’The Two Ways of Life’ was an international touring exhibition of seven large scale photographic artworks exploring and re-interpreting the iconography of the 1857 allegorical photomontage ‘The Two Ways of Life’ by O.J. Rejlander. First shown at the Art Institute of Chicago, the work toured to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Nickle Arts Museum, Calgary; Winnipeg Art Gallery; Karlsruhe; Stockholm and Helsinki. Exhibition catalogues with essays by David Alan Mellor and Colin Westerbeck, ‘The Two Ways of Life’ 1991, and‘The Two Ways of Life and Other Photographic Works’, Dr. Andreas Vowinckel, Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe 1993. Works in collection of Ferens Museum Hull.

The Two Ways of Life was one of the most ambitious and controversial photographs of the nineteenth century. The picture is an elaborate allegory of the choice between vice and virtue, represented by a bearded sage leading two young men from the countryside onto the stage of life. The rebellious youth at left rushes eagerly toward the dissolute pleasures of lust, gambling, and idleness; his wiser counterpart chooses the righteous path of religion, marriage, and good works. Because it would have been impossible to capture a scene of such extravagant complexity in a single exposure, Rejlander photographed each model and background section separately, yielding more than thirty negatives, which he meticulously combined into a single large print.

A catalogue was published in conjunction with the exhibition held at the Art Institute of Chicago, May 4-Sept. 15, 1991.Text: Colin Westerbeck, David Alan Mellor.

Below is the text of the catalogue, written by David Alan Mellor, accompanied by the images.

The Two Ways of Life by David Alan Mellor, May 1991

Calum Colvin’s The Two Ways of Life is a recent addition – but a perverse one – to a long series modernising that commonplace of Renaissance iconography, The Choice of Hercules. Like O.G.Rejlander’s version of this topic in 1857, Colvin has assembled a vast multi-part photographic tableau. But while in those previous handlings by Hogarth and Rejlander there was a confirmation of high moral seriousness and of Virtue against Vice, Colvin has thought otherwise. Instead he has upset the moral fixities of Industry and Idleness, of Virtue and Vice by way of a turbulent narrative, an amphigouri. a sea of nonsense across which a fantastic voyage is undertaken by the manniken toy-hero of his previous photo-tableaux. The Ship of Fools, the Narrenschif, is the carnival,metaphor by which Colvin satirises his chosen framework of Humanist idealism. This ship sets sail in the first picture in the Two Ways of Life suite, The Empty Universe, and

it then journeys on through all the other panels, by way of the moral geography of rocks and grottoes and wrecks .

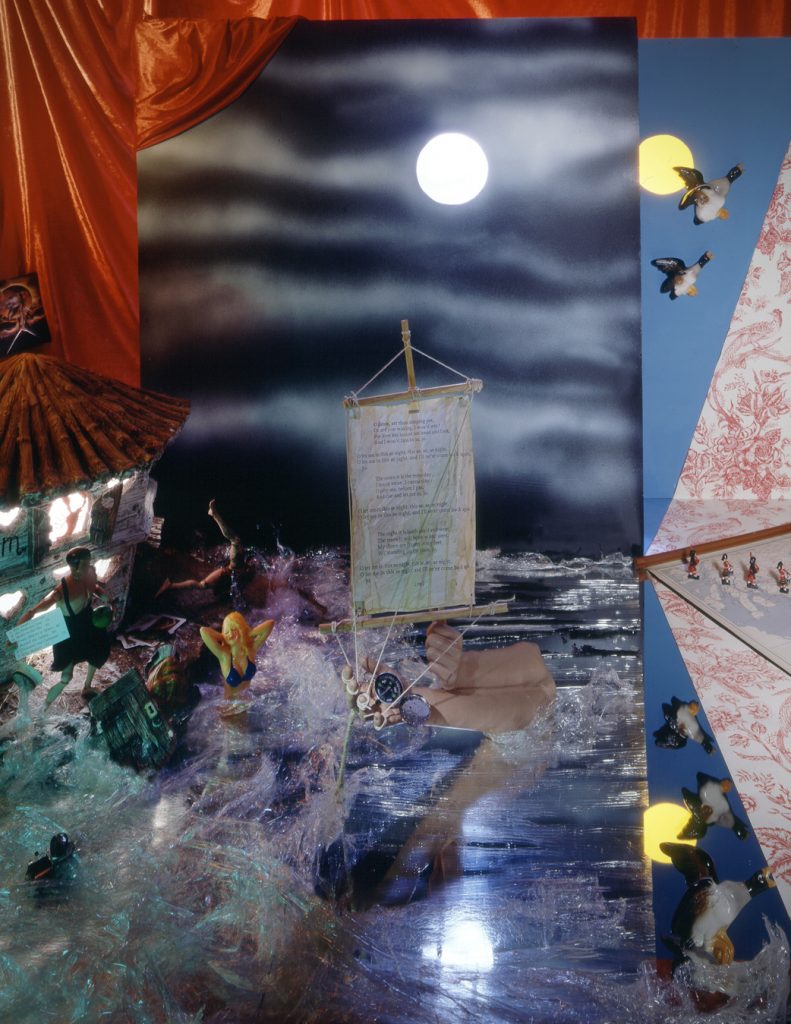

The Empty Universe

Is he Ulysses, the Fisher King or a young guy from Dundee on a Benidorn package holiday, who stands kilted, ready to embark? Colvin has always been marked by this Eliotic, Waste Land-ish melancholy. However much it works against the register, this is still a High-Romantic picture, resembling Turner’s Parting of Hero and Leander; full of bravura vapours and spray, a moonlit Cling Film (TM Copyright) sea with a beach party in progress and an adventurous – perhaps fatal – return to homeland in the offing. The drunken boat bearing a sail blazoned with Robert Burns’ Highland anthems to lechery approaches the Barbary coast in this prologue or overture. Such unheard – to the beholder of the tableau Scottish songs, complement the uniformed bagpipers and drummers who mutely cross the map of Scotland and into a skewed map of England in . . .

Siren

Colvin unsettles the conventional meanings of the female personification of Vice within his parasitised allegory. In Rejlander’s 1857 picture the Sirens call and detain a heeding youth falling on the ‘wrong’ way of life. Here Tintoretto’s Susannah is ironically used by Colvin to dismantle the notion of the temptress; Susannah is a type of purity and innocence – a triumphal figure who rejects the sexual advances of the Elders – reversing the signification of Siren and the roles attached to it. It fits, then, that this image of dissimulation against type, is composed anamorphically, a cryptic double of body and music making still-life, which generates chaste melodies, disdaining the rout of Scots bandsmen on the rocks below her right foot. An object of the voyeurs gaze of the Elders and the kited toy hero in his erotic craft, she is their nemesis and ruin. Like the virtuous Elizabeth I in the Armada portrait, she stands as a rock while a storm devours the importuning, hostile boats around her.

His Hand in Mine

Shipwrecked, the horn boat has foundered in the chambers of a malign Poseidon, while the Action-Man hero peers in on the scene with his camera. Aground in Davy Jones’ Locker with its textual sail torn from the mast, the fool’s ship with its announcement of questing male desire now resembles a temporary crucifix in penitential hands: asceticism (rather than codified ‘vice’ – another handy dandy switch by Colvin) is in the ascendence. Just as it was in Picasso’s Blue Period, aptly described by Apollinaire as: “. . . acquatic painting, blue like the damp bottom of an abyss and inspiring pit”. This submarine defile corresponds to those sacralised spaces and temples that Colvin has built in such earlier pictures as Cenotaph (1987). So Elvis presides with a look from the depths for those in peril on the sea, an almost demonaic antetype, a false idol cast into the deeps, now made amphibious by Colvin, inhabiting the worlds of water and air.

The Two Ways of Life

Near drowned, the toy sailor has toppled over a wall into a bizarre spectacle resembling the Hall of the Mountain King. The Christian narrative is continued in this central panel which has its counterpart in Rejlander’s guiding patriarch at the dividing point of the ‘two ways’. Colvin had earlier thought of painting Moses parting the Red Sea; he concluded with a version of Raphael’s St. John the Baptist in the Wilderness, his absent reed cross referring to the lashed cruciform mast of the Narrenschif in the previous panel. What does St. John preach in this context which Colvin has abducted him to? At least three topics have structured the suite and they are laid out here in Baroque splendour. The first is the confiscated culture of ‘Scottishness’: the shrine behind St. John is

a kind of Highland reliquary composed of stags bones and antlers, the bagpipes and the heraldic chart of the Scots clans, Jokanaan in the milieu of a fusty Highland lodge. Secondly. the conventional nobility of High Renaissance art is desacralised here, as it is in the use of Michelangelo’s Bacchus in the sixth panel of the suite, and in the pop-up book display of Leonardo painting. This confronts a similar cardboard pop-up vision of Elvis at Las Vegas, his voice, like that of St. John, crying in the wilderness. A semi-deified Elvis forms a final strand of meaning in this panel – an Elvis also of two ways, signified in the change of his career after his entry into the US Army, cited by Colvin as ‘Golden Boy/Soldier Boy’, in the shadow of the boy preacher St. John. This combination is powerfully reminiscent of Max Ernst’s mutations of Christian iconography in the early nineteen-twenties.

Crying in the Chapel

Together with His Hand in Mine, in Crying in the Chapel Elvis flanks the high altar and shrine of the central panel, his face found in what amounts to two transept chapels dedicated to his cult. But there are differences: instead of the cold submarine light of His Hand. . ., in this instance, (as in all the panels to the right hand side) some notional sunlight falls into a crypt space where the sailor, fetched up on pebbles. listens to the music of the sirens, but (Eliotically, again) on an archaic phonograph. He shields his eyes from an angelic vision rather than the mortifying skeleton’s dance in His Hand …. In a mirror at the far end the beholder comes under Elvis’ gaze, while gilded angels hover about a ladder. The vision, of course, cites Jacob’s Dream, but it drastically shifts the revelation of the House of God to a mournful secular site; that of Scotland dispossessed. This is discovered in the burning light of the wreath the angels hold; a row of Highland cottages under a mountain, inverted, indistinct, is compressed like the toy crystal snow sphere in Citizen Kane, into an always already lost souvenir of Scotland. This had been previously glimpsed in the central panel as a political cartoon from the late nineteenth century, showing rows of tombstones as the only assured pieces of land and property the Highland Scots had claim to. This Jacob’s Dream is soured, fatalistic.

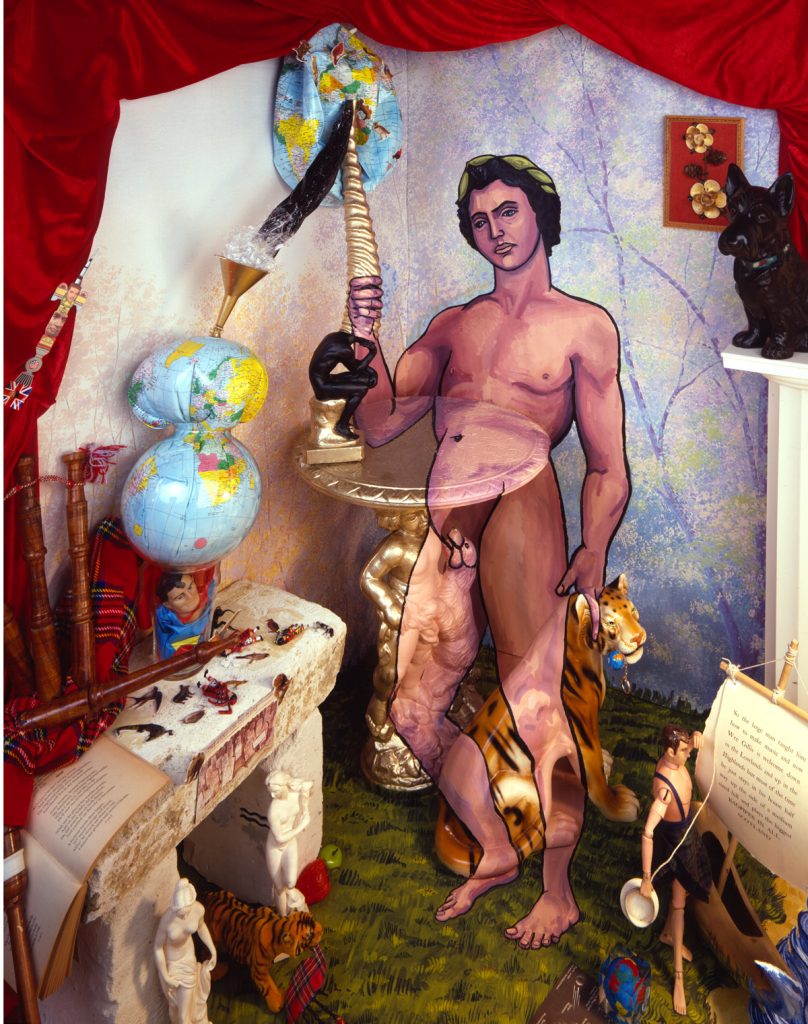

Bacchus

And now we climb out of the abysses. This, remember, should be the traditional realm of virtue, a glimpse of paradise hardworn after surmounting the rocks and caverns. Conventionally so, but Colvin has subverted this usual patterning by representing a banalised peaceable kingdom with kitsch china tigers and dogs, presided over by Dionysus-personification of excess and disorder- rather than figuring Apollo’s harmonic golden age. This is no Parnassian scene but, in Colvin’s words, “a corrupted Garden of Eden, with Bacchus intoxicated with self righteousness . . . a siren of male desire. In Bacchus the image of innocence found in Susannah as the Siren. is taken up and perverted”. In other words, we might view Bacchus and Siren as inverted pairings which function like His Hand. . . and Crying in the Chapel, to undermine the prior iconographic schemas of Vice and Virtue. Yet Colvin does strongly moralise here, with a vast simplicity, both politically and ecologically; Bacchus, travestying the figures of Industry, depletes the resources of a sagging globe, syphoning them via his puncturing horn of plenty into another distended, bloated world; a Bacchus who, like the early Nineteenth century Scottish Calvinist writer James Hogg, is “a justified sinner”.

With the Great Plenipotentiary

On the right hand edge of Bacchus the kilted toy sailor has regained his ship from a Van Gogh sea. The story. a harsh lesson for one setting out in the Narrenschif, seems wound up and at an end. On his sail is the printed conclusion to a Scottish fairy tale: the wandering hero has learned how to play the bagpipes and the reality principle is upheld. A certain neutering has taken place. However, there is still the final panel, a panel which recapitulates and pairs with the first, The Empty Universe. The sailor reappears, flailing the water as desperately as Burt Lancaster across the suburban lawns of The Swimmer. This epilogue picture – Colvin prefers to see it as the final shot of a pirate movie as the credits roll entails a reflux of desire. Burns’ found lyric of Highland eroticism. ‘The Great Plenipotentiary’, from The Merry Muses of Caledonia, is reinscribed into this declining world. On a glassy, amber sea, a galleon surges by, its sails full of manic hope, flying a chorus line from Burns’ poem as its mainmast flag.

DAVID ALAN MELLOR

University of Sussex

Review by Chicago Tribune May 10, 1991.

ACTION MAN CUTS HIS WAY THROUGH COLVIN`S MURAL-SIZE PRINTS

Abigail Foerstner CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Action Man is shipwrecked. Action Man meets the Siren. Action Man discovers ”The Two Ways of Life.” Action Man sails off into the sunset.

Scottish artist Calum Colvin adapts the serial adventure to his trademark brand of fantasy and satire in his new series of photographs, ”The Two Ways of Life.”

His mural-size color prints, on exhibit through Sept. 15 at the Art Institute of Chicago, present the further feats of our plastic hero Action Man, last seen in Colvin`s previous tongue-in-cheek photographic epics.

Elvis Presley and Superman are among the flawed gods the hero encounters amid the temples of junk-shop culture that he explores in the new series.

”Action Man is a toy I had when I was a child. He`s a narrative device and an alter ego. Every artist would like to put himself in his pictures,”

says Colvin, 29, who lives and works in London.

Colvin carries his adventure along through a cartoon cosmos of multimedia stage sets that incorporate toy soldiers, inflatable globes, photographs, paintings (his own), kitsch collectibles and verses from a bawdy Scottish ballad.

”It takes about a month to set up each one. I take the picture and tear it down,” Colvin says.

”In a number of Calum Colvin`s works of the last few years, we find ourselves in the inner sanctum of some sacred place that`s half Temple of Dendur (an Egyptian temple reconstructed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) and half Temple of Doom,” writes exhibit curator Colin Westerbeck of the Art Institute in the essay for the exhibit catalog, ”The Two Ways of Life” (published by the Salama-Caro Gallery, London, $8.95). ”Like the latter, which was the discovery of Steven Spielberg`s All-American

archeologist Indiana Jones, this temple has been penetrated by an intrepid explorer with very distinct national characteristics, a kilted Scottish hero whose mountain-climbing rope is slung across his body much as a bullwhip is across Jones`s.”

Colvin`s temples weave discordant references into a maze of illusory entrances and exits for his paradoxical fantasy worlds. ”He takes the vortex of illusion and lets it spin out of control,” Westerbeck says.

Action Man wears a rope, but his environment suggests he is truly an astronaut in a place without gravity. Even history and myth float free from their time frames and off their hallowed pedestals. Colvin`s Siren is an ironic femme fatale, a fusion of classical form, symbolic virtue and modern robotics. The angels of the temple are valentine cupids. ”The Two Ways of Life,” the centerpiece print of the exhibit, offers a takeoff on Oscar Rejlander`s 1857 masterpiece comparing good and evil. Colvin`s version compares instead the warrior and the superstar. Pictures of Elvis as soldier and singer fill both roles, flanking a painting of St. John the Baptist.

Elvis singing in Las Vegas confronts ”St. John, crying in the wilderness,” notes David Mellor in another catalog essay. Mellor, professor of American studies at the University of Sussex, identifies the pastiche of art-history and cultural references that layer Colvin`s work.

But the images maintain a visceral magnetism because they include so much that rings familiar, a sort of back lot of Western culture. Indeed, Colvin seems to invite the viewer to become lost in a maze of the familiar.

Even Action Man, ultimately alter ego for the viewer as well as the artist, cannot navigate the mysteries of such a world. He escapes to a boat on a wave of plastic wrap against a photomural sunset.

The series, while it laughs at all the throwaways of contemporary life, suggests a note of melancholy for the loss of firm bearings in the 20th Century cultural barrage. Westerbeck notes in the exhibit wall text that

”Colvin has imposed a rather elaborate symmetry on this sequence of images that each appear to be, internally, jumbled and busy.”

The images rely, of course, not only on Colvin`s imagination but on his collector`s paradise of curiosities.

”It`s a family thing. My father is a great collector of junk,” he says. ”The ostrich in an earlier picture is one my uncle collected while a missionary in Africa.”

Colvin says he ”stumbled across photography” while studying painting and sculpture at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee, Scotland. Later he studied photography at the Royal College of Art in London.

He started taking pictures of interiors and then began creating his own interiors, incorporating paintings within photographs that create a labyrinth of two-dimensional and three-dimensional planes offering their own enigmatic mythology.

What: ”Calum Colvin, The Two Ways of Life”

Where: Art Institute of Chicago, Adams Street at Michigan Avenue; 312-443-3600 When: Through Sept. 15; 10:30 a.m.-4:30 p.m. Monday, Wednesday-Friday; 10:30 a.m.-8 p.m. Tuesday; 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Saturday; noon-5 p.m. Sunday

The-Two-Ways-of-Life-catalogue

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.