A miscellany of contextual information on the images and related ruminations.

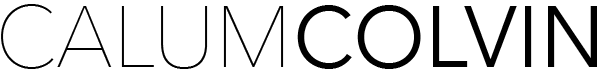

Dirt and Deity

This work entitled ‘Dirt & Deity’ is based on a Silhouette, or shade by John Miers, cut in 1787 when the poet was 35 years old. These were made by using candlelight to cast a shadow of the sitter onto oiled paper and the outline drawn in pencil, which would then be transferred to paper and shaded in black.

In this instance I wanted to make this shade a much more elusive mix in it form as a visual image reflecting the shadows of darkness that haunted his personal life. The silhouette in this instance contains objects that might serve to memorialise Burns – a scythe, a mouse, a plough, throwing shadows within a shadow. A further projection is imposed on the fringes of the picture – Ossian and Coila, Burns’ source of inspiration and Muse, as originally depicted by John Leighton in the National Burns.

The title is lifted from Lord Byron’s journal entry for December 13th, 1813, upon reading some of Burns’ letters.

They are full of oaths and obscene songs. What an antithetical mind!—tenderness, roughness—delicacy, coarseness—sentiment, sensuality—soaring and grovelling, dirt and deity—all mixed up in that one compound of inspired clay!

Negative Sublime I and II

These two portraits of Burns and Lord Byron, entitled Negative Sublime I and II, are transposed upon a table and a chair, a bookstand, and some books. Upon closer inspection, the two paintings are different but it becomes apparent they are painted upon the same setting. They reflect back on each other, looking in opposite directions, different vistas but the same viewpoint, two polar opposites. I wanted to contrast these two poets, from diametrically opposite social standings, although these two also have much in common- not least an undertone of scandal and transgression.

Brought up in Aberdeen by his Scottish mother, Byron once described himself as “half a Scot by birth and bred a whole one” and is alleged to have spoken with a distinct Scottish accent all his days. However he is assumed here, through the symbols in the picture, as a quintessentially English poet. I was also drawn to this pairing by Byron’s journal entry for December 13th, 1813, upon reading some of Burns’ letters:

They are full of oaths and obscene songs. What an antithetical mind!—tenderness, roughness—delicacy, coarseness—sentiment, sensuality—soaring and grovelling, dirt and deity—all mixed up in that one compound of inspired clay!

Burnsomania

There are many poems by Burns to choose from – too many to really pick a favourite. However one particular poem I would highlight is Burns epic, Ossianic poem ‘The Vision’ from 1786, where the labour weary poet encounters his muse Coila one evening, and reflects on his calling as a bard, poverty, and his place in history. On the verge of quitting poetry forever, this metaphorical vision of Ayrshire and Scotland reinvigorates his poetic genius. Far too long to reproduce here, a few verses give an idea:

There, lanely by the ingle-cheek,

I sat and ey’d the spewing reek,

That fill’d, wi’ hoast-provoking smeek,

The auld clay biggin;

An’ heard the restless rattons squeak

About the riggin.

All in this mottie, misty clime,

I backward mus’d on wasted time,

How I had spent my youthfu’ prime,

An’ done nae thing,

But stringing blethers up in rhyme,

For fools to sing.

Had I to guid advice but harkit,

I might, by this, hae led a market,

Or strutted in a bank and clarkit

My cash-account;

While here, half-mad, half-fed, half-sarkit.

Is a’ th’ amount.

…………….

Down flow’d her robe, a tartan sheen,

Till half a leg was scrimply seen;

An’ such a leg! my bonie Jean

Could only peer it;

Sae straught, sae taper, tight an’ clean-

Nane else came near it.

Her mantle large, of greenish hue,

My gazing wonder chiefly drew:

Deep lights and shades, bold-mingling, threw

A lustre grand;

And seem’d, to my astonish’d view,

A well-known land.

…………..

“And wear thou this”-she solemn said,

And bound the holly round my head:

The polish’d leaves and berries red

Did rustling play;

And, like a passing thought, she fled

In light away.

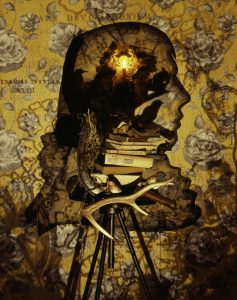

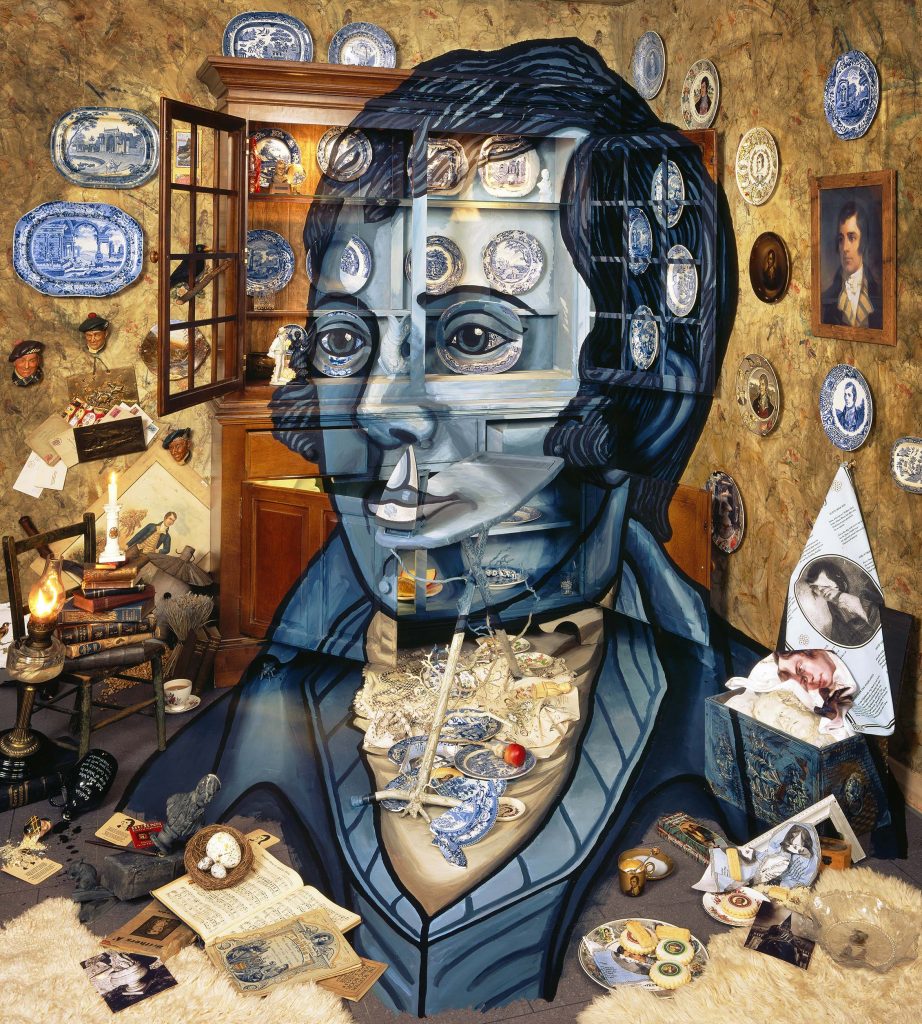

The work ‘Burnsomania’ considers the unprecedented growth in popularity of “the heaven-taught ploughman” in the years following his death. The term ’Burnomania’ was coined in 1811, by the Rev. William Peebles in the book titled Burnomania; the celebrity of Robert Burns considered in a Discourse addressed to all real Christians of every Denomination, where Peebles accused Burns of being an ‘irreligious profligate’ who wrote ‘vile scraps of indecent ribaldry’.

Despite his undoubted infamy, we still celebrate Burns in innumerable reproductions of his likeness on everything from whisky bottles to stamps, from biscuits to beermats. My pluralisation of the title celebrates this myriad recycling of the immortal brand!

Twa Dogs

Whilst engaged on the development of the series of images entitled ‘Ossian Fragments of Ancient Poetry’, I was researching the various strands and connections between Robert Burns and Ossian (the fact/fictional 3rd Century Celtic bard), I came across the reference in the poem ‘Twa Dogs’ to Cuchullin’s dog Luath in ‘Fingal’:

The tither was a ploughman’s collie

A rhyming, ranting, raving billie,

Wha for his friend an’ comrade had him,

And in freak had Luath ca’d him,

After some dog in Highland Sang,

Was made lang syne,

Lord knows how lang.

Whilst re-reading this poem, it occurred to me I could re-interpret this dialogue between two dogs, one ‘o’ high degree’ and the other ‘a ploughman’s collie’, as a meditation on contemporary dualities in Scottish society.

Football in Scotland is symptomatic of the ongoing conflicts of identity that exist in Scottish life; especially since the influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland began in the middle of the nineteenth century. The most obvious example of this is the phenomena of Rangers versus Celtic, a century-old rivalry that has been fueled by the mutual animosity between Glasgow’s Catholic and Protestant communities. Celtic was founded in 1888, with the original intent of raising money for food and clothing for poor Irish Catholic immigrants in Glasgow’s East End. It soon developed into a rival for Rangers, which was founded in 1873 and had a strong affiliation with Unionism and Protestantism.

I wanted to make each dog not only representative of Rangers and Celtic-Catholic and Protestant, I also wanted to highlight the phenomenon of commodified tribalism – the incongruous aspect of attributing such emotional attachments to corporate companies. Hence the head of each dog is made from training shoes, one Nike one Adidas.

The record in the right hand corner is ‘Scotland’s Own Tartan Lads’ (The Alexander Brothers) to represent the opposing football fans – Celtic waving their Irish tricolours and Rangers with their Union Jack and England flags – united in their Scottishness. The framed photo in the centre is a double symbolic figurehead for each persuasion, King Billy and the Pope.

Dialectic oppositions abound in this picture, as well as a number of puns (‘Gales’ honey, the ‘fan’). A darker undertone of terrorism is hinted at with the inclusion of ‘Scotch on the Rocks’ a 70’s novel of Scottish nationalist terrorism, but it is worth remembering that a situation such as found in Ulster didn’t happen in Scotland – the Twa Dogs still inhabit the same hearth.

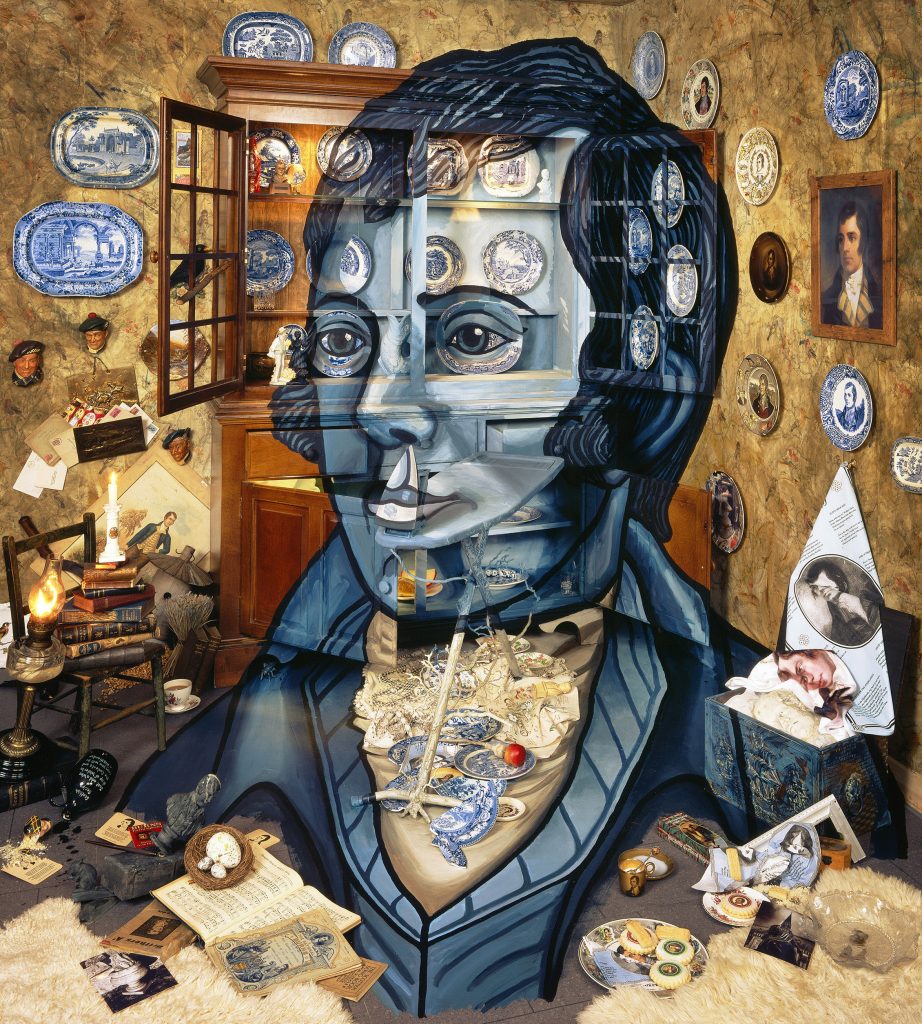

Twa Plack

The work of the same title is based on the ‘Twa Plack’ label/stamp produced in 1959 by the Scottish Secretariat (a radical organisation founded in 1926) as part of an unsuccessful campaign to persuade the Postmaster General to issue a commemorative stamp to mark the bicentennial year of Burns’ birth (a stamp was finally issued in 1966). They were frequently placed (illegally) next to the official postage stamp and thus postmarked, but more often than not stuck on lamp-posts, walls and the windows of Glasgow tram cars.

A plack was a small copper coin, the sixtieth part of a pound Scots (ie two-thirds of an English penny), and although the coin itself had long since ceased to circulate since the time of Burns, the expression was still current in many popular sayings, and, indeed, it figures in Burns poems to signify a trifling sum.

My version, fifty years later, hints at financial turmoil and devalued currencies in a time of less clear-cut political opposition. Particular relevance for the Scottish Independence Referendum lies in Burns’s Bruce inspired call to action Now’s the day, an’ now’s the hour and UK Chancellor George Osborne’s notorious sermon on the pound.

Portrait of Robert Burns (after Skirving)

This image is based on Archibald Skirving’s iconic and idealized drawing of Burns from 1796, in itself a kind of construction. I was considering two aspects of Scottish culture within this body of work—the invented, and the native. I was thinking of Burns as an aspect of the native, the heaven-taught ploughman. So, here in a detail in the left corner he is presented as if a Pict, an aboriginal if you like—although in fact I have montaged the facial tattoos from a painting of a Maori chief onto his face. The invented aspect is evoked in a further detail emerging from the shoulder on the right hand side, by a Bossons figurine—a music hall Scotsman complete with tam o’ shanter bunnet.

The creative act of reinvention is alluded to in this work and it hints at the reductive aspects of fame. In the foreground, there is a shattered Elvis mirror, and here is a mallet, with the word Worldwide written on it, a reference to the Masonic Order and its world of secret symbolism (Burns was inducted into the order in 1781).

On the shelf there are three books. This is the idea of the three R’s —reading, writing and arithmetic—three volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. So, this implies the idea of the autodidact, as they say, the lad o’ pairts. There is the suggestion of the hearth but, of course, it’s a bookshelf, with three books laid out like a reading room—suggesting the Scottish Enlightenment ideal of elevation through education.

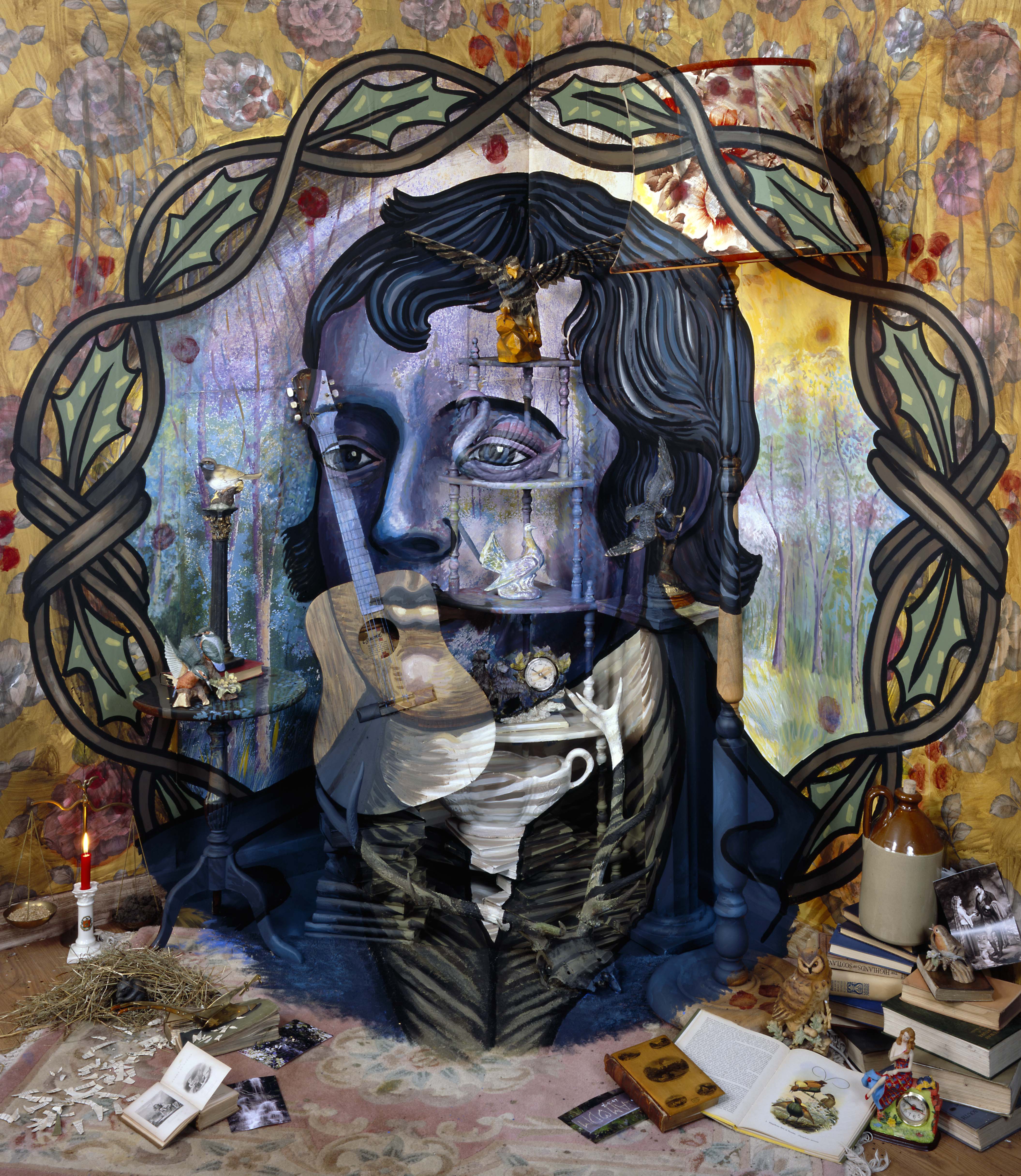

Burns Country

This work unites two separate cultural phenomena: the album Elvis Country * and the geographical and cultural landscape of Burns, the rural idylls you see engraved in Burns editions, a landscape, principally Ayrshire and the lands the rustic bard once worked. This was a starting point for the background structure of the picture, both familiar and exotic, rich and poor. Burns appears of his time and his people, but an exotic oddity singled out by his extraordinary gift—his woodnotes wild as his coat of arms declaims, referencing Milton’s L’Allegro (1645). The holly wreath framing Burn’s likeness evokes the wreath with which his ‘Scottish Muse’, Coila crowns him in his epic poem The Vision (1786).

*Elvis Country (I’m 10,000 Years Old) was first released in 1971. However records only stretch back 258 years from then, when one Andrew Presley exchanged marriage vows with Elspeth Leg in the parish church of Lonmay in Aberdeenshire. Their tenth son, also Andrew, was born around 1720 and emigrated to North Carolina in 1745. Further links can be made between Presley and Burns: impoverished youth, extraordinary early fame, carefully nurtured public image and early death. Elvis visited Ayrshire briefly on March 3, 1960 at Prestwick, although he never left the airport.

Portrait of Colin McLuckie

The Portrait of Colin McLuckie is a powerful and evocative vision of human fortitude. McLuckie was a kenspeckle figure from Colvin’s youth. A retired miner, victim of the curse of pneumoconiosis, he would nevertheless recite the works of Robert Burns by heart. Set inside a rough wooden shed, the subject is painted as a head and shoulders rising from the detritus of his outhouse site. The tools of a miner’s labour are scattered to right and left: a pickaxe, hammer, brush and Davy Lamp. Interspersed with these emblems are various publications of the works of Robert Burns and memorabilia relating to the poet. The two central props are a short step ladder and a distressed wheelbarrow, upright and leaning against the wall. It is across these objects that the figure of McLuckie is painted. He is in old age, he appears feverish and fragile, and is dressed in a tartan dressing gown with pyjamas. But, he also appears to be in the process of an oration. He is both recalling the lyric and rhythm of Burns’ poetry and experiencing the ecstasy of recitation. The rusted and broken shards of the wheelbarrow’s floor describe the mouth of the orator and his fractured voice.

Burnsomania

Colvin’s Burnsomania gives a kaleidoscopic review of the ways in which the nation has celebrated Robert Burns. In the corner of his studio Colvin has created a set that is decorated with a display cabinet, with chairs, with various rugs and lamps, and even an ironing-board complete with the iron. Around this furniture, he has arrayed every kind of Burns-inspired knick- knack and gee-gaw: commemorative plates, prints, books, table-cloths, cups and goblets, statuettes and Burns-club certificates. On the wall to the right there is a print modelled on Alexander Nasmyth’s portrait of the poet from 1787. It is this portrait that Colvin has used for his overpainting of the set with his expressive image of the Bard.The photograph is a celebration of Burns and what he has come to represent in Scottish, and world, culture. Colvin’s work highlights the ‘mania’ for Burns, but recognises this as a colourful and positive energy; even in its ‘kitsch’ manifestations.