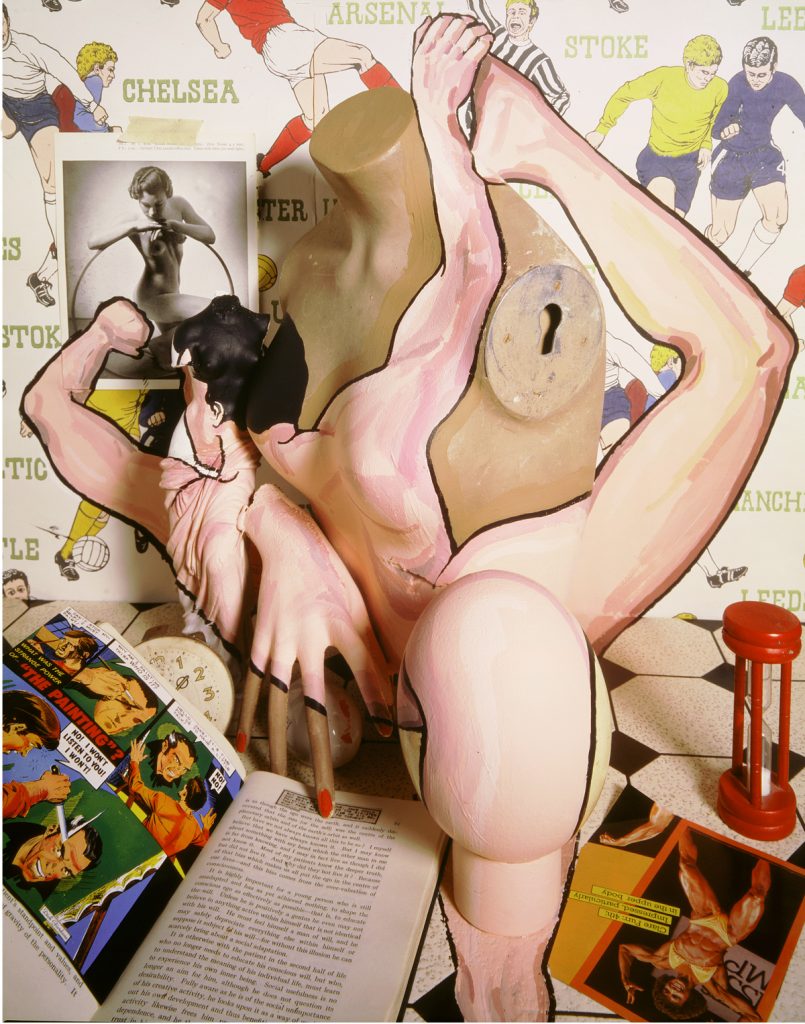

You can see the echoing of the gods and godesses, the heroes and heroines, In Calum Colvin’s audacious pictures. He has bent himself to an invocation of an epic universe, heroically populated, but caught by the webs of the gaze and the opacities of blunt paint, trapped into confined corners with discontinuous, profaned objects. These are the private sites for sight, for Oedipus can still see In his bathroom mirror, in Heroes I. Where the Sphinx should be – Colvin is alluding to Ingres’ painting – a mirror instead asks the riddle; and Oedipus’ response is to dwell on the enigma of his own reflection, a big boy now, but still caught up in his own imaginary image and an omnipotent fantasy as he holds the world – a child’s printed lightshade – in his palm. Or he only appears to: since our displaced view of the mirror deflects this gesture into another blank gaze. Man and boy; the beautiful but unseeing plaster child on the sofa and the composite, domestic, Oedipus made up of a junk shop vacuum cleaner and upholstery. Even when, in all the other cases, Narcissus is not the manifest hero of Colvin’s picture, there still takes place a narcissistic binding of the heroes and heroines to the insecure specular lure of the mirror. (Just as we, the spectators, are bound, fascinated by the seelngness of these photographs). This narcissism ironically echoes their (masculine) ego ideals in the cornucopia of boys comics strewn for us to notice; Superman, the riot police, Dan Dare, the Green Lantern. Where there is – exceptionally – no mirror, as in Heroes II, glass and a frame sets them apart, re-doubling these mythological personages in their role as iterable pictorial quotations. For Colvin’s heroes are endlessly reiterated, mis-en-abyme, across the containing world of his pictures with their mirrors and icon crowded sanctuaries. Not for nothing his selection of the child’s bedroom light-shade which mimics the earth. In the imperious, glaring eyes of his figures; in the recursive metaphors of globes and glassy convexity; in their bulging, whited eye-balls, there is a collecting, containing and radiating of light. They summon sight to see everything echoing in his small worlds.

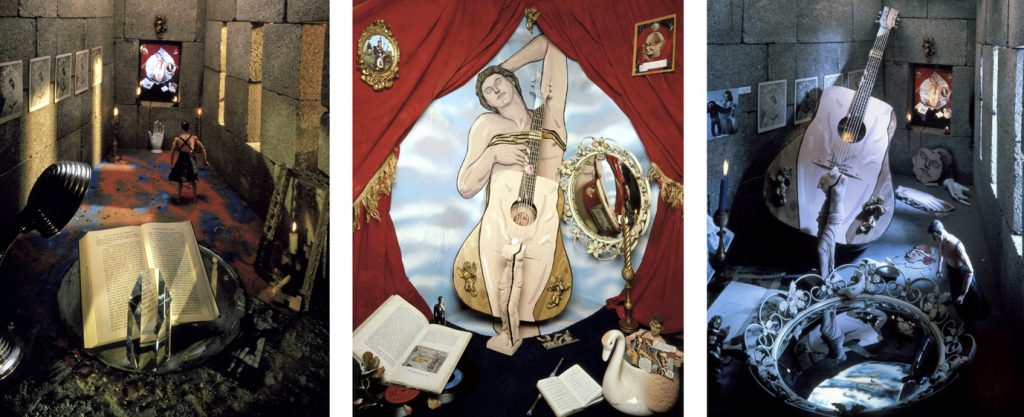

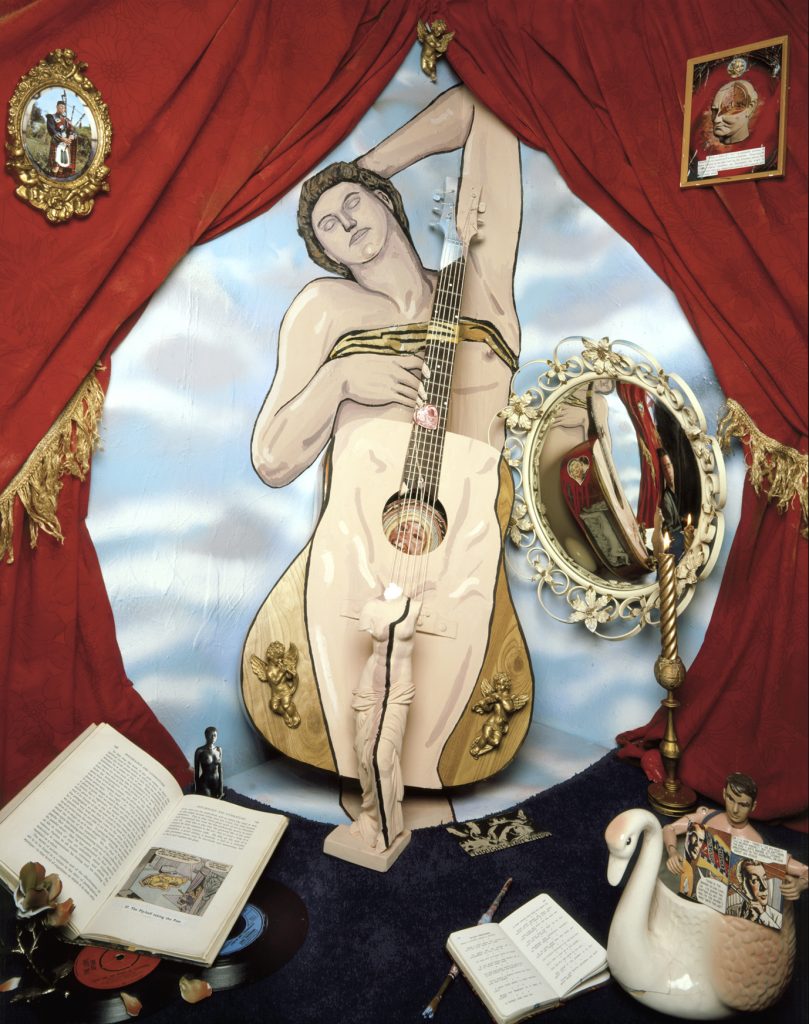

But these machines for the gaze, the fretted mirrors or the goldfish bowls, exact a price – (in an earlier work Colvin showed Atlas staggering under the burden of a world of Images anamorphically perspectlvised into a great transparent orb). It is a mortuarial Venus who is still-born as a dead fragment from the sea of a Woolworth’s mirror in the last act – or, rather, the right hand panel – of Cenotaph. The Vanity of Venus has previously been murderously – gyno-cidally – dismantled by Colvin’s delegated male spectator, a kilted Action-Man with <. pick-axe, in The Death of Venus. That pervasive Western discourse dwelling on the dangers of seeing, drawn on the thematics of vanitas, and rooted finally in the instability of the feminine, disciplined the eye. A toll for peeping. In the first panel of Cenotaph, one of Magnus Hirschfeld’s 1920’s ’sexological’ books on perversion lies open at a case study of a female exhibitionist who possessed a room of crystal. And in front of the book, refracting the page and print, is an erect crystal: thus, visibility of a (narcissistic) body traverses, in its virtual rays, a regulatory and punitive text.

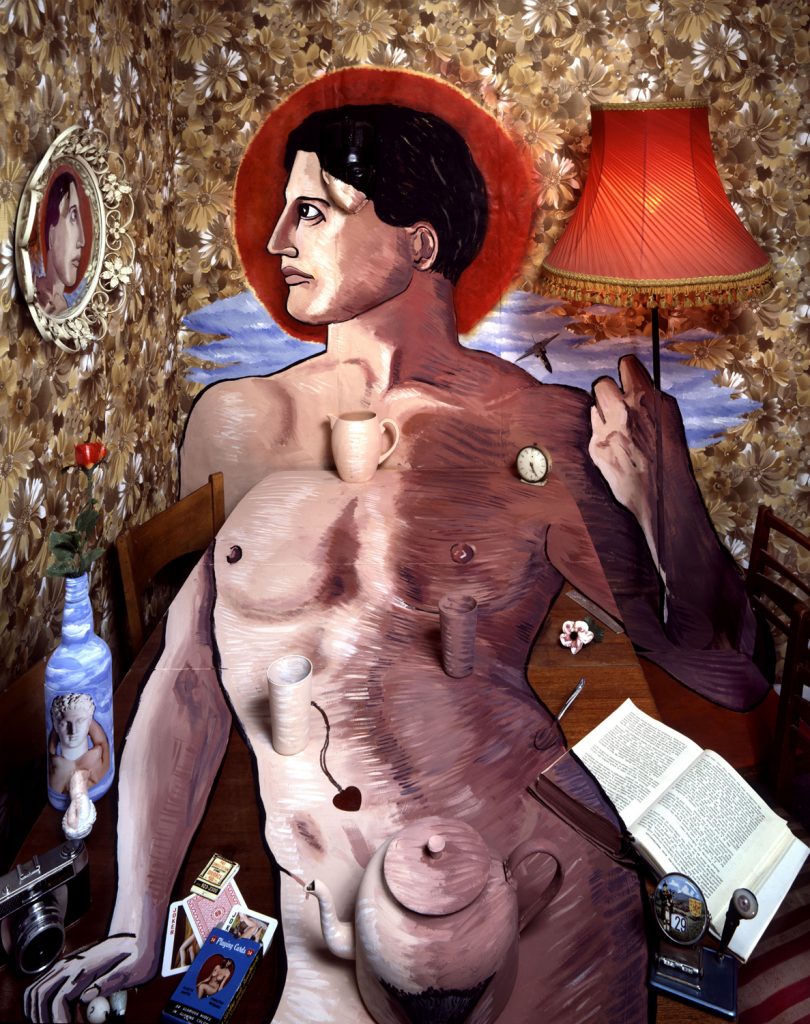

Thus Colvin has built his scenes, his sets, on that exact site where sexual difference intersects with the machinery of seeing. But unlike the vaunted work of Victor Burgin in this same field, Colvin’s photographs have an unpremeditated plenitude, unfettered by academicism, a fullness which is profligate with meanings. There are, too, Colvin’s beginnings in textuality, in a word or words. He will often start his pictures with a proper name, a myth, an encyclopaedia’s definition. Beguiling and anchoring texts to the attentive readers of his photographs are disclosed by the calendar mottos and comic strip texts with which he litters the sets. And then there are other, figural, origins. Promissary – but always, ultimately delusory – points of origin arise in Colvin’s tableaux: in Cenotaph it is the androgynous version of Michelangelo’s Dying Slave, a compound of guitar (metaphoric woman), painted male nude and statuette of Venus. Together they compose a painted being of superimposed genders, set up as a paradoxical altar-piece, a target of looking and itself a blinded and blinding transmitter of the gaze. Cited and re-cited through the triptych, it appears to be reverenced as a mystery (the Hand of Fate stands before it in the left hand panel) and ideal authority by the kilted Action Man (himself a skirted and confused image of masculine power), before its dismembering and miraculous return, still enshrined, in the right hand panel. Surrounded by self-referentiality, Colvin’s heroines and heroes might be conceived of as fantastic versions of self-origination; in the centre panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights a recognisable portrait of Colvin himself arises from the ground, amid the kitsch of the living room, his aspirational face incorporating an androgynous body, the New Adam and the originary body of Eve: the whole a travesty of Adam and Eve emerging into the Garden of Eden, in Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

In Colvin’s vista of sexuality and representation, masculinity shrinks (the little, lost Action Man) in both the Ancient and Modern worlds. It falls under the eye of power belonging to the patriarch, for example to Jupiter, who is significantly absent in Heroes IIand for whose great beard, at the tip of Thetis’ fingers in Ingres painting Jupiter and Thetis, Colvin substitutes a plastic light shade. Yet the gaze of this absent Father, external, (perhaps, even elided and identified with our paramount gaze) sweeps over all these scenes: Oedipus, in Heroes I, has already slain him, only to prepare for his own blindness. Colvin has his patriarchs too, to contend with, in spite of apparently springing, fully armed from the dining room carpet. That is, he has his fathers in art to match: – Donatello, Michelangelo, Ingres and Bill Woodrow. The grand melancholia of Cenotaph as well as the malevolence of Incubus clearly indicate a register of portentous, anxious sublimity; an interlacing of banal consumer domesticity and its debris with the profundity of super-sensible agencies. This is Colvin’s terrain; we might properly style it Mock-Heroic; here Bathos performs as a strategy, framing a visual rhetoric which could negotiate Colvin’s belated place in art; his secondariness to his own elected, paternal heroes of art. The Mock-Heroic could (and, in fact does) trope this, coping with his status as an epigoni, and engaging his high and strong ambition to produce – in his words – ‘Epic pictures’.

Nevertheless, a threatening otherness invests his versions of Classical and Christian iconography, (he has just begun work on a Temptation of St Anthony). The wished for unity of body and ideal image discovered in the look of the mirror stage is fractured and dispersed by Colvin. It is continually deferred, shifted away into the maze of duplicitous repetitions, like the disordered dream of those rediscovered but mis-arranged portraits of Colvin that are glimpsed through the window of the right hand panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights: a scene presided over by the ominous Hand of Fate, once again. The Ovidian echoes of endlessly metamorphosing bodies are countermanded by the capricious breaks on the surfaces of those same bodies through the wayward topologies of his furniture. The prior, venerated, continuities of the Michelangelo figure in Incubus are riven by disruptions – allegorised by the sub-pictures of riot and civil disorder – as it is painted across the edges of a child’s rocking horse, chairs and plinth. But, given the history of 20th century assemblage, Colvin has remembered and managed to re-embody it; spanning the aggregate of these remnant bits and suturing the breaks in the body of things. The black outlines of his drawn and painted Ideal body – seen correctly only from the god’s eye of the view camera’s point-of-view, that sharp end of the gaze – flow and bizarrely contradict this fallen world that they now find themselves in the midst of. Meanwhile Colvin strives for the Epic, and also, perhaps, for a particular fantasmic structure which has haunted British art since at least the early 18th century. This is the elusive ‘Grand style* of a Classical tradition; which we, the spectators, peep at across the chasms of consumer detritus in his pictures. Yet, like other Europeans before; – Offenbach, De Chirico, Stephen McKenna among them – he has probably succeeded in the project of re-awakening the gods to a modernised life.

University of Sussex

3rd October 1988

‘The Turkish Bath’ 1986

‘Heroes II’ 1986

‘Heroes I’ 1986

‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ 1987

‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ (Centre panel)

‘Narcissus’ 1987

‘Incubus’ 1988

‘Cenotaph’ 1987

‘Monument for Bank’ 1988

‘Male Nude’ 1988