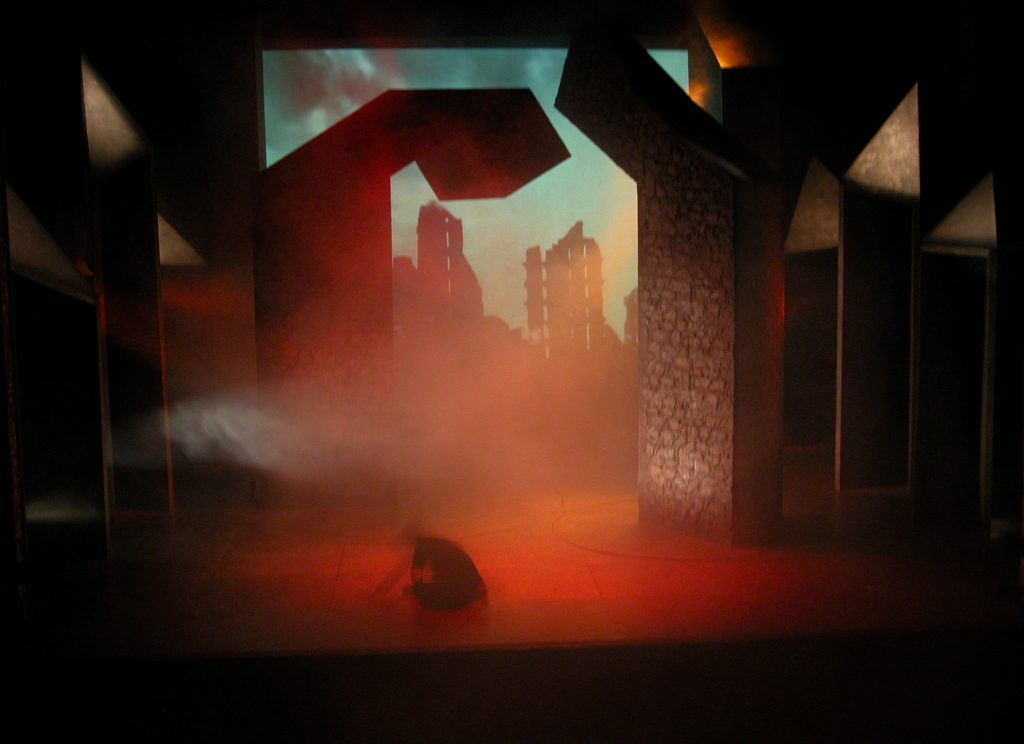

Edinburgh Lyceum, a play by Peter Arnott, set design by Calum Colvin

This commission was a set design for Glasgow playwright Peter Arnott’s Victorian drama at the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh (25/4/03 – 17/5/03). Directed by Kenny Ireland, this was a large-scale project, involving a cast of twelve actors and twenty-three scene changes. The set design utilises revolving elements, video and back projected photography to create a range of rapid scene changes depicting Victorian Edinburgh in its various social strata. Elements of early bellows cameras are alluded to in the design, (building upon Colvin’s research into early photographic technology), referencing the play’s narrative and the notion of Edinburgh as witness and recorder of historical events.

This commission was a set design for Glasgow playwright Peter Arnott’s Victorian drama at the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh (25/4/03 – 17/5/03). This was a large-scale project, involving a cast of twelve actors and twenty-three scene changes. Extensive research was conducted by Colvin, in collaboration with the Lyceum Director Kenny Ireland, into developing his previous research into the manipulation of two and three-dimensional space.Research methods involved the manipulation of the theatrical space to enable rapid scene changes from large exteriors to intimate interior spaces through the use of off-centred revolving triangular columns creating small rooms and busy, wide streets by turn. The giant, breathing bellows were constructed in order to simultaneously refer to the 1860’s Edinburgh skyline and elements of early bellows field cameras, (building upon Colvin’s research into early photographic technology), referencing the play’s narrative and the notion of Edinburgh as witness and recorder of historical events. In the suggested rooms Victorian paintings of Walter Scott, Robert Burns, Robert Louis Stevenson and Lord Byron underline the Scottish mix of success, private disaster and scandal reverberating through the narrative elements in the script. The design also utilised sound recordings, video and back projected photography interwoven into the various scenes appearing and passing like snapshots or photographic plates reinforcing the camera references.

Awarded ‘Best Design’ in the 2003 Critics Award for Theatre in Scotland.

JOYCE MCMILLAN on THE BREATHING HOUSE at the Tron Theatre, Glasgow, for The Scotsman 28.1.11__________________________________________________________

3 stars ***

IT’S ONE OF THE MANY CONTRADICTIONS of the Scottish theatre scene that while huge numbers of new plays emerge every year – often well over 100 – very few of them are ever given a chance to make their way into the permanent repertoire.

It’s therefore more than interesting to see the young Glasgow group Rekindle tackle Peter Arnott’s big, complex historical drama The Breathing House, first seen at the Royal Lyceum in 2003, and never revived since. Set in Edinburgh in the late 19th century, the play seizes on the familiar idea of the Scottish capital as a uniquely divided city, part glittering centre of reason and learning, part sewer of crumbling mediaeval slums, prostitution and degradation. The play’s hero, John Cloon, and his friend Gilbert Chanterelle, are both young men of science interested in public health; but while the widowed Cloon’s reforming idealism remains intact – finding expression in his growing love for his remarkable housekeeper, Hannah – Chanterelle’s more routine extramarital affair with a servant girl ends in cynicism and despair.

Like many of Arnott’s plays, The Breathing House is almost too rich and complex for its own good. Featuring a cast of more than 30 characters, played here by a young 14-strong company, it fairly pelts the audience with its jostling themes of degradation and desire, entrenched male chauvinism, voyeurism, hypocrisy, religious mania and social reform; and it’s questionable whether the in-the-round staging chosen by director Bill Wright is the most effective in elucidating and presenting such a huge social drama. What his production does achieve, though, is an old-fashioned but impressive sense of narrative movement and energy, particularly well captured in a powerful performance from Toni Frutin as the wonderful Hannah; and as it thunders towards a conclusion worthy of Charlotte Bronte, this fine curiosity of a modern Scottish play seems well worth reviving, not once, but many times.

Here he takes full advantage of a robust, complex, and disciplined script, and a big, 12-strong cast led by Neil McKinven, Kathryn Howden (pictured), and Forbes Masson. Essentially a tale of two cities shacked up together in an imagined nineteenth century, extremes are personified by the earnest, inquiring morality of Cloon, who marries his servant, Hannah, and utilises the new science of photography to document working women; and would-be decadent Gilbert, whose own treatment of those from downstairs is less benevolent. As brothels and old-time religion nestle up in the back-streets, auld reekie’s well-heeled self-image is chillingly blighted by death and disease.

Obvious gothic antecedents here are Stevenson and Conan Doyle, but there are nods, too, to David Lynch and Stanley Kubrick. In its brutal depiction of how sexual plague decimates societies great and small, however, it shows that even Trainspotting’s darker roots go way back.

Played on Calum Colvin’s elaborate wind of a set, twisting and turning down back alleys to get to the city’s throbbing heart, it’s a mighty, knowing, and utterly modern yarn, which only a mawkish ending threatens to spoil.

Even this is delivered with vulnerability and grace by McKinven and Howden as Cloon and Hannah, whose most charming moment comes in a wordless courtship punctuated by Matthew Scott’s score. An ambitious, unflinching work of inverse pride and rude health.

The Breathing House https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2003/apr/28/theatre.artsfeatures1

Royal Lyceum, Edinburgh

Mark Fisher Mon 28 Apr 2003 01.08 BST

Peter Arnott’s new play, an ambitious attempt to put Edinburgh in the psychiatrist’s chair, brings down the curtain on the 10-year reign of artistic director Kenny Ireland with a confident swagger. Arnott takes his cue from The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, a novel about the dark impulses lurking behind genteel appearances, which is easily read as a veiled portrait of the Scottish capital. Although nominally set in London, the novel has the taste of Robert Louis Stevenson’s native city, which embodied the contradictions of the Victorian era.

The Breathing House is about an outwardly respectable society choosing to ignore its own indiscretions, while real and metaphorical disease gnaws away from the inside. In one corner, the cynical Gilbert sets up his mistress in a brothel; in another the naive Cloon falls in love with a maid who has secrets of her own. By the time the truth comes out, the city is seething with cholera and syphilis, and someone is torching the Old Town.

That Ireland plays the melodrama straight rather than camping it up or loading it with irony gives the production a driving momentum, although it leaves some scenes exposed. Similarly, Arnott drifts close to cliche but rescues himself with Brechtian dialectics: honesty versus hypocrisy, desire versus decorum, Darwinism versus creationism and (though he doesn’t say it) Jekyll versus Hyde.

Ireland has assembled a testimonial team of formidable talent. Only the most junior members of the 12-strong cast have not taken starring roles on this stage in the past decade. By putting the likes of Neil McKinven and Kathryn Howden on a technically demanding set designed by visual artist Calum Colvin, the director leaves the theatre with a flourish that epitomises the best aspects of his tenure.

· Until May 17. Box office: 0131-248 4848.

| 2003 Critics Awards for Theatre in Scotland. http://www.theatre-wales.co.uk/news/newsdetail.asp?newsID=658 |

| The Award For The Best Theatre Production was shared between two productions. Shining Souls, directed by Alison Peebles and co-produced by her company, V.amp Productions and the Tron Theatre in Glasgow, shared the top award with Scrooge, directed and designed by Kenny Miller, the 2002 Christmas show at the Citizens’ Theatre, Glasgow. The Award For Best Male Performance went to John Kazek as Guy de Maupassant in Pleasure and Pain, by Mark Thomson and directed by him, at the Glasgow Citizens. Mark Thomson is taking over from Kenny Ireland as Artistic Director for Royal Lyceum Theatre Company. He has just announced their 2003 – 2004 season and will be directing their first production in the season Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in September. The Award For Best Female Performance went to Alexandra Mathie as Dr Vivian Bearing in Wit, the Pulitzer prize winning play by Margaret Edson, in a touring production by Stellar Quines the only Scottish theatre company who facilitate, nurture and promote primarily female artists. They are celebrating their 10th year of existence in 2003 and whose next production is Sweet Fanny Adams In Eden a site specific work in the new created Scottish Plant Collectors Garden at Pitlochry Festival Theatre this July. The Award for Best Design went to Calum Colvin, one of Scotland’s most respected photographic artists making his debut as a theatre designer. His giant breathing bellows, like the bellows of an old-fashioned camera, were designed for Peter Arnott’s impressive new Victorian melodrama, The Breathing House. It was produced by the Royal Lyceum Theatre Company, Edinburgh and directed by Kenny Ireland, who is about to retiring from being its Artistic Director after 10 years of seeing the company into its present vibrant form. The theatre critics in Scotland involved in awarding the first Critics Awards for Theatre in Scotland were: Mary Brennan (The Herald), Mark Brown (Scotland on Sunday), Neil Cooper (The Herald), Andrew Burnett (Sunday Herald), Dan Bye (The Stage), Allan Chadwick (Metro), Steve Cramer (List), Robert Dawson Scott (The Times), Thom Dibdin (Edinburgh Evening News), Ann Fotheringham (Evening Times – Glasgow), Thelma Good (EdinburghGuide.com), Joyce McMillan (Scotsman), Kenneth Spiers (Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday) and Joy Watters (The Courier). |