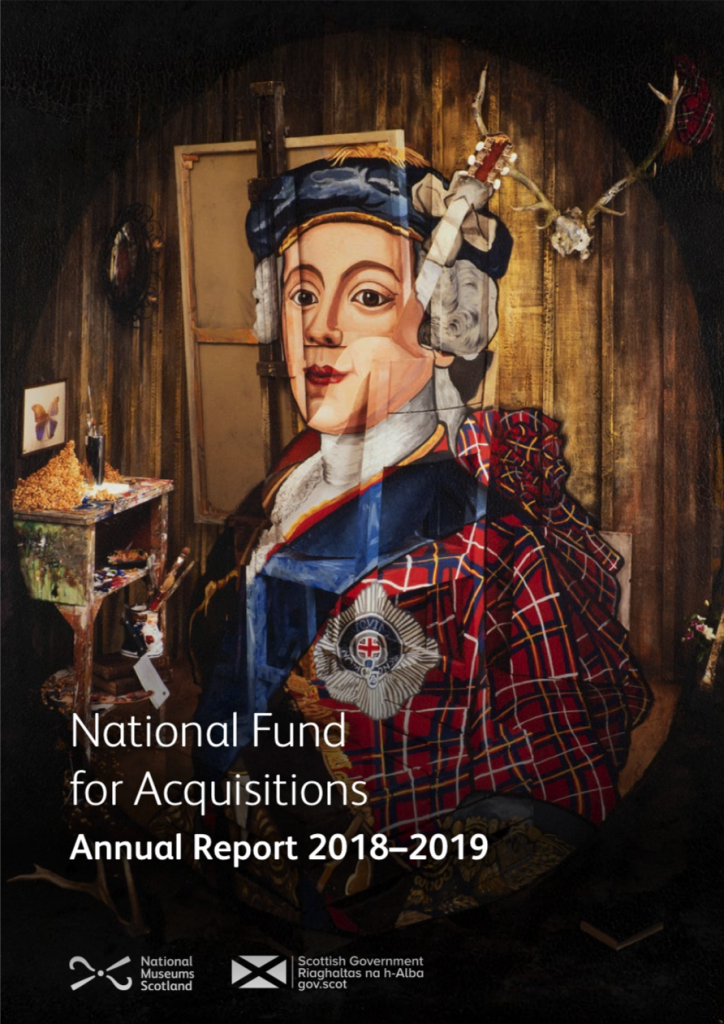

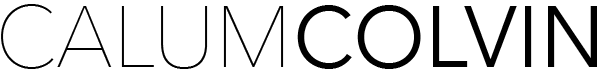

‘Jacobites by Name’ was a solo exhibition of 27 new works by Calum Colvin at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh (14 November 2015 – 27 March 2016), presented as an intervention within ‘Imagining Power: The Visual Culture of the Jacobite Cause’,

the Gallery’s extensive permanent display of Jacobite visual material. Marking the 300th anniversary of the 1715 Jacobite Rising, this exhibition-within- an-exhibition explored the evolution of factual and mythologised representations of the historical events, re-evaluating their influence in contemporary Scotland and providing new possibilities for re-interpretation.

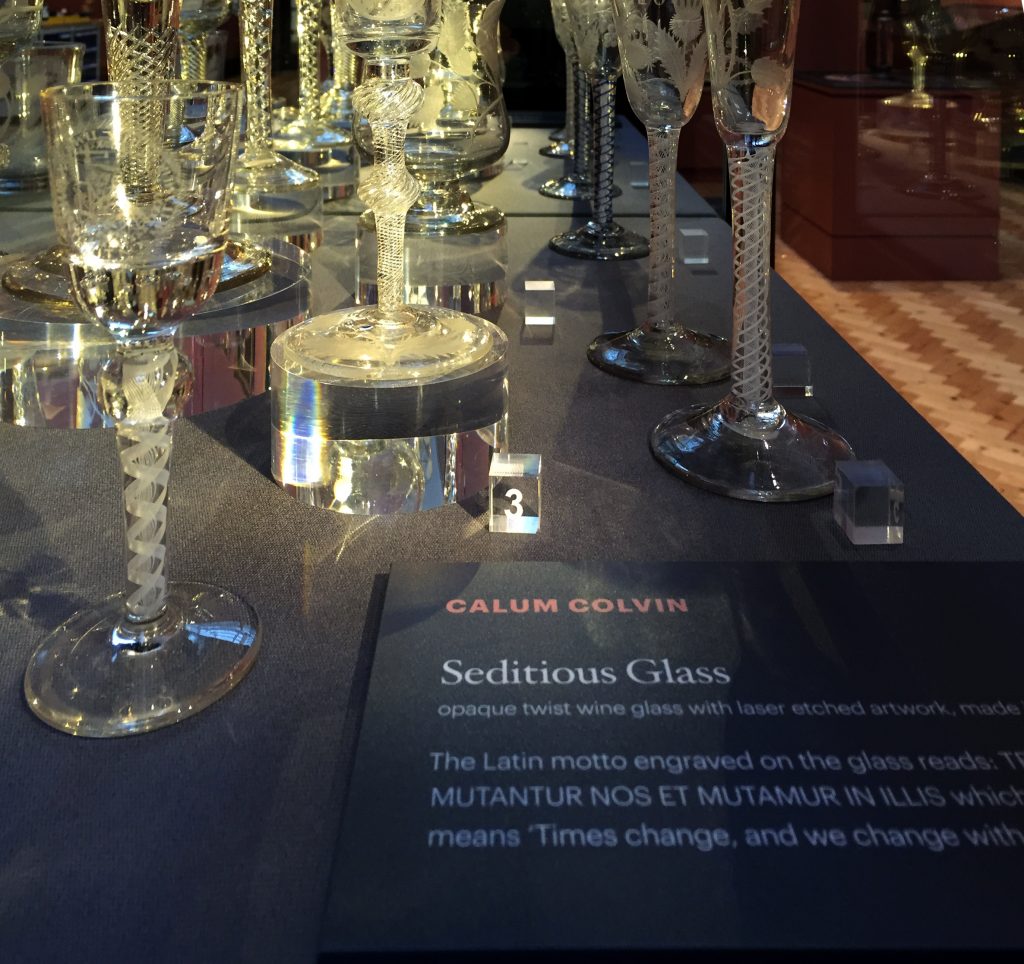

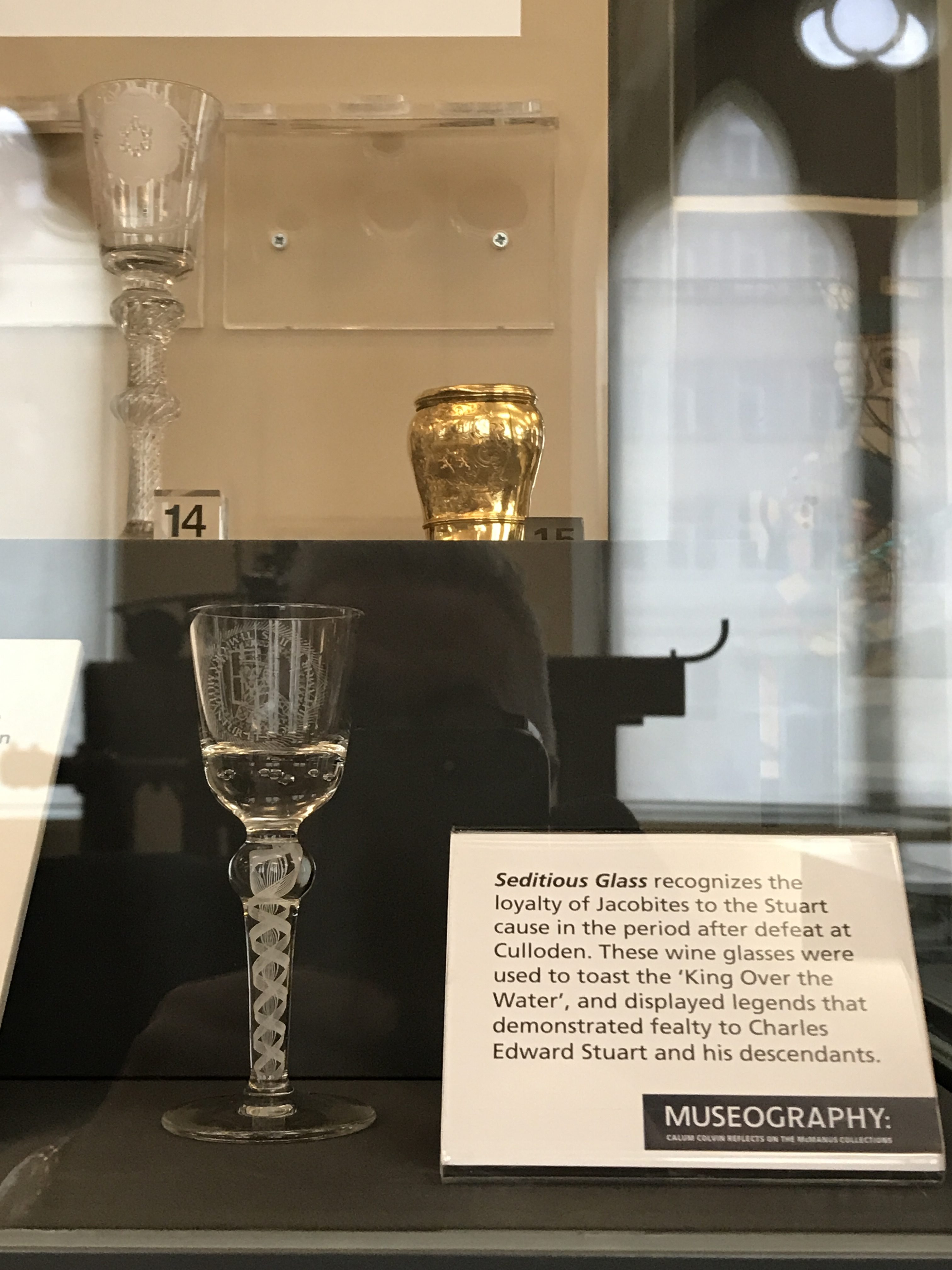

Colvin’s exhibition was underpinned by a Leverhulme-funded research project in which the artist investigated the legacy and symbolism of the Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1745 though their related material culture in museums and historically significant sitesacross the UK. The research led to a new body of photographic works that reframe popular symbolism found in glass and ceramic objects, optical devices and the repository of ephemera that reference the complex legacy of the Jacobite cause.

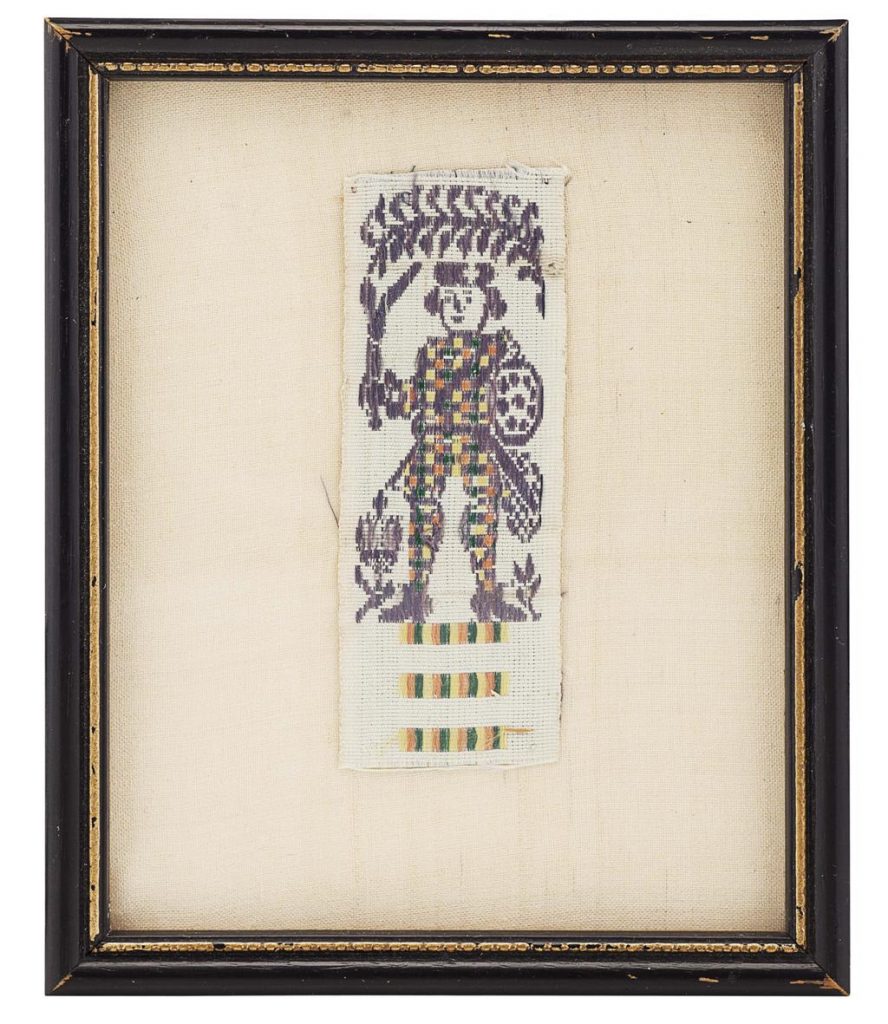

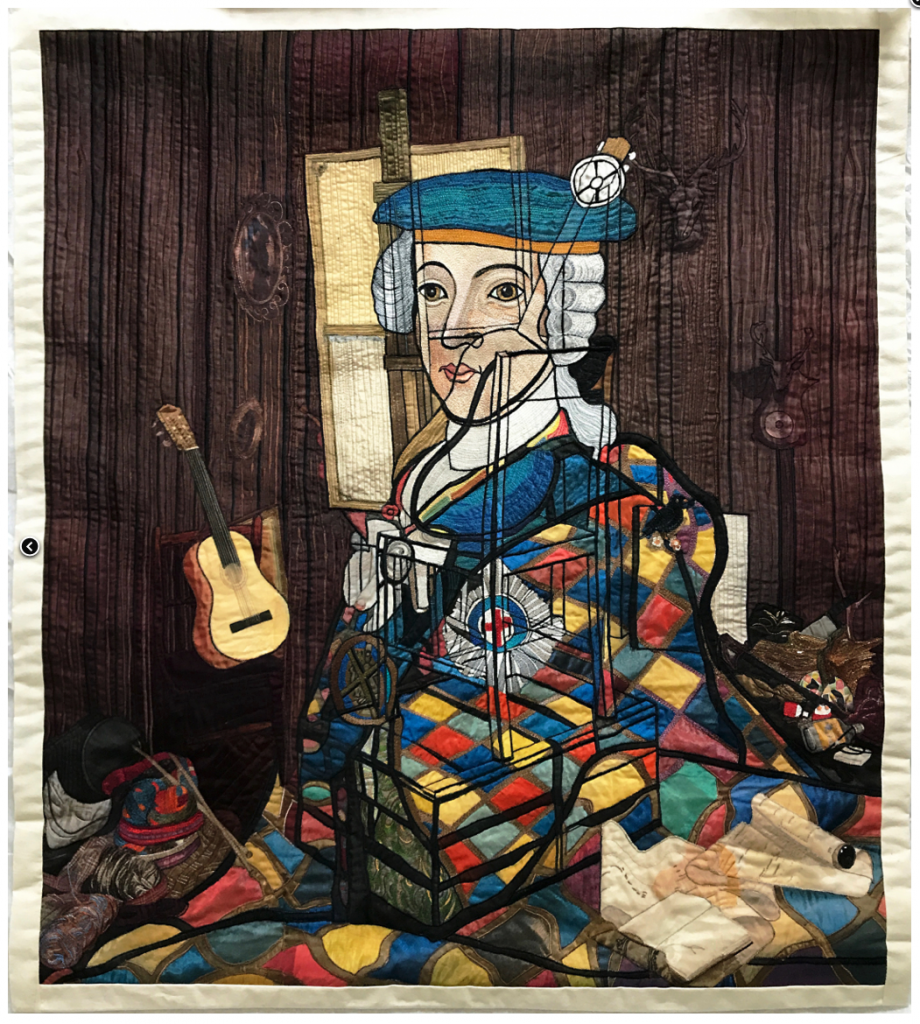

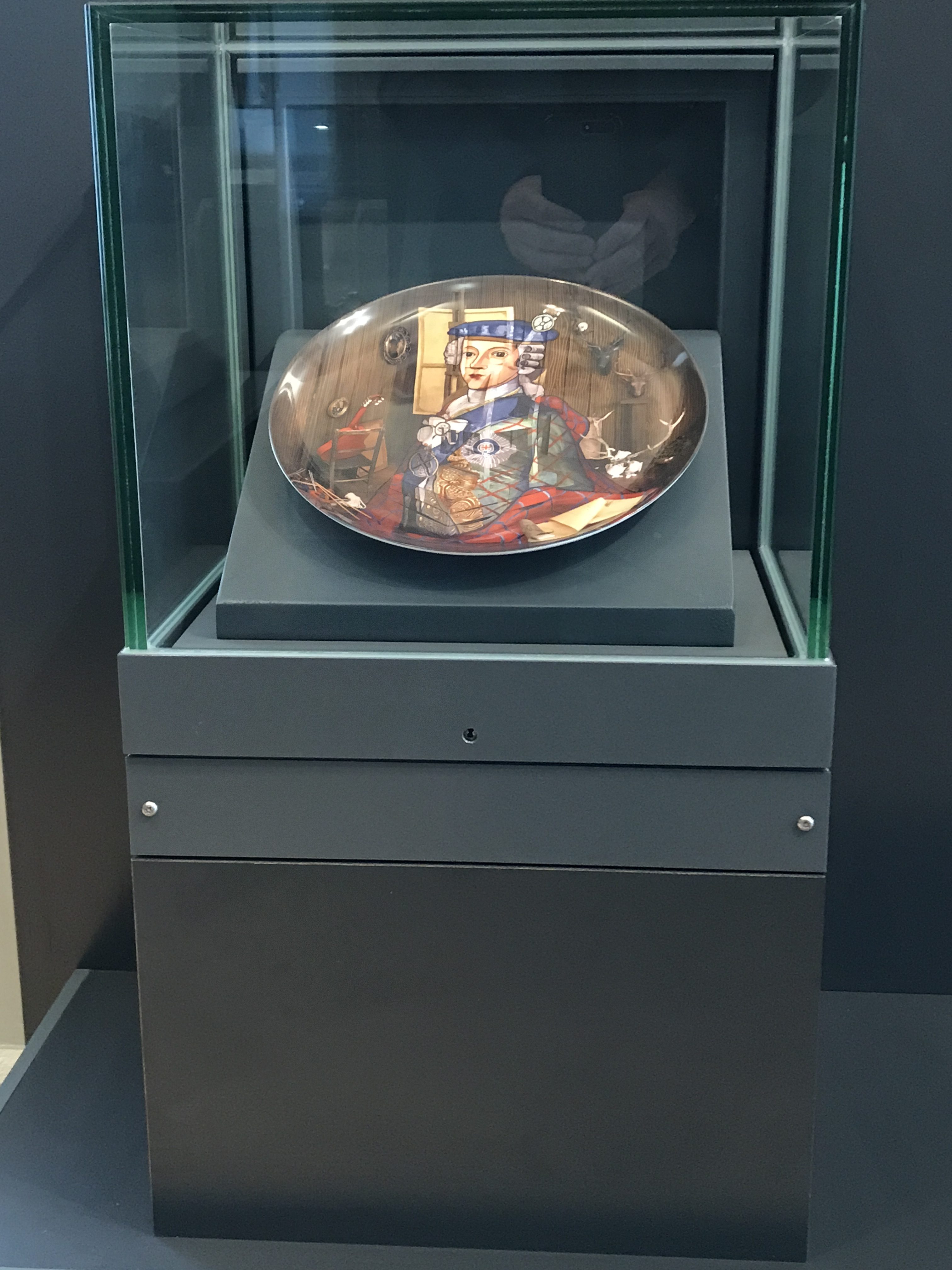

The artworks are the result of a unique technical process where the artist constructs stage-sets relating to the subject, which he then paints with imagery alluding to the matrix of meanings embedded in the iconic historical period. Through repeated iterations, the images evolve from photographs to framed canvases, glassware, ceramic, embroidery, prints and objects, an anamorphosis and a large lenticular print: the process evoking the historical reductionism and romanticisation of the Jacobite cause.

The exhibition attracted 44,921 visitors, national press attention, touring to Inverness Museum & Art Gallery (2016) and The Scottish Parliament (2017). The installation and the works were contextualised and documented by Colvin and the Gallery’s Senior Curator Julie Lawson in an artist’s book, which also featured new writings by Professor Fiona Stafford and responses by poets Kathleen Jamie and Rab Wilson.

Timeline

2014

Awarded Research Fellowship from Leverhulme Trust for ‘Jacobites by Name’ project

‘This project explores the legacy of the Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1745. The research

will lead to a body of artworks exploring this defining moment in Scottish history. A basis

of constructed stage-sets, composed from objects and artefacts relating to the subject, will

be painted with imagery alluding to the matrix of meanings embedded in this iconic historical period. The photographs will generate a nuanced semiotics of the key moments and wider myth of the Stuart dynasty: an open-ended series of references, of riddles and puzzles, of ‘‘facts’’ and beliefs that connote the multifaceted legacy of the Jacobite Rising.’

(March 2014)

Invited By National Galleries Of Scotland To Make The Exhibition/Intervention ‘Jacobites By Name’

To be installed within the permanent display ‘Imagining Power: The Visual Culture of the Jacobite Cause’ in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh.

(April 2014)

Research Visits

The Fellowship enabled Colvin to conduct research visits to numerous collections and sites of significant Jacobite interest, including Inverness Museum & Art Gallery, The Glenfinnan Monument, The West Highland Museum, and Culloden Battlefield Site and Visitors Centre. Colvin was also able to study the Drambuie collection of Jacobite ephemera, which are housed in the National Galleries of Scotland repository in Granton, Edinburgh. This was an invaluable resource, as was the print collection at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh. Colvin was also able to spend several days studying the permanent collection in the Jacobite Gallery in the SNPG.

(Sept – Nov 2014)

2015

Studio Work

Practice-based research, creating new artworks, including photographs, glass and ceramic objects and optical devices. Exhibition installation planning.

(October 2014 – October 2015)

Jacobites By Name’ Exhibition/Intervention At The Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

(14 November 2015 – 28 March 2016)

Press Coverage

● The Scotsman (feature). (13 November 2015)

● The Scotsman (review). (30 November 2015)

● The Times (feature). (4 December 2015)

● Scottish Society for the History of Photography (review). (31 January 2016)

Calum Colvin: Jacobites By Name | Rating: ****

By

Monday 30 November 2015

DUNCAN MACMILLAN

From the deposition of James VII and II in 1688 to the death in 1766 of his son, James III and VIII, the Old Pretender, Scotland and England had alternative kings. Their supporters were the Jacobites. Rallying them to his flag, the Young Pretender, Charles Edward Stuart, son of James III and VIII, flared like a meteor across the skies in 1745 but crashed to earth at Culloden in 1746. Although paradoxically it gave it new glamour, this was really the end of the Jacobite cause. Charles Edward himself was never recognised as king, but died in 1788, disappointed and in near obscurity. A medal in the SNPG’s rich Jacobite collection commemorates the hopeless claim of his younger brother, Cardinal Henry Benedict, to be his heir in turn as Henry IX. The last in a royal line stretching back 400 years, he died in 1807.

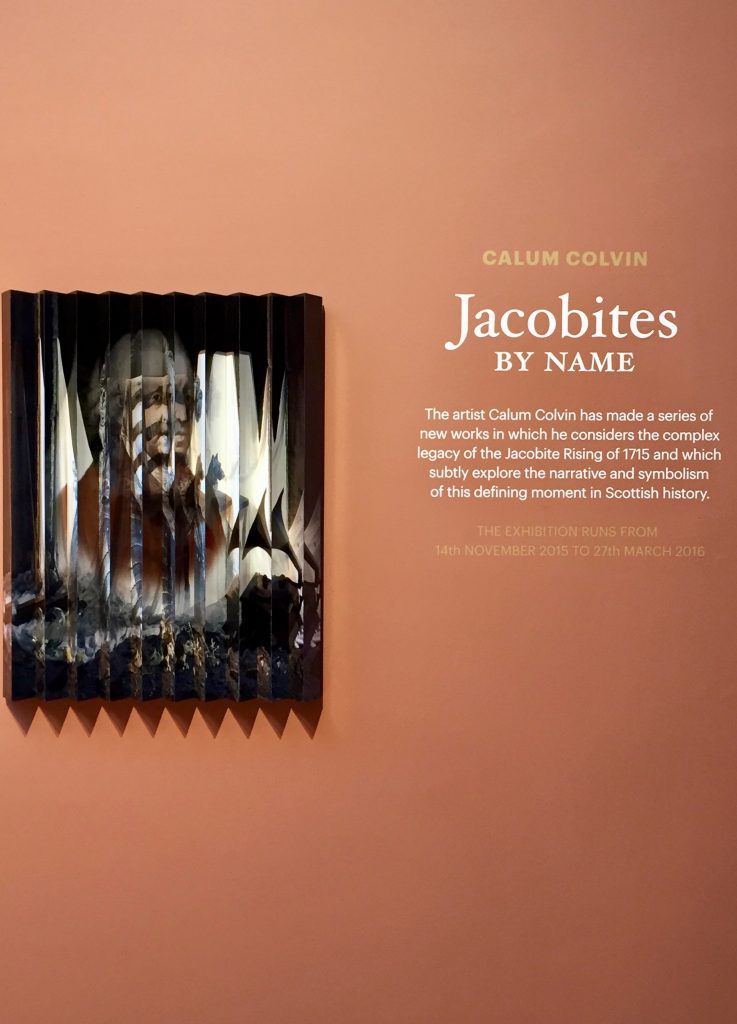

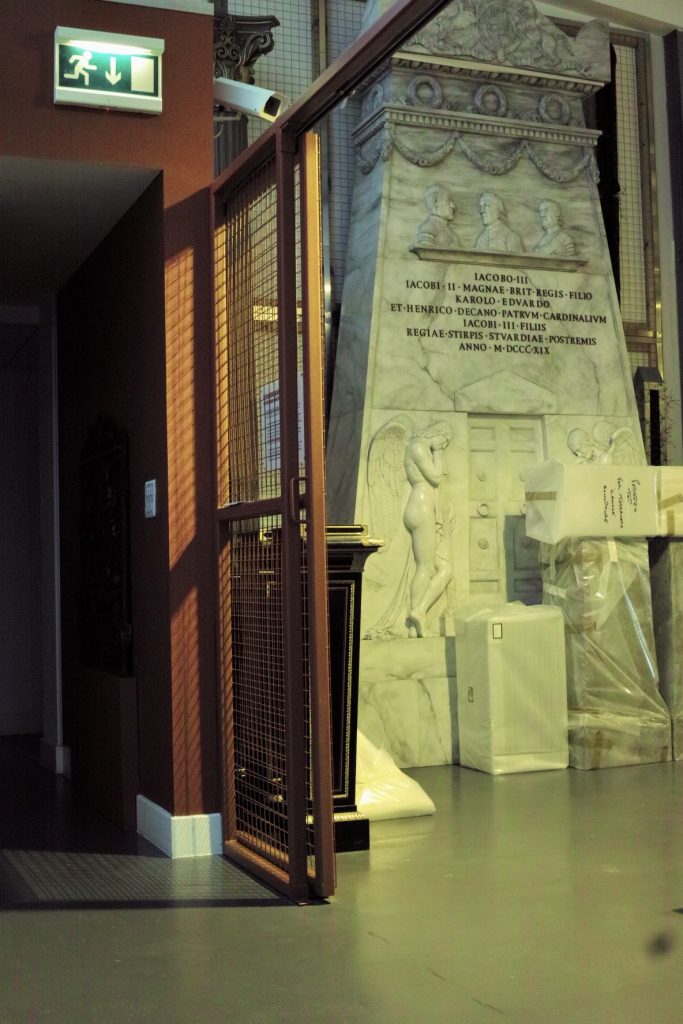

The Scottish National Portrait Gallery has now invited Calum Colvin to contribute a commentary to its Jacobite collection. Artists’ “responses” to historical works are generally lamentable. Not so with Colvin. He works by creating assemblages and then photographing them to make a single image and in his Ossian series, exhibited at the SNPG some years ago, he provided a subtle analysis of Scottish identity and the myths from which it is constructed: voices of the past, distorted as Chinese whispers as they echo faintly down the generations. So the Jacobites are the perfect subject for his art of allusion. Packing past and present in a single image, it illuminates both. The Stuarts were good-looking and much more glamorous than the dumpy Hanoverians. They were also more visually astute, but both sides used imagery as propaganda and in it, whether for or against, Charles Edward was usually clad in tartan. Thus, as the great lost cause of the Stuarts became identified with Scotland’s lost independence, the Prince’s tartan and his flight through the Highland landscape have provided the default imagery of Scottish identity and this is Colvin’s theme. A full-size replica of the Stuart tomb in St Peter’s stands in the Gallery entrance hall. Designed by Canova, George III contributed to the cost of the original, grateful, no doubt, to see the end of the Royal line of Stuarts, though, defiant even from the grave, the Old Pretender is twice named as James III on the tomb. Colvin has added a hologram to the tomb’s marble door so that it shimmers elusively between open and closed. Glimpsed inside, details of historic portraits, ghosts in the tomb, shift and dissolve. They appear to be slides on a screen. Their source is a projector on a stand, a motif that links several works here. Like the shadow play in Plato’s cave, it suggests that much that we take for reality is no more than a projection of the imagination, a story made up to explain the world. Thus Colvin deconstructs, not only the Stuart story, but also its persistent echoes in the present.

A model’s seat on a wooden dais, a stand-in throne, is also a frequent motif. In a portrait of James III and VIII, Mister Misfortune as he was called, his picture dissolves into a chair toppling off a step-ladder. If it is the ladder of ambition, the chair is made of glass, fragile hope of an elusive throne. To take its place among the historic portraits, this picture is hung in a gold frame. A portrait of Charles Edward in tartan is among several others framed this way. He wears the order of the Garter, but his face is little more than a cypher. A canvas on an easel and painting paraphernalia behind him suggest he is a construct like an art work. Antlers on the wall invoke the kitsch into which this imagined history sinks so easily. The whole decline and fall of the Jacobite cause is also presented in four contiguous images. They start with the handsome prince and end with a Hanoverian

charger trampling on his hopes, but in the foreground the inscription on a rusty sword reads, “Prosperity to Scotland and No to the Union.”

One group of works enlarges on contemporary propaganda engravings exhibited alongside. On paper, they are hidden behind doors to keep them from the light, adding a frisson of the clandestine Jacobite cause. In Lochaber No More I, Colvin incorporates a portrait of the young Prince Charles Edward shortly after his escape from Scotland. Still a warrior, he is in armour, but in Colvin’s version his image dissolves among dust sheets and the debris of his disappointed hopes. A Scottie dog, a piece of Scottish kitsch, sits in front of him and an old gramophone plays the lament that, it is said, brought the Prince to tears in later life. Other Jacobites are remembered here too. An engraving shows the ghastly scene of the execution of the Jacobite lords. Among them, dressed in tartan, Lord Balmerino went bravely to his death. Colvin shows him with a tartan shopping trolley and one of those awful tartan tammies with a ginger fringe beside him. Modern tartan has usurped his dignity. The projector stand has here been replaced by an ironing board. Enigmatically, Man Ray’s Surrealist spiked iron, The Gift, sits on it. At one point in his escape the Prince dressed as a woman. His picture in drag published by his enemies should have been a propaganda coup, but in a particularly lovely image, Colvin suggests it backfired. His glamour transcended gender.

The last in this series mirrors the first, but the half-seen portrait is now of the old and disappointed prince among the ruins of his hopes. The two portraits of the handsome young prince and his sad later self are also combined both in a hologram and in an anamorphic picture. Painted on a corrugated surface, as your viewpoint changes, both images are visible in this single painting. Colvin has also used a different kind of anamorphosis in a painting distorted like the skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors, but reconstituted for the viewer in a cylindrical mirror. Around it is written in Latin (backwards because of the mirror), “Tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis,” Times change and we change with them. These words also engraved on a “Jacobite” glass that he has made, are a suitable motto for the whole of this remarkable show within a show.

Colvin has also provided an enigmatic portrait of the Earl of Mar as preface to a new historical display about Mar, leader of the Jacobites in 1715. Part of the display is devoted to events around that first Jacobite rebellion and the main characters involved. But it also reveals that Mar was a man of wide culture with a deep interest in architecture and what we would now call town planning. Although he died in exile, he left his mark on Alloa, for instance, where his intervention laid the basis of the town’s future prosperity.

• Until 27 March 2016

https://sshop.org.uk/2016/01/31/calum-colvin-jacobites-by-name/

Public Lecture

Scottish National Portrait Gallery. (12 December 2015)

2016

Jacobites by Name, Artist’s Book

With contributions from Professor Fiona Stafford, Kathleen Jamie, Rab Wilson, James Lawson, Professor Calum Colvin and National Galleries of Scotland Senior Curator Julie Lawson.

Edition of 100, 86 pages. ISBN 978-1-906270-99-5.

Published by the Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland. Book Launch, Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

(11 March 2016)

‘Jacobites by Name’ Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

Marking 270th Anniversary of Battle of Culloden. (April 2016 – July 2016)

Press Features

BBC News website, (4 April 2016) The National, (5 April 2016)

Public Lecture, Inverness Museum and Art Gallery

(19 April 2016)

2017

‘Jacobites by Name’, The Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh (22 June 2017 – 7 October 2017).

● The Scotsman (Feature). (1 August 2017). ● Interviews posted on YouTube.

Public Lecture, Scottish Parliament

(16 August 2017)

‘Museography’ Exhibition

Five of the works from ‘Jacobites by Name’ were featured in a solo exhibition ‘Museography’ commissioned as part of a year-long programme marking the 150th Anniversary of The McManus, Dundee’s Art Gallery & Museum. This included two large canvases, a new, large embroidery (based on the smaller one made for the SNPG), and ceramic and glass pieces. This project led directly from the SNPG project and comprised of 20 works juxtaposed with the permanent collection and positioned strategically throughout the galleries, interrupting the viewing experience to create a contrast between the ambivalent visual nature of artworks and their typological classification.

(7 July 2017 – 29 October 2017)

McManus Permanent Collection

One of the canvases was among seven of Colvin’s works acquired by McManus for its permanent collection with the financial assistance of the National Fund for Acquisitions.