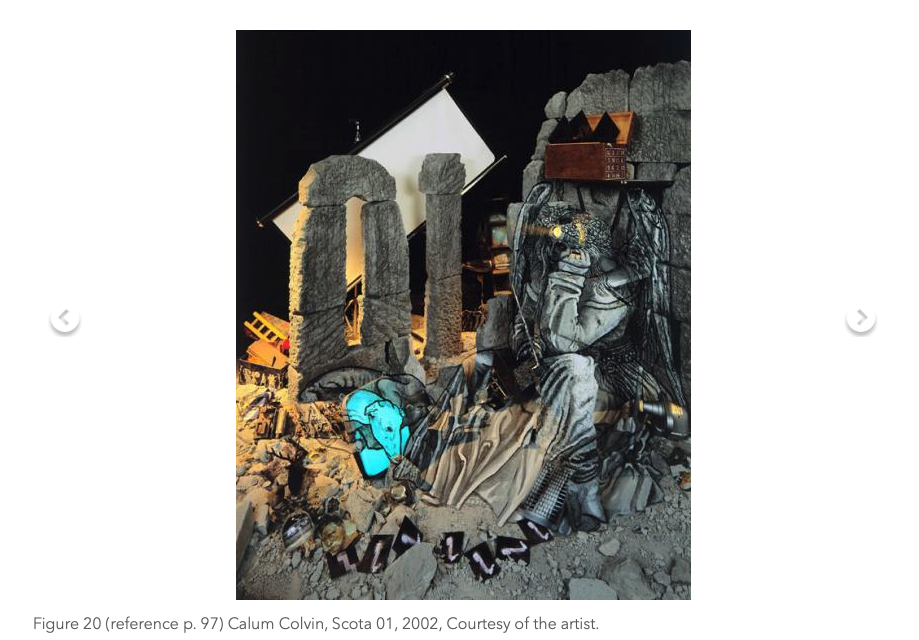

Many of us are now familiar with Calum Colvin’s remarkable series of works derived from James Macpherson’s prose poem ‘Ossian’, which was first published in the 1760s. Colvin’s work was shown at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 2002 and in a number of other venues across Scotland since then. However there is nothing like seeing the same work in another country to open up new perspectives on it.

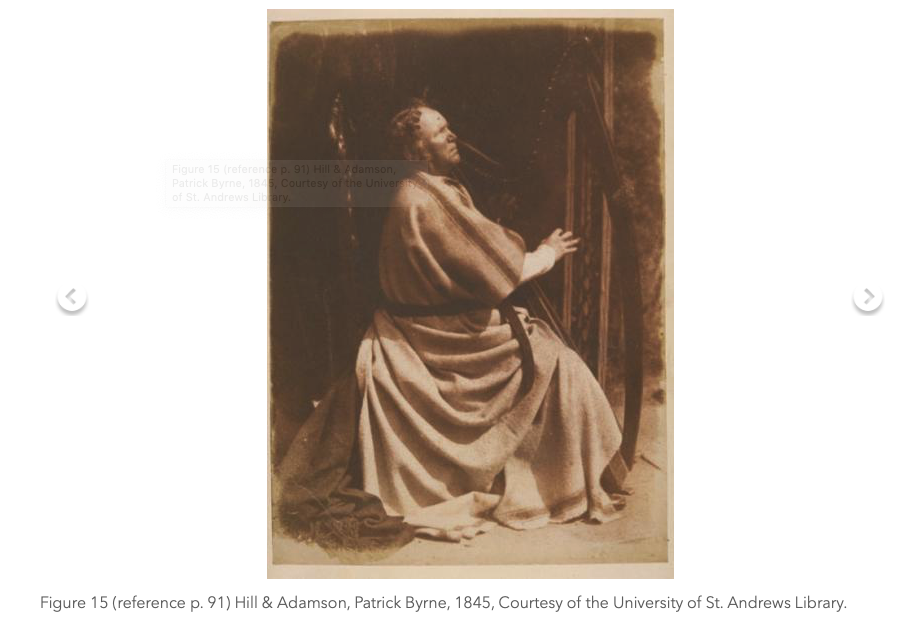

This was very much the case in November last year when Colvin’s exhibition Ossian: Fragments of Ancient Poetry was shown at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. The particular space chosen for the display had the advantage of allowing the entire sequence of Colvin’s work to be shown uninterrupted, enabling the viewer to appreciate fully his thought-provoking transformations of an image of Ossian by the 18th century artist Alexander Runciman. But my purpose here is not to review Colvin’s work, because that has already been done, but rather to draw attention to its effectiveness as a focus for international academic debate.

The exhibition was accompanied by a fascinating conference entitled Ossian then and now, organised by the Université Paris 7, UNESCO, the National Galleries of Scotland and Highland Council. It consisted of a number of intriguing reassessments of ‘Ossian’. Every contribution had a keynote quality, whether it was Howard Gaskill reflecting on ‘The Homer of the North’; or David Hewitt clarifying the associations between Macpherson, Scott and Byron; or Tom Normand exploring the nature of memory and imagery; or Colvin himself in discussion about his work with Duncan Macmillan.

It was Macmillan’s research that brought Runciman’s art back to prominence, so his interaction with Colvin in this context could not have been more appropriate. This underlined something very important to the entire event, namely the absolute contemporary relevance of the issues around Macpherson’s ‘Ossian’. These issues of cultural loss and fragmentation were brought into sharp relief by the poet Angus Peter Campbell, who pointed out the irony of the Gaelic-speaking Macpherson electing to write in English, and the route of Anglicisation of Gaelic culture to which this led. I hope that the ill-judged exhibition of Landseer’s work at the National Gallery of Scotland last year will be one of the last examples of this trend.

Campbell argued for the alternate view of Macpherson’s older contemporary, the Gaelic poet Alastair MacMhaighstir Alasdair, and underpinned his paper with readings in Gaelic and English from his own work. This contribution was the key to the day: it brought both illumination and critique to every other contribution, including my own exploration of the development of Highland imagery in terms of Macpherson and Burns rather than of Scott.

The day concluded with a visit to the exhibition itself, in which Colvin had included a new work based on an equestrian portrait of Napoleon by Jacques Louis David, the point being that Ossian was one of Napoleon’s favourite authors, and Macpherson’s words were the inspiration of many of the great artists of the Napoleonic period, including David’s students Girodet, Gerard and Ingres. As good fortune would have it, at the time of our Ossian conference there was a wonderfully designed exhibition of Girodet’s work at the Louvre. One of the key exhibits was ‘Ossian Receiving the Generals of the Republic’. What better context could we have asked for?

Murdo MacDonald is chair of history of Scottish art at the University of Dundee

Interfaces

Proceedings of the conference were published in ‘Interfaces’ Vol 27. ISBN 978-2-7442-0113-4. 1/1/2007

Interfaces is a bilingual illustrated journal focusing on the dividing line — the “interface” — between language and the image, two means of expression different and yet inseparable. This interface was displaced when the cinema made the image move, then speak, thus making time its medium and creating a new type of discourse. But the old interface between language and the static image still remains and its power is enhanced by modern technology.

Volume 27

https://www.holycross.edu/interfaces/volume-27

Duncan Macmillan Introduction (PDF) Images

Howard Gaskill “The Homer of the North” (PDF)

David Hewitt Ossian, Scott and Byron

Angus Peter Campbell Gaelic-Gallic connections, interspersed with readings from my own poetry

Murdo Macdonald Art and the Scottish Highlands: An Ossianic Perspective (PDF) Images

Tom Normand Memory, Myth and Melancholy: Calum Colvin’s Ossian project and the tropes of Scottish photography (PDF) Images

Calum Colvin (Re-) Making Ossian (PDF) Images

Memory, Myth and Melancholy: Calum Colvin’s Ossian Project and the Tropes of Scottish Photography by Dr Tom Normand

There is a remarkable coincidence of purpose between James Macpherson’s Ossian ‘translations’ of 1760 and Calum Colvin’s Ossian project of 2002 (1). Although the former was an exercise in poetic transcription, and the latter an essay in photographic invention, both were journeys of discovery and fabrication. The precise degree of Macpherson’s construction of the Ossian myth remains, even today, a moot point, but Colvin has drawn on this ambiguity to create a collection of evocative and fragmented images. These are a contemporary parallel to Macpherson’s fiction; consciously recalling the process of discovery, imitation, adaptation and simulation that has suffused the ‘original’ source.

Significantly, this method is entirely compatible with Colvin’s creative manner. Colvin is a photographer who ‘constructs’ and manipulates his images. He will fabricate a three-dimensional set, using a mixture of abandoned furniture, found-objects, toys and other kitsch memorabilia. Having set the scene he will over-paint the theatrical tableaux with a figurative illustration, often ‘borrowed’ or ‘sampled’from a traditional work of art. And, finally, he will photograph this astonishing creation, so generating a visionary ‘picture’. In reflecting on this process it is clear that the object that exists in the actual world is a fictionalised painted environment, but the result is a ‘real’ photographic study. This challenging dialogue between truth and fiction was certainly relevant to Macpherson, and it manifestly exists as a core dynamic in Colvin’s creative practice.

The correspondence between Macpherson’s ‘translations’ and Colvin’s ‘constructions’, then, is evident. But Colvin’s portfolio of Ossian images also reflects upon themes in the history and nature of photography, as well as issues in the formation and representation of identity. In this way his work combines the tropes of memory and myth within the photographic image, and in doing this endorses a tradition within Scottish photography that has consistently evoked these sentiments. In consequence this paper sets out to explore the idea of memory as it applies to photography in Scotland, and it will consider a threefold conception of memory; memory as consciousness, memory as history, and memory as myth. While locating these themes in Scottish photography generally it will place a special emphasis on the oeuvre of Calum Colvin with a particular accent on the Ossian project.

1 Reproductions of Calum Colvin’s photographs accompany the artist’s own essay in the present volume below. They can also be seen in Calum Colvin: Ossian; Fragments of Ancient Poetry/Calum Colvin: Oisein; Bloighean De Sheann Bhardachd, Tom Normand, ed., Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2002.

90 Interfaces 27 (2007-08)

Memory as consciousness.

There is a passage in W. G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz where the protagonist is confronted by a photograph. He reflects:

I heard Vera again, speaking of the mysterious quality peculiar to such photographs when they surface from oblivion. One has the impression, she said, of something stirring in them, as if one caught small sighs of despair, gémissements de desespoir was her expression, said Austerlitz, as if the pictures had a memory of their own and remembered us, remembered the roles that we, the survivors, and those no longer among us had played in former lives. (Sebald, 258)

This reflection on the mystery of photography is resonant, for the photograph may be viewed as a special kind of memory. Memory, that is, as something that will ‘surface from oblivion’, in which there is ‘something stirring’, and which may release these ‘small sighs of despair’. We all of us, perhaps, have photographs of family, and friends, and loved-ones, that we treasure as reminiscence, or as recollection. These are the transcripts of the generations, handed through families and groups to aid recall and to initiate storytelling. For the generality of people these photographs are recondite and perhaps meaningless but for each holder of the image, for the owner of the album, they are particular and familiar.

Such photographs, then, are memory, and in many cases they take the place of memory. That is to say that the photograph becomes the recollection; for, if memory is conceived as something like a dream-world, fractured and surreal, then the photograph is a stable recollection, a truth. As Roland Barthes insisted ‘the very essence, the noeme of Photography…will therefore be: “That has been”’ (Barthes, p.76-7). This essential photographic truth, this thing ‘that has been’, is held and retained as memory.

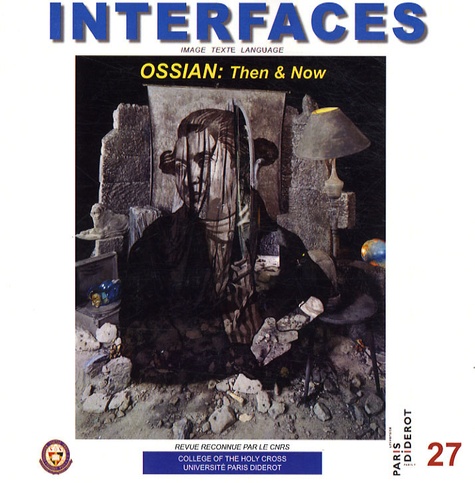

Many of the photographs we now venerate as art might be reclassified in this manner. The photograph, in its infant years during the 1840s and 1850s, was principally developed as a medium for the dissemination of the individual portrait. These portraits were both celebration and memorial. They offered a vision of the person and a testament to their character, while simultaneously presenting a memory of their being at a particular time, a memorial. Barthes, again, is helpful here for he insisted that ‘however “lifelike” we strive to make it […] Photography is a kind of primitive theatre, a kind of tableau vivant, a figuration of the motionless and made-up face beneath which we see the dead’ (Barthes, 31-2). So that we may view Hill and Adamson’s artful construction of, say, Patrick Byrne (c.1797-

91. Tom Normand: Memory, Myth and Melancholy: Calum Colvin’s Ossian project and the tropes of Scottish photography.

1863) [FIG.15], the eminent and blind Irish Harpist who visited Edinburgh in 1845, as precisely this dual configuration; recording Byrne’s features and his status in a ‘tableau vivant’, while simultaneously memorialising his life in this ‘motionless’ pose. Of course, Hill and Adamson have also composed Byrne in the style of Ossian. The blind harpist is viewed in profile and decorated with a primitive plaid- like robe. The ‘look’ of the photograph has been designed to connote the famous image by the neo- classicist Alexander Runciman who created a sketch of Ossian Singing in 1772 [FIG.4 B]. Moreover, the setting of Byrne within this provocative context signals a conscious desire to connect with the myth of the great Celtic bard, Macpherson’s own Ossian.

However, it is possible to extend this sense of memory to contemporary portraiture in, for example, Robin Gillanders’ evocative portrait of the artist Ian Hamilton Finlay [FIG.16]. Here the shadow and light are constructed to present a sense of drama, certainly, but also a kind of historical resonance; a memory of Finlay’s being and life’s work; almost, it might be said, the atmosphere of a mausoleum. Gillanders is conscious of the ‘shadow’ that sits in the background of each portrait study, the shadow that Barthes recollects, that is, the spectre of mortality. The impression of dramatic contrast, and the dark shadow-play of the photograph evoke the depth of mystery that allies this image not only to the realm of memory and memorial, but also to the twilight world revealed in Colvin’s Celtic visions.

Photographs, then, carry multiple and complex meanings all held under the banner of memory. It is these slippages of meaning that Calum Colvin consciously recalls in his portrait studies. Whether it is the constructed tableaux of a contemporary portrait, as in the subtle iconography of his commissioned study of the composer Portrait of James MacMillan, or, in the imagined world that he creates in commemoration of the Scottish national bard Portrait of Robert Burns [FIG. 27], Colvin is mixing memory and history and memorial. In all, these photographs become a kind of testament to an event that is passing or past. In this remarkable way art, the photograph, represents life, but becomes death, or rather becomes memory and memorial.

This, of course, is the import of Barthes’ remark that such images are ‘…a figuration of the motionless and made-up face beneath which we see the dead’ (Barthes, 31-2). Less dramatically, perhaps, John Berger has offered a comment based on the pragmatic use of the photograph

‘What served in place of the photograph before the camera’s invention? The expected answer is the engraving, the drawing, the painting. The more revealing answer might be: memory. What photographs do out there in space was previously done within reflection’. (Berger, 50).

The idea that the photograph, and photography, offer to the mind a space for reflection is seductive.

92 Interfaces 27 (2007-08)

In the case of the photograph that space is less an opening for the imagination, and more a room where memory is encountered. In this way the photograph represents, at the first level, memory as consciousness. The photograph is a recalled awareness, a remembered perception, one that opens the door into an individual’s history.

Memory as history.

The photograph in this highly individualised sense is, most probably, the common currency of the medium. This is the point at which we all engage with photography; this is personal. However, it is also appropriate to understand photography in an historical sense. Evidently, the photograph has documented the historical moment, and moments that we are all familiar with; from Desderi’s Paris Commune: Bodies of Insurgents, to Hung Cong Ut’s Children Fleeing a Napalm Strike in Vietnam. Photographs like these have both recorded, and, it might be argued, changed history. But, there is a more specialised sense in which the photograph engages history. It may be possible that the photograph can evoke a kind of historical memory, a site of collective remembering. In his introduction to Pierre Nora’s epic intellectual adventure Realms of Memory Lawrence D. Kritzman notes that: ‘Pierre Nora’s Realms of Memory (1984-1992)…seek(s) to locate the ‘memory places’ of French national identity… The history of memory is realised through the imaginary representations and historical realities that occupy the symbolic sites that form (French) social and cultural identity’. (Nora, ix). These ‘memory places’ are, importantly, the loci of a collective psyche. Nora himself makes much of this difficult association of memory and history

‘Memory is life, always embodied in living societies and as such in permanent evolution, subject to the dialectic of remembering and forgetting, unconscious of the distortion to which it is subject, vulnerable in various ways to appropriation and manipulation, and capable of lying dormant for long periods only to be suddenly reawakened. History, on the other hand, is the reconstruction, always problematic and incomplete, of what is no longer…Memory is rooted in the concrete: in space, gesture, image, and object. History dwells exclusively on temporal continuities, on change in things and in the relations among things. Memory is an absolute, while history is always relative’. (Nora, 3).

Here, memory and history are juxtaposed in methodological terms, but it is possible to view this polarity as an interdependent project; history may be presented as an imagined projection based on memory. Most engagingly, it may be presented in this way in the photograph.

93. Tom Normand: Memory, Myth and Melancholy: Calum Colvin’s Ossian project and the tropes of Scottish photography.

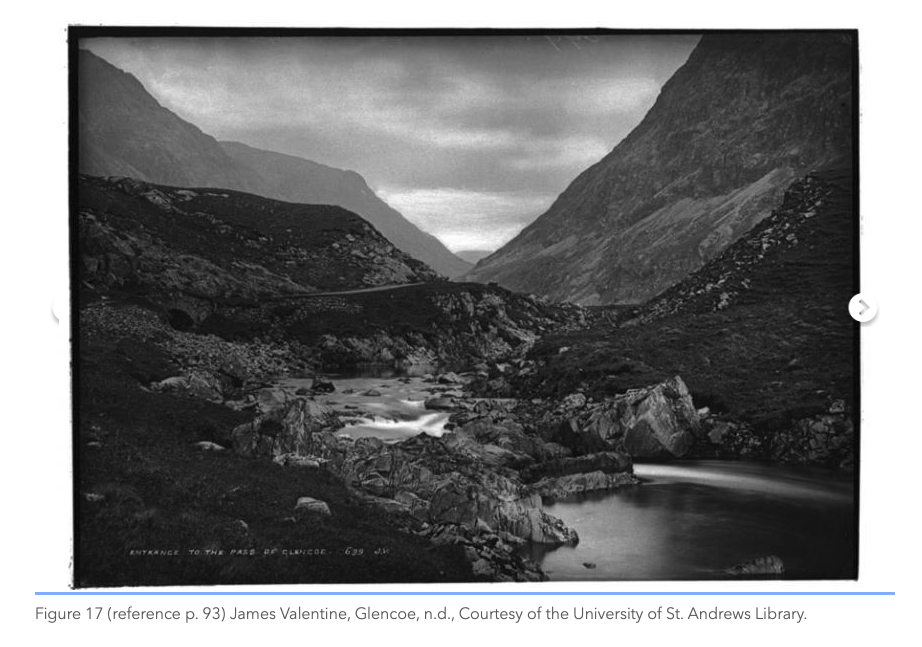

This sense of historical memory as something concretely embodied in symbolic sites has been a familiar trope of photography in general, and, in particular, of landscape photography; so that, the history of landscape photography in Scotland has been marked by a constant reference to the ‘landscape of association’. This is evidenced in the obsession that early photographers, like George Washington Wilson and James Valentine, had with the landscape of the Scottish Highlands. Both these photographers celebrated the ‘memory places’ of Scottish history, scouring the Highlands for sites that resonated in the nation’s chronicles. Here, photographs of, for example, Glencoe, abound [FIG.17]. These are viewed simultaneously as an archetype of the ‘land of the mountain and the flood’; as the site of the infamous ‘Massacre of Glencoe’ where the Clan Campbell, acting as agents of the crown, slaughtered the indigenous Macdonalds in 1692; and indeed, as the site of ‘Ossian’s Cave’. Evidently, throughout this trope, landscape becomes the very embodiment of history and of memory.

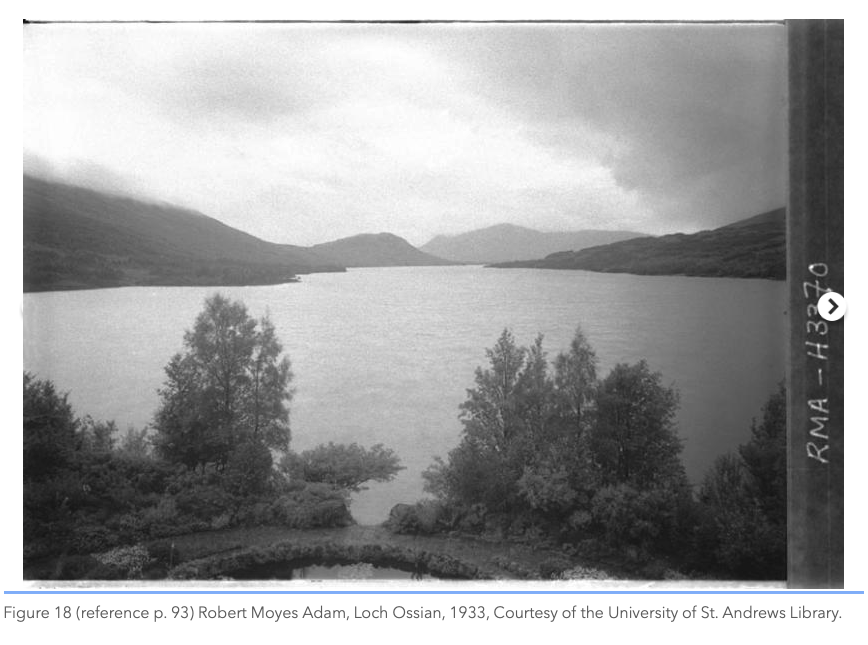

This approach is not simply the outcome of a sentimental Victorian romanticism. Indeed, in the twentieth-century it became marked in Robert Moyes Adam’s evocative landscape images of mountains, castles, glens and lochs; like, for example, Loch Ossian, 1933 [FIG.18]. Significantly, Calum Colvin would ‘sample’ Adam’s Highland landscapes in a number of his own constructions, including references in The Explorer, 1985, and in Jacob’s Ladder, 1989.

It is a commonplace to contend that these panoramic landscape images were created for the developing tourist industry, one of those new social phenomena that came to define the distinctive character of modernity in the nineteenth century. In this frame they were the emblems of ‘wilderness’ and difference; a marked contrast to the ‘civilised’ urban environment that contemporary populations were coming to regard as a natural habitat. Here, the landscape photograph illustrated not just the tourist memento postcard or booklet, but the multitude of travel books and guides, and of course functioned as a formal memory of a tourist visit to some ‘different’ land. However, the selection of relevant sites was consistently determined by historical association. So, the Pass of Killiecrankie, the Wade Bridges, the Glenfinnan Monument, the deserted crofts of Wester Ross, ruined Brochs, carved Celtic crosses, and every kind of spectacular, austere, sublime castle; these were the stalking grounds of the landscape photographer. All such images allude to, and memorialise, the history, culture and identity of the Scottish nation and its people. Sites like these, then, provide what Kritzman has called a ‘symbolic encyclopaedia’ of the national identity. More powerfully, perhaps, photographs of these sites realise that symbolism in concrete form (Barthes’ ‘that-has-been’) and preserve it as memory. Hence, history, now understood as memory, is released to a collective experience, not purely through academic research, but through an immediate and largely unmediated visual experience. ‘That-has- been’ becomes ‘this-is-us’.

94. Interfaces 27 (2007-08)

Memory and myth

Of course, all of this assumes a settled, and an uncomplicated sense of history and identity. In any nation this is not so, and not in Scotland; the story of Ossian being a case in point. In fact these visual images, these photographs of symbolic sites, do not simply recollect collective memories, but they construct a collective memory. That is, their presence acknowledges and reifies a national story that takes the form of a potent myth. Such a myth, while informed by history and at some level ‘true’, or at least ‘accepted’, is nevertheless a symbolic system, a ‘constructed narrative’.

It is at this level, in the ‘constructed narrative’, that Calum Colvin’s photographs express the idea of the photograph as memory and the photograph as myth. Colvin has long recognised that the photograph, even the most compelling documentary photograph, creates a kind of fiction. In every sense the photograph is a ‘point of view’. His oeuvre is largely generated through a sense of the ways in which a photograph can appear to contain a settled subject, but will subtly undermine that subject by introducing counter-point and challenge. Hence, in Colvin’s work, the myth of ‘Scottishness’ is presented in terms of symbolic sites, recognisable narratives and cultural archetypes, but is disrupted by the inclusion of kitsch stereotypes and comic interventions. The ‘realm of memory’, then, is both recognised and reprised, yet is contested and undermined. In fact its nature as myth is explored and adapted in a way that reveals the functioning of cultural narratives and of photographic imaginings.

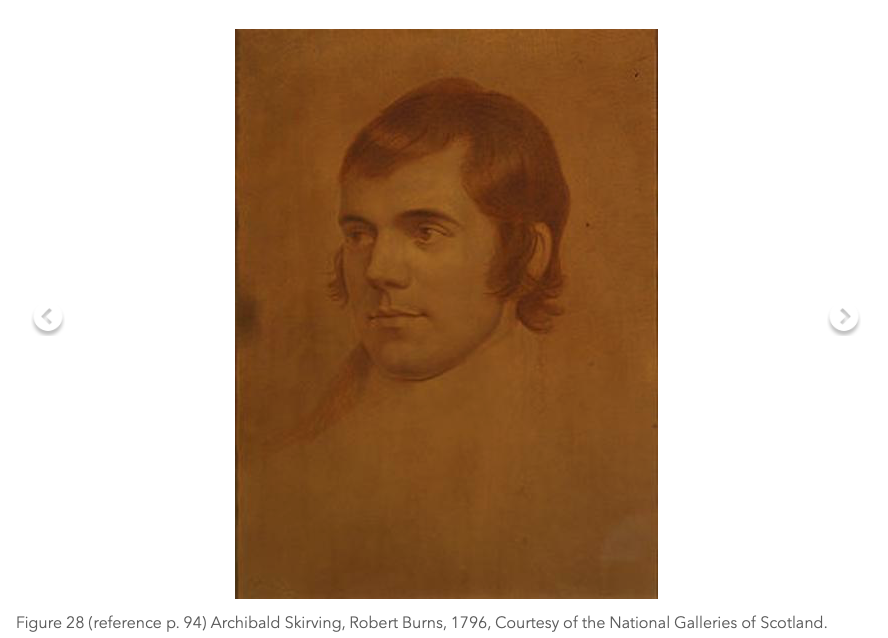

The Portrait of Robert Burns [FIG.27], an elliptical reference within the Ossian project, is a case in point. The image of Burns is based upon the drawing of the bard by Archibald Skirving which is held in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery [FIG. 28]. This drawing is itself based upon the more famous painting of Burns by Alexander Nasmyth, and so the idea of translating, layering, and composing so prevalent in Macpherson’s poetry is already reprised. But, Colvin’s painted head of Burns is set against the reconstituted landscape of his Ossian portraits, and the scattered fragments of Ossian’s world have been, miraculously, reconstructed as a bookcase. Moreover, throughout this restored setting the references to Burns’ own poetic achievements are manifest; the red rose, the green rushes, the heart juxtaposed with the stag’s antler. These are the instantly recognisable symbols of the bard’s craft and art. Nevertheless, they are rendered, in part, as stereotype and parody for they are represented in the form of kitsch mementos and comic paraphernalia. Likewise the notion of a core or essential Scottish identity, partly rooted in Burns’ role as ‘national bard’, is disrupted by the symbolic ‘Maori’ head; this last being kin to the Celtic patterning of Ossian’s representation, and a reflection on the problematic nature of national or racial creation myths. In all, then, the ‘realm of memory’ is conflated with the ‘realm of myth’.

It is for this reason that the subject of Ossian has been so seductive for Colvin for it is

Tom Normand: Memory, Myth and Melancholy: Calum Colvin’s Ossian project and the tropes of Scottish photography. 95

acknowledged that devastating slippages of memory and meaning run through the history of Ossian’s presentation and reception. In many ways the story is both a mythic representation, and is its own myth. Moreover, the challenge to the work as ‘truth’ is a challenge also to the notion of an authentic national story, of a collective cultural memory, of a settled historical account, and, in this case, of the veracity of the photographic image. All of these uncertainties are the forum of Colvin’s art, and they are presented, in various forms, in the landscape of his Ossian images.

This phenomenon is worthy of discussion within the broader context of this paper. It might be suggested that Macpherson’s Ossian was itself a response to the perceived loss of a national story, a Scottish national identity, in the period after the Act of Union and the amalgamation of the Scottish nation into a United Kingdom of Great Britain. In other words the desire for a mythic national narrative emerged at the point where the practical history was subsumed. In another context, Kritzman, also, has reflected upon this idea:

‘The creation of “realms of memory” is the result of modern society’s inability to live within real memory; the consecration of a “realm of memory” takes place because real environments of memory have disappeared. The projection of a “realm of memory” is therefore the sign of memory’s disappearance and society’s need to represent what ostensibly no longer exists. […] But for now, what remains of the idea of nationhood is engendered by a nostalgic reflection, articulated through the disjunctive remembrance of things past. In a way, one might argue that the quest for memory in the contemporary world is nothing more than an attempt to master the perceived loss of one’s history’. (Nora xii; xiii).

What is significant here is the notion that the return to ‘realms of memory’ (of which the photograph is one dimension) is a rational reaction to rapid change and development in the contemporary period. Hence, the reflection on Macpherson’s Ossian is pertinent because we live in a parallel, social and cultural, universe. If Macpherson was responding to incorporation within the larger project of the British Empire, then currently the concern with myth and memory may be viewed as a response to our incorporation in a globalised culture and environment.

Recently Gilles Lipovetsky has called this new, globalised, environment ‘hypermodern’. This he views as a ‘second cycle of modernity’ and a stage beyond the ‘postmodern’. Of this condition he notes:

‘What defines hypermodernity is not exclusively the self-critique of modern institutions and forms of knowledge, but also revisionary memory […] it is marked by the return of traditional

96 Interfaces 27 (2007-08)

landmarks and of ethnic and religious demands based on types of symbolic heritage that go back a very long way and stem from diverse origins. In other words, all the memories, all the universes of meaning, all the forms of collective imaginary that refer to the past and that can be drawn on and redeployed to construct identities and enable individuals to find self- fulfilment’. (Lipovetsky, 67).

If we accept this context the memories, history and mythic stories presented in the world of photography, the world we have been observing here, become one site of this longing. More than this, it is an irresistible site, one that functions in reaction to the repression of memory in the contemporary world. Lipovetsky, again:

‘…in celebrating the pleasures of the here-and-now and the latest thing, consumerist society is continually endeavouring to make collective memory wither away, to accelerate the loss of continuity and the repetition of the ancestral. The fact remains that, far from being locked up in a self-enclosed present, our age is the scene of a frenzy of commemorative activities based on our heritage and a growth in national and regional, ethnic and religious identities […] a groundswell of memory’. (Lipovetsky, 57).

This ‘groundswell of memory’, in all its complexity and with all its contradictions, is precisely what photography offers, and is the covert theme of Colvin’s Ossian.

Memory and melancholy.

This is not to say that these memories are unproblematic, nor do they exist as a salve to contemporary experience. In fact, these ‘memory places’ can be both disturbing and melancholic. Barthes, in Camera Lucida consistently returns to the idea that the photograph embodies a kind of ‘death’. His key phrase is ‘the melancholy of the Photograph itself’ (Barthes, 79). Even Sebald, in ‘Austerlitz’ reflects on this unsettling character of photography. In the addenda to his first confrontation with the photograph of himself when young he recalls, ‘The picture lay before me, said Austerlitz, but I dared not touch it…hard as I tried both that evening and later, I could not recognize myself in the part. I did recognize the unusual hair line running at a slant over the forehead, but otherwise all memory was extinguished in me by an overwhelming sense of the long years that had passed’ (Sebald, 259).

The photograph impels the reflecting viewer towards a kind of tragedy. Its role as memory conjures up intimations of mortality and of loss. This, it might be said, is the import of Colvin’s

Tom Normand: Memory, Myth and Melancholy: Calum Colvin’s Ossian project and the tropes of Scottish photography. 97

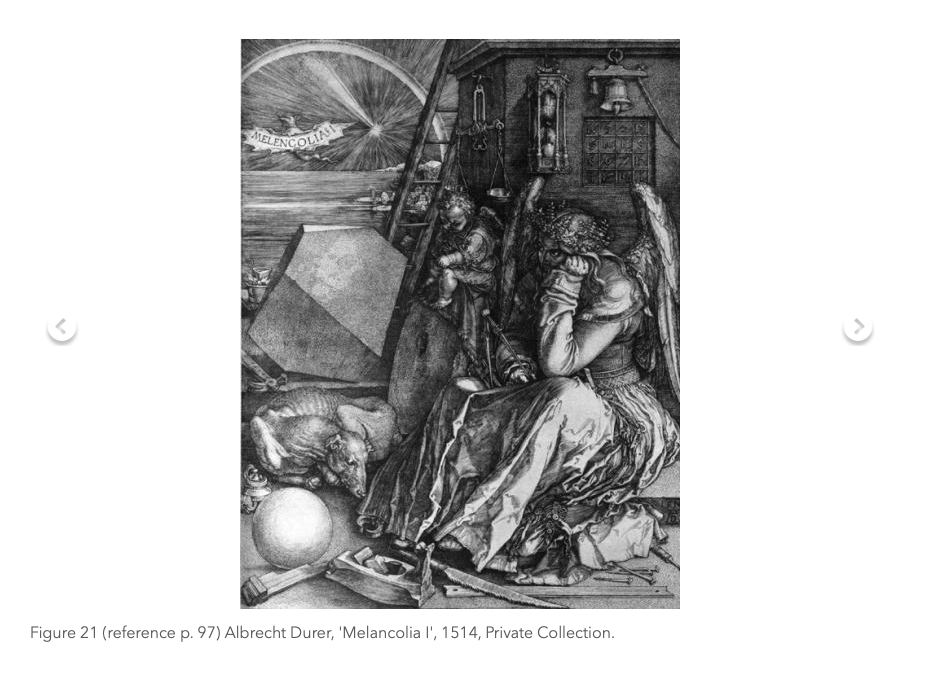

‘Fragments’ [FIG. 24a- 24h]. Interesting, also, that Colvin should include Scota 01 [FIG. 20] in his assemblage of Ossian images, especially with its source in Durer’s Melancolia 1 [FIG.21]. Here is the acknowledgement of the photograph, not only as memory, and history, and myth, but as the portent of melancholy. Always, the photograph is a kind of evidence of something ‘that-has-been’ and that is now lost. Even in the most casual of snapshots there is the substantiation, and the memorial, to a moment. And so, ‘One has the impression, she said, of something stirring in them, as if one caught small sighs of despair, gémissements de désespoir was her expression, said Austerlitz, as if the pictures had a memory of their own and remembered us, remembered the roles that we, the survivors, and those no longer among us had played in former lives.’ (Sebald, 258)

Melancholy is the inevitable sense of the photograph. It is also the pervasive sensation within Macpherson’s Ossian. And so the photographic moment collides with mythic representation and is fully expressed in Calum Colvin’s extraordinary images.

98 Interfaces 27 (2007-08)

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland, Camera Lucida, London: Vintage Books, 1993.

Berger, John, About Looking, London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative, 1980 Lipovitsky, Gilles, Hypermodern Times, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005

Nora, Pierre, Realms of Memory I, New York: Columbia University Press, 1992. Normand, Tom, ed. Calum Colvin: Ossian; Fragments of Ancient Poetry/Calum

Colvin: Oisein; Bloighean De Sheann Bhardachd, Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2002. Sebald, W. G. , Austerlitz, London: Penguin Books, 2002.