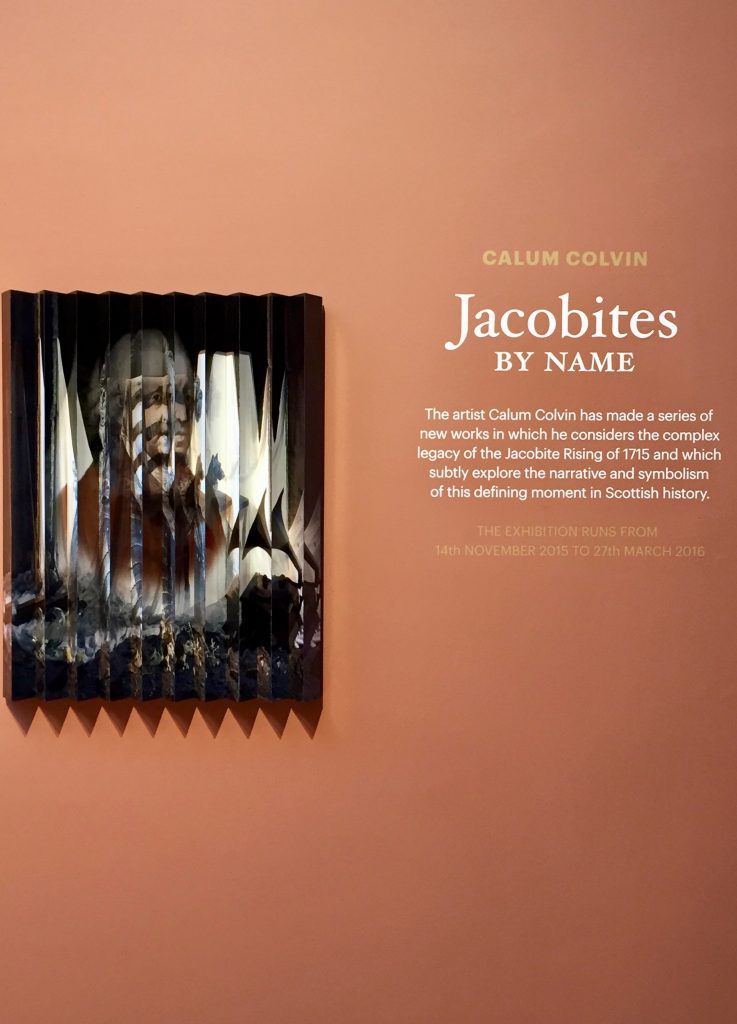

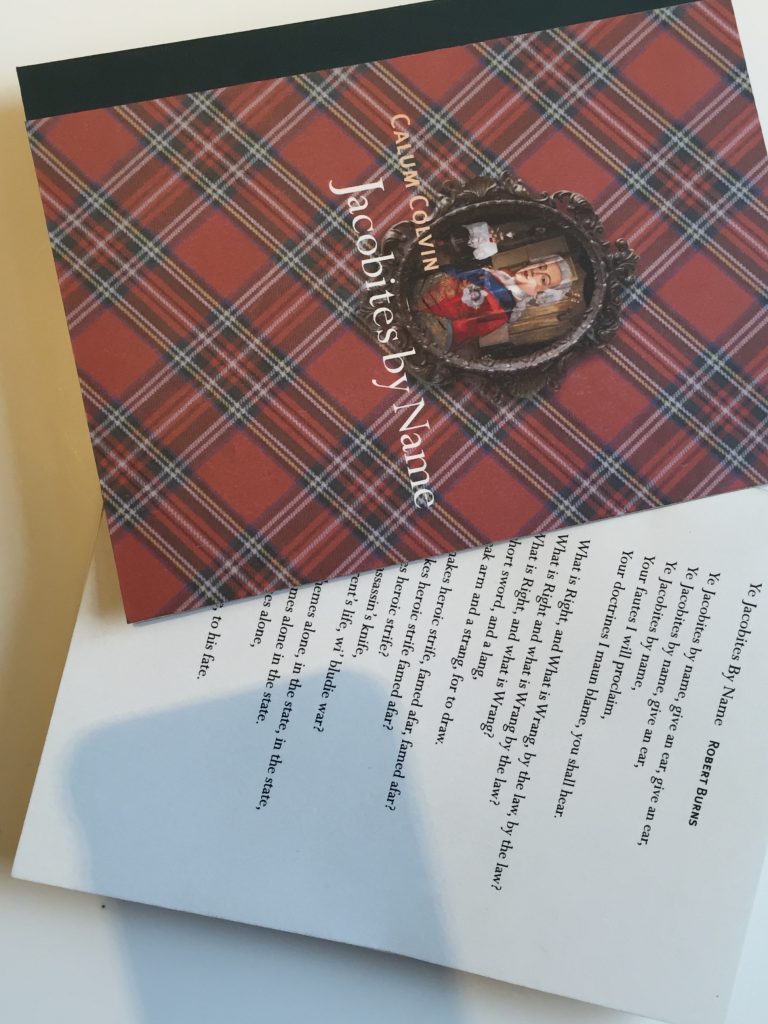

A guide to the works as displayed in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery 14/11/15 – 28/3/16 exhibition/intervention Jacobites by Name, which was installed within the permanent display Imagining Power: The Visual Culture of the Jacobite Cause in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh.

Introducing Jacobites by Name

It all begins with a monument. You may think that you are entering the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, but here are Canova’s graceful angels, weeping over the memorial to the Royal House of Stuart in Rome. It’s quite enough to divert attention from the grand frieze above, where Charles Edward Stuart takes his place between Cameron of Lochiel, Flora Macdonald and Cluny Macpherson on the golden Scottish walk of fame. The memorial is both here, and not here: it is taking us to Rome, and back again almost at once. For the angels are framing the pale, carved door of a classical tomb, but as we move closer and further away again, looking from different angles, the door ceases to seem shut for ever, and something begins to emerge within. This is a portal into the past, into other times and places, and even as we remain in our own, there is a glimpse of things half hidden, half-forgotten, and yet uncannily present. The door leads, counter-intuitively, upstairs to a room on the first floor, where Calum Colvin’s artworks have been installed among the portraits in the Jacobite collection.

‘Jacobites by Name’ issues invitations to centuries past and reminders of the here and now, through huge digital photographs framed in antique gold, an anamorphic cylinder complete with latin legend or the newly engraved glass hidden in the display case of translucent Jacobite treasures. These spectacular responses to the Stuart portraits reflect and refract, mirror, mimic and multiply images that have been preserved so long and so respectfully that we almost cease to see their original meaning. The startling intervention in the Jacobite Gallery brings new colour into familiar features, as well as stealing the attention in its own right.

Colvin’s beautiful, contemporary artworks are reflections of and on older representations of power, hope, fear, courage, loss, loyalty, and leadership, which deepen in meaning as they shift between then and now, observer and observed. The bright-eyed, red-lipped Bonny Prince, looks eagerly out of a dark oval border, all ready for the spotlight and quite untroubled by the image in the far corner of the gallery, of an immaculately groomed military commander morphing into a troubled old man. There is a seat in each of these images, but it is never occupied by the Royal Stuart. Who is the subject, after all, when it comes to portraying royalty?

Charles Edward Stuart dominates the show, but at every turn those who represented him in their own particular way are being remembered too. National Portrait Galleries traditionally attract many visitors whose primary interest is in the celebrity sitters rather than the artists, but Colvin’s incorporation of eighteenth-century prints and paintings directs attention to little known artists such as Wassdail, William Mossman and Hugh Douglas Hamilton. Easels, brushes and empty frames mix among the books and antlers, candles and ‘Anonymous’ masks, ironising the anonymity of the artist.

The silhouetted gramophone in the ‘Lochaber no More’ sequence, or Colvin’s signature image of a guitar resting on a chair in the portrait of ‘Betty Burke’ also remind us of the crucial parts played by Scottish songwriters in creating the romantic legacy of the Stuarts. The musical strain is amplified by giving some of the artworks song titles and calling the entire show, ‘Jacobites by Name’. Colvin’s creative interactions with Burns have helped to open new ways of approaching the enduring and endlessly controversial presence of Jacobite memories in modern Scotland. Burns’s well known song, ‘Ye Jacobites by Name’, echoes internally all around the gallery, though the teasing removal of the pronoun, ‘Ye’, collapses the customary distance between the speaker and those addressed. The song lyrics, whether understood as the voice of one of Charles Edward Stuart’s opponents or defeated followers, are at once keeping alive the memory of the Risings and lamenting the human cost.

Charles Edward Stuart was not merely represented on paper, canvas and music: the Jacobite leaders executed after Culloden were standing in for their Prince, as he escaped through the Highlands and Islands. Colvin’s portrait of Balmerino, who went to his death calmly proclaiming unswerving loyalty to King James, is one the most arresting of all. The ghostly engraving hovers over two wooden boxes, which suggest the executioner’s block even as they serve as a stand for an ironing board, draped with tartan cloth. The iron stands to attention, as if for preparing the plaid for battle, but it is all unplugged and the cloth may now serve only to cover a table, or act as the prisoner’s blindfold. Perhaps it stands for the ironies of history. And yet, how truly can any of us see those who seem to be lighting up the darkness? This show is far too thoughtful to offer answers, but it brilliantly raises question after question.

Fiona Stafford

From the publication Jacobites by Name, an artist’s book with contributions from Professor Fiona Stafford, Kathleen Jamie, Rab Wilson, James Lawson, Professor Calum Colvin and National Galleries of Scotland Senior Curator Julie Lawson. 86 pages 6,574 words. Edition of 100. ISBN 978-1-906270-99-5. Published by the Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland.

Exhibition captions by Julie Lawson, Senior Curator, Scottish National Portrait Gallery:

(plaster replica), with lenticular print intervention by Calum Colvin

Canova’s original marble monument, which was completed in 1819 in in St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome.

The Latin inscription means:

To James III, son of James II, King of Great Britain,

to Charles Edward, and to Henry, Cardinal… sons of James III, the last of the Royal House of Stuart

The quotation below is from the Book of Revelation: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord

The figures portrayed are those of James Edward Stuart (on the left), his elder son Charles Edward (on the right) and his younger son Henry Benedict, Cardinal of York (centre) who, upon the death of his brother, took the title of Henry IX.

The monument is surmounted by the escutcheon of the Stuarts, with two lions rampant.

Colvin’s intervention in the monument to the Stuarts is a meditation on the theme of waiting. The Stuart ‘Pretenders’ spent most of their lives in exile in various European courts, planning their return to claim the throne that they and their Jacobite sympathisers believed was theirs by right, both legal and divine.

The sequence of images evoked in the lenticular print suggest their destiny: dust sheets thrown over furnishings in cold, empty palaces evoke the melancholy of exile; a sequence of hands signify birth, marriage and succession; the closed door denotes the final outcome of the Risings of 1715 and 1745 and the hopes and aspirations of the Jacobites turned to dust.

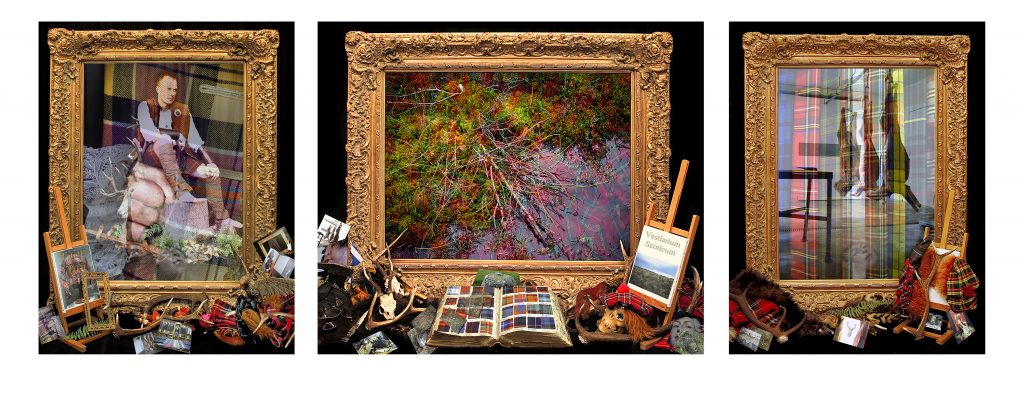

Unpacking the myth of Scotland’s history, Colvin’s central image in a series of photomontages was produced in an experiment with digital cameras for the BBC production ‘A Digital Picture of Britain’ (BBC4, 2005). The framed large image shows a section of the boggy field of Culloden, somewhere between the Jacobite and Hanoverian lines. A bolt of Stewart tartan fades into the bog, suggesting the early origin of tartan in fabric dyes obtained from the land. The multiple layers of images that extend from the centre composition allude to the gradual classifying and dubious codification of clan tartans during the Victorian ‘Balmoralisation’ of highland culture in the 19th century. A foil to this theme emerges with further contemplation of the detail, which alludes to the tragic human consequences of these historical and cultural shifts. Hanging venison in the right hand image evokes the slaughter of the ‘rebels’ by ‘Butcher’ Cumberland and his Hanoverian troops after the battle of Culloden and the clenched fist emerging from the delicate lace cuff on the left suggests the coercion ordinary highlanders underwent to participate in the rising.

The title refers to The Vestiarium Scoticum by John Sobieski Stuart that was first published by William Tait of Edinburgh in a limited edition in 1842. John Telfer Dunbar in his seminal work, History of Highland Dress, referred to it as “probably the most controversial costume book ever written.” The book itself is purported to be a reproduction with color illustrations of an ancient manuscript belonging to Charles Edward Stuart on the clan tartans of Scottish families. Shortly after its publication it was denounced as a forgery and the “Stuart” brothers were also denounced as impostors for claiming to be the grandsons of Bonnie Prince Charlie.

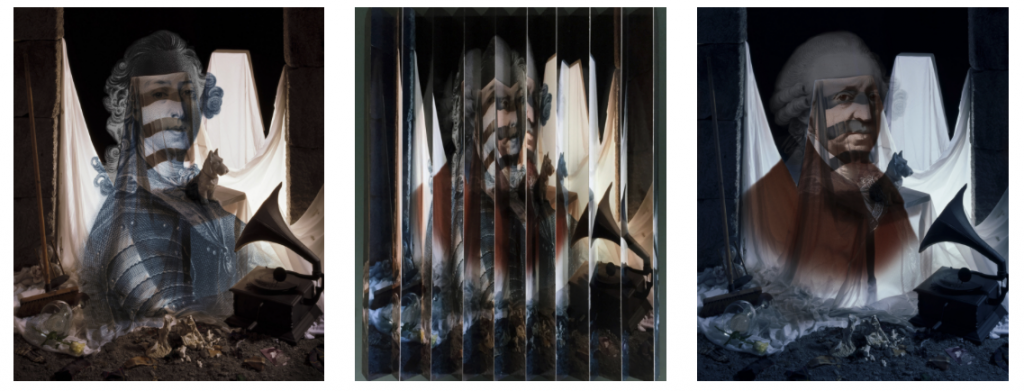

Lochaber No More I, Anamorphosis, Lochaber No More II, 2015

This series of images was inspired by the anamorphic portrait Anamorphosis, called Mary, Queen of Scots, 1542 – 1587 painting (or turning picture), which is in the collection of the National Galleries of Scotland. The viewer is initially confronted by a distorted perspective caused by two images painted on alternate sides of vertical strips. Deviating from the original painting of a young woman (thought to be Mary, Queen of Scots) and a skull, this portrait series of her last ancestor potrays Charles Edward Stuart as a young man based on an engraving by Johann Georg Wille of 1748 (after Louis Tocqué), and the other of the prince in old age and infirmity, based on the portrait by Hugh Douglas Hamilton painted in about 1785. Both portraits are printed over a photograph of a constructed stage evoking a landscape of carved stone blocks and furniture covered with dust sheets. The image reflects on the passage of time and the melancholy of lost Jacobite hope. Colvin has based the image of Charles Edward Stuart in old age on the portrait of him by Hugh Douglas Hamilton painted in Rome in 1775. Fragments of burned tartan hint at the tragic outcome of the last Highland Rising. The gramophone suggests the sad melody Lochaber No More that was said to move the aged prince to tears whenever he heard it. The quality of light in the image evokes Jacobite glassware. The work also alludes to the tradition of secret symbolism and optical illusionism in Jacobite art.

Throughout his intervention in this gallery Colvin repeats images of Charles Edward, changing them subtly until they consist of a series of signs and symbols out of which the viewer constructs a likeness of the prince.

The profile portrait of the James Edward Stuart is based upon the portrait by Louis Gabriel Blanchet in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. In contrast to the imposing image of James in the painting, wearing armour and full of martial resolve, Colvin presents us with a fragile, semi-transparent figure in an insubstantial world of crystal and ice that could at any moment shatter and melt away. The landscape reminds us that most of James Edward’s life was spent in exile, geographically remote from Scotland (he had lived for only a few weeks on his native soil before his parents’ 1688 exile led them to seek refuge with James II’s first cousin, Louis XIV of France). The warming pan that makes up part of the barometer on the wall refers to the popular rumour that James was not the son of James II and VII, but had been substituted in infancy for a still-born prince. The Jacobite imagery of the blackbird (a nickname for the Old Pretender and symbolic guardian of the three kingdoms), and the moth (drawn to the light, ie Restoration) appear as details. The heap of ‘vendetta’ masks may refer to those followers who abandoned their leader in 1715 when it did not serve their own interests to remain loyal to the Jacobite cause. The title of the work is one of the nicknames given to the ‘Old Pretender’.

Arthur Elphinstone, Sixth Lord Balemerino, took part in the Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1745. Captured after the battle of Culloden, he was executed at Tower Hill in London in August 1746. He refused to plea for mercy, declaring in his speech from the scaffold: ‘If I had a thousand lives I would lay them all down in the same cause’. Balmerino went to his death dressed in full regimental uniform and wearing a plaid cap to signify his loyalty to the Jacobite cause. A popular song of the time, however, contains the lines:

Brave Balmerrony… in the midst of all his foes

Claps Tartan on his eyes…

A Scots Man I livd…

A Scots Man now I die…

May all the Scots my footsteps trace…

By giving Balmerino the tartan blindfold of romantic myth, Colvin reminds us how historical events are subtly altered in the re-telling and embroidered by the popular imagination. The gradual symbolic association of tartan garb with Stuart loyalty is thus taken to its final conclusion with the act of patriot martyrdom – the ‘Jacobite Theatre of Death’ [Daniel Szechi] and led to the eventual “Abolition and proscription of the highland dress” under the Disarming Act of 1746.

John Erskine, 6th Earl of Mar (1675-1732)

digital photograph after the engraving by John Smith after Sir Godfrey Kneller.

Portrait of Charles Edward Stuart (after Liotard) or Young Pretender, 2015

Colvin has made a series of images of Charles Edward Stuart, based on numerous prototypes. In Young Pretender, based on the portrait after Liotard that hangs in the gallery, the figure of the prince is painted onto an arrangement of objects including a chair, a guitar and an easel. The chair may refer to the throne that he tried to restore to his father. The guitar signifies the importance of Jacobite song as a subversive weapon. Because there were no physical artefacts involved, there was no ‘evidence’ of disloyalty on the part of singers of Charlie’s awa or Will ye no come back again and Ye Jacobites by Name. The easel refers to the way in which the likeness of the Prince was copied and reproduced, subtly altered and then eventually appeared on whisky bottles and shortbread tins as

a cipher for ‘brand Scotland’ and the popular imagery

of sentimental Jacobitism.

Portrait of Charles Edward Stuart (after Mosman) 2015

Colvin has based this image of the prince on the portrait by William Mosman which is, in turn, based

on a portrait by Louis Gabriel Blanchet of the nineteen-year old as a warrior prince wearing armour. In his version, Mosman substituted the armour with the Stuart tartan, blue bonnet and white cockade worn

by Charles Edward on his entry to Edinburgh in 1745.

Colvin’s prince is painted onto a set consisting of a chair (referring to the throne – the seat of power), a guitar (referring to Jacobite song) and a canvas on an easel. The accoutrements of an artist’s studio – easel, canvas, brushes and palette – refer to the proliferation of portraits of Charles Edward, copies of copies becoming further and further removed from the authentic original. Some portraits traditionally thought to be Charles Edward are actually of his brother Henry Benedict. Others seem to be a hybrid of both princes, resembling both but accurately depicting neither.

Harlequin 2015

Colvin’s schematic portrait refers to the crude depictions of the outlawed Charles Edward Stuart in mass-produced prints. His tartan costume was misrepresented or simplified, perhaps because it was based on a verbal description, resulting in an almost clown-like figure and known as a ‘harlequin’ portrait. The title refers to the costume of coloured patches worn by the comic character of Harlequin in the Commedia dell’arte. Colvin points with irony to how ineffectual the print would have been as an aid to

the detection and capture of the fugitive prince.

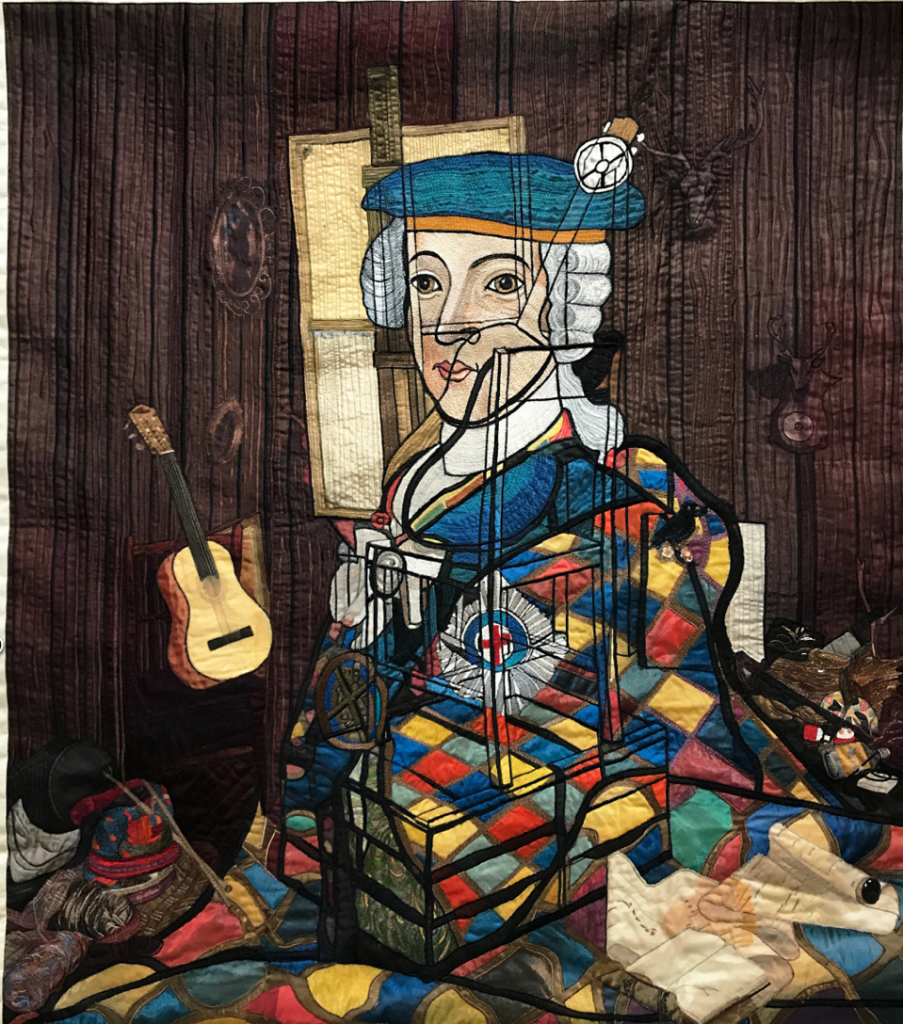

Harlequin Embroidery (after Calum Colvin). Elma Colvin

Embroidered print, made by Elma Colvin in 2017

This is a hand-stitched digital print by the artist’s late mother, based on the popular print depicting Charles Edward Stuart known as The Harlequin. This large-scale version was included in the exhibition ‘Museography’ in the McManus Galleries, Dundee in 2017. A smaller version was included in the original exhibition in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery (see below) alongside Hidden Portrait, a wooden box with digital photograph inside.

.

This schematic portrait of Charles Edward Stuart is based on The Highlander Portrait by Robert Strange.

Seditious Glass 2015

Opaque twist wine glass with laser etched artwork. The Latin motto engraved on the glass reads: TEMPORA MUTANTUR NOS ET MUTAMUR IN ILLIS which translated means ‘Times change, and we change with them’.

Secret Portrait, 2015

Anamorphosis, made in 2015. An anamorphosis is an intentionally distorted image that, when reflected in a cylindrical mirror, becomes legible. Colvin has based this on the anamorphic portrait of Charles Edward Stuart of about 1745 in the collection of the West Highland Museum in Fort William, Scotland.

Lenticular digital photograph (printed with the ability to move through image sequence when viewed from different angles).

The title of this work contains the ambiguity that is to be found throughout Colvin’s intervention. ‘Pretender’ is one of the names by which James Edward Stuart, ‘The Old Pretender’, and his elder son, Charles Edward, ‘The Young Pretender’ are known. The original meaning of the word was ‘claimant’. They claimed to be the rightful heirs to the throne in accordance with the laws of primogeniture. However the word ‘pretence’ has come to denote falsehood or deceit.

The portrait of Charles Edward Stuart is superimposed upon the landscape of Culloden Moor. His image gradually disappears and is replaced by a white horse, symbol of the Hanoverians. The final scene of desolation denotes the cruel aftermath of the battle

of Culloden: the sword has rusted; the white rose,

an emblem of the Jacobites, is dead; the battle is lost.

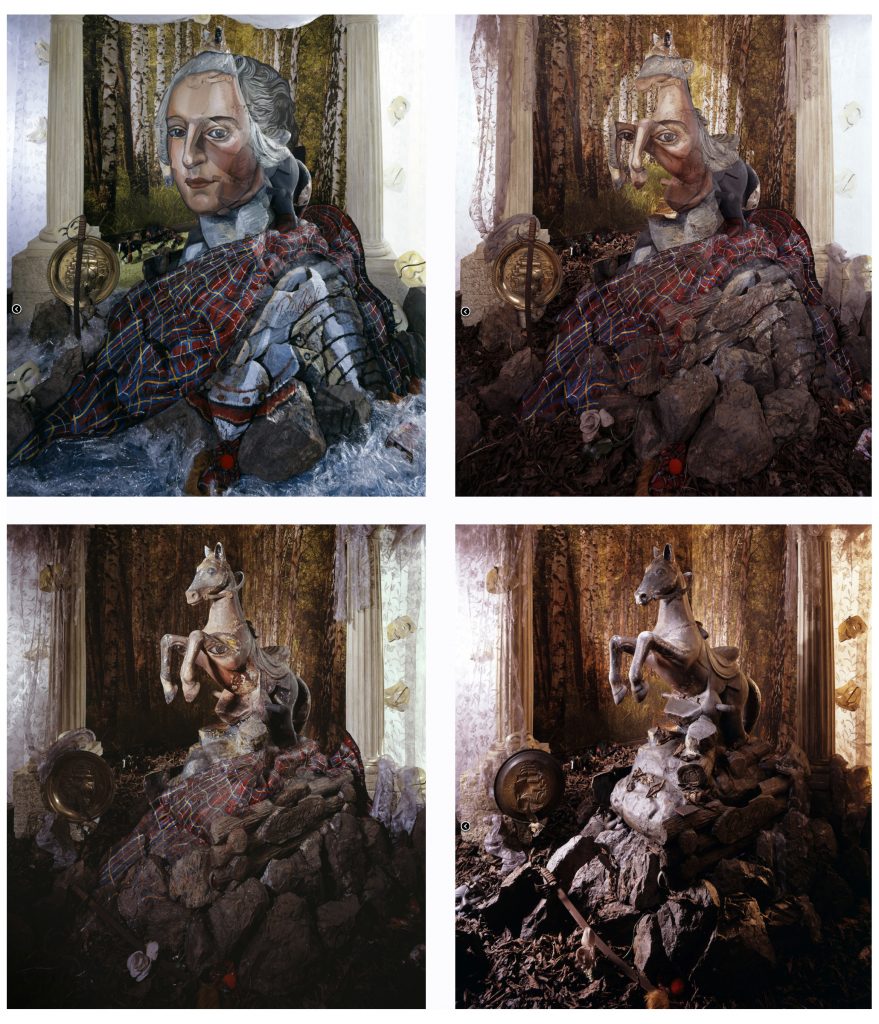

Pretender I-IV, 2014

The title of this work contains the ambiguity that is to be found throughout Colvin’s intervention. ‘Pretender’ is one of the names by which James Edward Stuart, ‘The Old Pretender’, and his elder son, Charles Edward, ‘The Young Pretender’ are known. The original meaning of the word was ‘claimant’. They claimed to be the rightful heirs to the throne in accordance with the laws of primogeniture. However the word ‘pretence’ has come to denote falsehood or deceit. The use of masks throughout Colvin’s work is an ironic reference to this double meaning.

The portrait of Charles Edward Stuart is superimposed upon the landscape of Culloden Moor. His image gradually disappears and is replaced by a white horse, symbol of the Hanoverians. The final scene of desolation denotes the cruel aftermath of the battle

of Culloden: the sword has rusted; the white rose, an emblem of the Jacobites, is dead; the battle is lost.

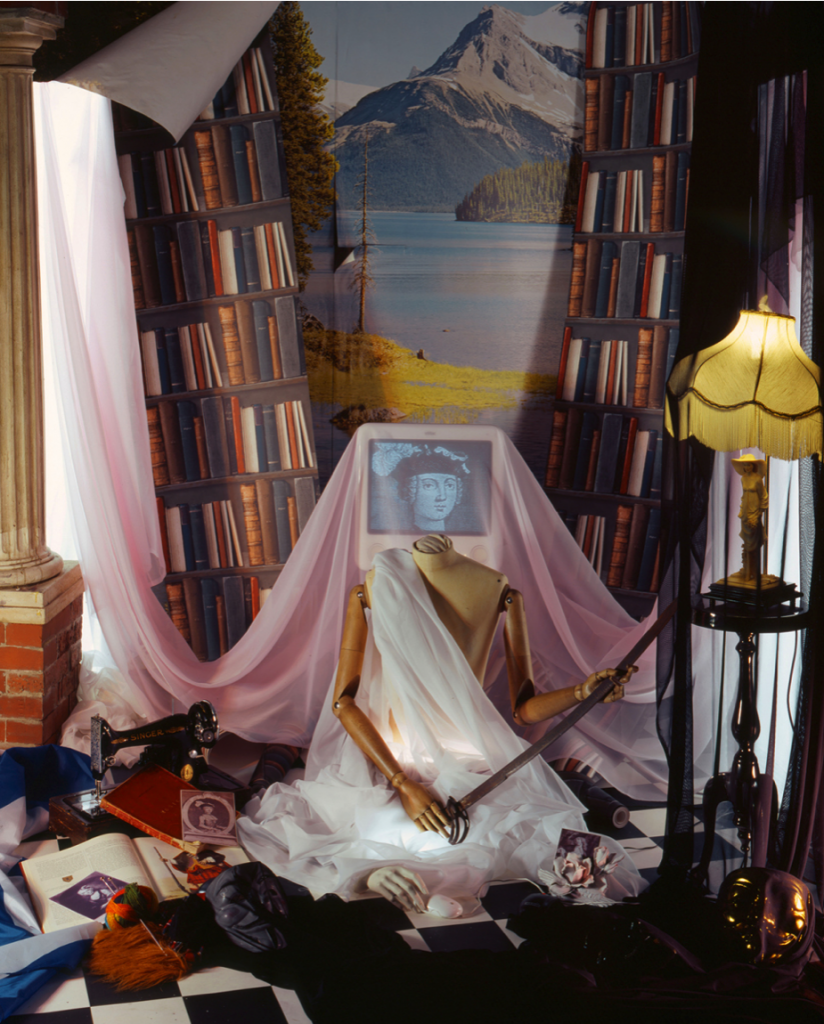

Betty Burke – a digital forgery, 2015

The propaganda print depicting Charles Edward Stuart disguised as Flora Macdonald’s Irish maid during his flight after Culloden may have been originally intended to ridicule the prince as cowardly and effeminate. It was a common slur to imply that the Celts were not ‘manly’ because of a tendency to emotional excess and melancholy. Colvin points to the irony inherent in the image, which, if intended to traduce the prince, has the opposite effect: rather,

it endows him with a noble beauty and delicacy. Its ambivalence might even be taken to signify the dual nature of one who, according to the precept of ‘Divine Right’, would become, as anointed king, both human and divine.

Jenny Cameron, 2015

This image dwells on the uncertainty surrounding the legend of this Jacobite heroine. She may or may not have been the daughter of Cameron of Glendessart, who may or may not have become the mistress of Charles Edward Stuart, and who, disguised as a man, fought at Culloden. According to one version of the story, a milliner from Edinburgh, also called Jenny Cameron, was mistaken by the Duke of Cumberland for ‘Miss Cameron, the Young Pretenders Diana’ and imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle.

There were hundreds of prints made in her image in many guises, portraying her as a female Bonnie Prince Charlie, a sword-wielding soldier and a wanton hussy! Her notoriety was such that an anti-Jacobite Commedia dell’arte was performed at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane in 1746 entitled ‘Harlequin Incendiary or Colombine Cameron’ where the traditional roles of Harlequin and his mistress, were replaced with The Pretender and his ‘bold amazon of the north’.

She is said to have followed Charles into exile and later returned to Scotland penniless. In Chambers ‘Traditions of Edinburgh’ 1825, in a footnote in his second volume the author says, ‘Jeanie Cameron, the mistress of Prince Charles Edward … was seen by an old acquaintance of ours standing upon the streets of Edinburgh, about the year eighty-six. She was dressed in men’s clothes, and had a wooden leg. This celebrated and once attractive beauty, whose charms and Amazonian gallantry had captivated a prince, afterwards died in a stair-foot somewhere in the Canongate.’

Colvin’s Jenny Cameron is headless: she could be anyone. Her ‘portrait’ from a contemporary engraving is visible on a computer screen behind a veil. The computer mouse emerging from under her skirts is the means by which her image will be manipulated, controlled and disseminated. Surrounded by emblems of femininity and domesticity, she wields a sword. Cameron represents not only sexual ambivalence

but defiance of convention.

The Jacobite Theatre of Death 2015

Jacobites by Name, an artist’s book with contributions from Professor Fiona Stafford, Kathleen Jamie, Rab Wilson, James Lawson, Professor Calum Colvin and National Galleries of Scotland Senior Curator Julie Lawson. 86 pages 6,574 words. Edition of 100.

ISBN 978-1-906270-99-5.

Published by the Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland.

Calum Colvin: The Stuarts

James Lawson

When we talk about perspective in pictures, we are usually thinking of ourselves as distanced –standing back, taking in the larger view. Calum Colvin’s method of picture-making seems, at first, to depend utterly on the fact of vision being remote from its object and –consistent with picture-making since the invention of the one-point perspective construction in the fifteenth century– chaining us to the rock of fixed viewpoint.

Colvin’s practice is complicated. It is to set up in his studio a large plate-camera and a stage-set. He places a transparency in the frame of the camera. Looking at the stage-set through the back of the camera, he sees a superimposition of image (the transparency) and object (the props assembled within the stage-set). He then paints the props at those places where the image has seemed to strike. It is a matter of moving back and forth between what he sees from the perspective of the camera and his stage-set. There is a paradox at the centre of the procedure for, instead of a picture plane, his paint-surface is three-dimensional. At last, he replaces the transparency with a sheet of film and takes a photograph.

The final picture is of the unique coincidence of object and projection. The observer is aware of the fixity of perspective imposed upon him/her by the procedure; the sensation is of a sort of imprisonment. At the same time, however, he has the visual data to enable him, imaginatively, to abandon his point of view, to conceive the stage set from different positions, to mark the unaccountable lines and colours that, it seems, randomly bespatter the scene and to retrieve objects from image. As possessor of his eye, the observer is fixed to the spot. As a mobile observer in his interpretive imagination, however, he finds the image exploded and material integrity returned to the stage-set.

Colvin makes us puzzle about perception. Our initial conception of his work is of space and surface in a Cubistic sort of confusion. His medium is assuredly photography. But no less is it painting and installation. The puzzle is complicated further by the recent addition of another medium, with digital manipulation added to his means of image-making.

Whilst, then, the image is of a fixed state of things and the observer starts off with its perspective, in practice, he is denied certainty and is unfixed in space. In that condition, he is left free to exercise the multitude of faculties by which we make our navigations of the world.

Even the eye resists the point-perspective that has generated the picture. To observe a work by Colvin is to find oneself abandoning that connoisseur’s pose –easy to spoof– standing back, profile raised, taking in the whole, and adopting instead the hunched myopia of the expert or the childishly curious –getting close-in. In contradiction of the rooted spot, Colvin offers a world of copiousness. The principle of assembly of the copious is aggregation –a sort of entropy not quite reversed. The observer feels called upon to bring order, or at least find connections among the apparent detritus within the scene. The activity feels forensic. Holmes would survey the scene, now taking in all, now fetching from his pocket his magnifying glass. No detail escapes him. We, who are slower, will live long with a work by Colvin, in the hope of catching up.

The present show, Jacobites by Name, is an important one. It consists of a series of interventions, in the Jacobite Gallery of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, through which the artist presents a rich meditation upon Scotland, her history and her myths. It appears therefore appropriately at the Scottish institution. And it is doubly appropriate for the venue, for it is a serious and illuminating meditation upon the portrait itself. The institution is offered an enriching example of how it might understand the genre that it is its role to represent to the public.

To begin with, Colvin has built a stage-set. In the corner of the studio is a podium. On it, a chair is ready, covered by a dust sheet, for the arrival of the portrait-sitter. Or else the work has been done, and the place has been returned to its shrouded dust-gathering. At the back of the space the back of a canvas faces us. There either is a portrait painted or there is not. In addition, and opening up another possibility, is the guitar that rests on the chair. We’re in the corner of the pub, and the folk-musician will begin or has finished an Old Song.

Colvin has made a number of works using the set and projecting upon it a number of portraits held by the National Galleries. Charles Edward Stuart is the subject, the sitter and the protagonist. On any occasion the scene can include different props, different detritus. It becomes explicitly the artist’s studio in one instance, where the apparatus of the painter appears (and included for his inspiration is a picture of a specimen of a butterfly –which we shall find ourselves looking out for elsewhere in the exhibition). Where the young Charles Edward had been half-seen and half-imagined –Cherubino avant la lettre– an ornament to any lady’s salon, the textures and colours of the cream-tea that has been delivered to the studio prepares the scene, and the projection of the portrait (by William Mosman) takes place. The painter is at work on the other side of the canvas, only his bare feet visible. When the sitter does, as-it-were, turn up (when the transparency of Johann Georg Wille’s engraving of Charles Edward in armour, of 1748, is put in the back of the camera), a scottie-dog in plaster is set on the chair pointed intently at an old wind-up gramophone. There’ll be no changing of the record in this re-marketing of HMV and re-presenting of Millais’ theme –for Jacobite Jocks. The same dog will be attentive to the same gramophone when the engraving is replaced by Hugh Douglas Hamilton’s portrait of Charles Edward as an old man.

Because of the palimpsestical nature of Colvin’s final pictures, there is a quality of transparency to their content. Presences are ghostly. The portraits, transformed by Colvin’s process, take on an air which we realise they always possess and which by a switch of the mind becomes manifest –their spectral air. No matter how animated the portrait, the sitter is dead –ever there, like an incubus, ready to be called forth.

As the sitter is dead, so his narrative spools back behind a layering of veils. And the final act turns to smoke all that has gone before. So it is of Charles Edward, youth of promise –the painters tell us– warrior, romantic escapee, site of hopes betrayed by longevity. We see youth juxtaposed with age in the corrugated double portrait, the one visible on one 45-degree viewing angle, the other on the other.[Lochaber No More, using Wille’s engraving and Hamilton’s painting] It is the tersest of biographies. But Colvin out-does himself in a four-stage image of Charles Edward of remarkable thematic and narrative richness.

The man that we have is present in the mind in complex and ambiguous form. He is here before us in Colvin’s quadruple portrait that, by means of lenticular technology, shifts through time as we move across the picture plane. [Pretender] The image is also presented in its component parts.[Pretender I-IV] An armoured Charles Edward now sports a plaid.

A new stage has been set up for this occasion, this epic. At the back of the space is a lacy-curtained window. Two classical columns frame the hero. The stage is occupied by a pile of rocks from which rises a rocking-horse –or rather, a rearing toy horse. A multitude of ancillary material is included. Here is the triumphant campaign and its desolate conclusion. At first, Charles Edward’s portrait dominates the scene. Toy soldiers are marshalled in tight formation. By stages, the set breaks forward through the projected picture-plane, and the features of the Pretender, first disrupted, are at length abraded by the scene, which itself changes to one of disorder. Finally, the horse is riderless and the repute of the hero is at the mercy of the victors, the Pretender at last nothing more than the word engraved on the side of the toy-horse, ‘Rebel’. The view through the window is now of Culloden Wood. A brass repoussoir disc with galleons in sail is turned to concavity. Scarcely to be made out, there survive some fragments of the curtain and a few of its embroidered butterflies.

The scene is shifting. So is the physical, and the intellectual perspective. The exhibition –or, we should remind ourselves, the intervention, for the holdings of the SNPG in the Jacobite Gallery participate in the work– becomes a most acute meditation upon the portrait itself. Charles Edward’s likeness is a particularly telling instance of the portrait acting cameleon-like with regard to whom it purports to represent. The various likenesses of Charles Edward –connected to his fame or else to his notoriety– comprise a portrait supplied by the man who lent his features, created variously by the various artists, made problematic by the conflict of Jacobitism and Hanoverianism, sentimentalised in accordance with the Scottish vice.

In Charles Edward, Colvin has chosen an intriguing case. The romantic narrative has it that he is most famous for his disguise. It was mumming as Flora Macdonald’s maid, Betty Burke, that he escaped the battlefield at Culloden, crossed the country and threw it off at last, escaping eventually to Italy and the protection of Protestantism’s old enemy. The hedge-betting that had seen him named after the Catholic martyr and a successor of the Hammer of the Scots was done with. On the other hand, disguise could be effected by the painter or draughtsman. Charles Edward was depicted on many occasions by illustrators working, as Chinese Whispers do, from copies and from copies of copies. They could, equally, superimpose their own ignorance or confusion. Charles Edward was on one occasion turned into Harlequin by an anonymous artist who perhaps misconstrued another artist’s muddled understanding of tartan garb.[G. Will after Wassdail]

His likeness was to be hidden from the enemy by conspiratorial Jacobites. At the same time, it was to be revealed among the like-minded. Colvin documents those evasions and disclosures. He has created miniatures of his own representations of Charles Edward, to be hidden under snuff-box lids and in suchlike places. An original example has been lent by Inverness Museum and Art Gallery. At the same time, again, Charles Edward has a material currency in tat –recreated as a minute embroidery of Colvin’s version of the Harlequin portrait, or printed on a plate. At this point, the image is of the character of a cult-object, and the interest in it quasi-religious. The same can be said for its later manifestation on the proverbial shortbread tin. [It’s Walker’s Shortbread.]

The most spectacular of the works that hide Charles Edward’s likeness in the exhibition is an anamorphic version of the cream-cake picture. It is stretched into the shape of a donut and is laid on a table, like a Ouija board. Examples of such images survive from the 18th century. They were surely for the entertainment of gatherings of conspirators or ex-conspirators. The picture would be brought out, a polished silver drinking vessel would be set at the donut’s centre, and the diners or topers could see reflected in the cylindrical mirror –for that was what the vessel was in effect– the image of the Prince over the Water. All 360 degrees of Colvin’s stage-set can be seen in reflection. It is a most remarkable sensation to find oneself in the centre of Colvin’s room!

Of course, the painted portraits in the care of the National Portrait Gallery play no such games. They are public works, or at any rate works that do not fear to be seen. The armoured man does not hide. The man in his finery and displaying his honours is no recluse. The habitué of the salon is at ease. These are performances of life, and the portrait, generally, is the representation of the person in his or her role. It need not be a starring one, though here it is. The truth might be known to his manservant. If the painter can be received in the sitter’s privy chamber, neither party nor yet the public are usually much interested. The pictures that Colvin has used tell of history, not psychology.

It can seem that Colvin is exposing the falsehood or the impossibility of the portrait. Not so. What he tells us, with such clarity within such myriad complexity, is that what we see is just what he makes in his photographic tableaux, projections, intersections of dimensions –likeness, rhetoric, deception, even evasion. The portrait tells all these truths and untruths. An untruth revealed and a truth accepted as such are the products of observation and research. Criticism and history draw truth from anything, for they exercise every effort not to be gulled. Colvin’s work originates in irony –art’s challenge to its observer to seek truth behind surfaces.

Around the anamorphic image and engraved on a glass is the motto:

TEMPORA MUTANTUR ET MUTAMUR IN ILLIS

(Times change, and we change with them)

From the publication Jacobites by Name, an artist’s book with contributions from Professor Fiona Stafford, Kathleen Jamie, Rab Wilson, James Lawson, Professor Calum Colvin and National Galleries of Scotland Senior Curator Julie Lawson. 86 pages 6,574 words. Edition of 100. ISBN 978-1-906270-99-5. Published by the Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland.