‘Ossian Fragments of Ancient Poetry’ was an exhibition in 2002 at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery of a series of twenty-five 40”x50” digital prints on canvas based on James Macphersons’ fact and/or fictional account of ancient Celtic mythology, ‘The Poems of Ossian and Related Works’ (1765). My intention with the work was to combine traditional photographic techniques with new digital technology in order to create a series of artworks that further blur the distinctions between painting and photography. Through this route, I sought to explore notions and ideas around history and identity (and, as a sub-theme, photography itself) which would question the role of ‘truth’ associated with these areas. The accompanying 64-page publication ‘Ossian Fragments of Ancient Poetry’ (ISBN 1 903278 35 X) has been translated into Gaelic, a first for any National Galleries publication. It contains colour reproductions of 22 of the artworks and a 10,000-word essay by Dr Tom Normand, University of St. Andrews. The first touring exhibition ever staged by the National Galleries of Scotland achieved national press, TV and radio exposure and toured internationally for six years. A conference was held around the exibition in Universite Paris Diderot and UNESCO Headquarters in 2005. The proceedings were published in Interfaces Vol 27, ‘Ossian: Then and Now’.

A CD ROM has been created in collaboration with NGS Education, financed by Highland Region, for use in Secondary Schools.

The exhibition was created with the aid of a Creative Scotland Award (2000). Support was also supplied by The Leverhulme Trust (Research Fellowship, 2000-2001), Fujifilm Professional Imaging, The Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, and Fine Art Research, University of Dundee.

Below is the exhibition Guide in English, Gaelic and French with notes written by exhibition curator Julie Lawson. These are also reproduced below, with the relevant images.

Ossian-exhibition-brochureOSSIAN FRAGMENTS OF ANCIENT POETRY

Calum Colvin’s new work is centred upon Ossian, the blind Gaelic poet of the third century AD. The verses were presented by James Macpherson in the 1760’s to a public enthused by the idea of a ‘Scottish Homer’ (Voltaire) and the Romantic thought that noble culture could be the product of a primitive age and a remote place. At the same time, Macpherson’s retrieval of fragments of the heroic culture provoked a questioning of their authenticity. The coincidence of doubt and affirmation is the theme of Colvin’s work. The erasure, suppression, neglect and recovery of a questionable memory of ancient Scottish history and culture provides a foundation upon which Colvin constructs an ironic, problematic and challenging commentary on modern Scotland.

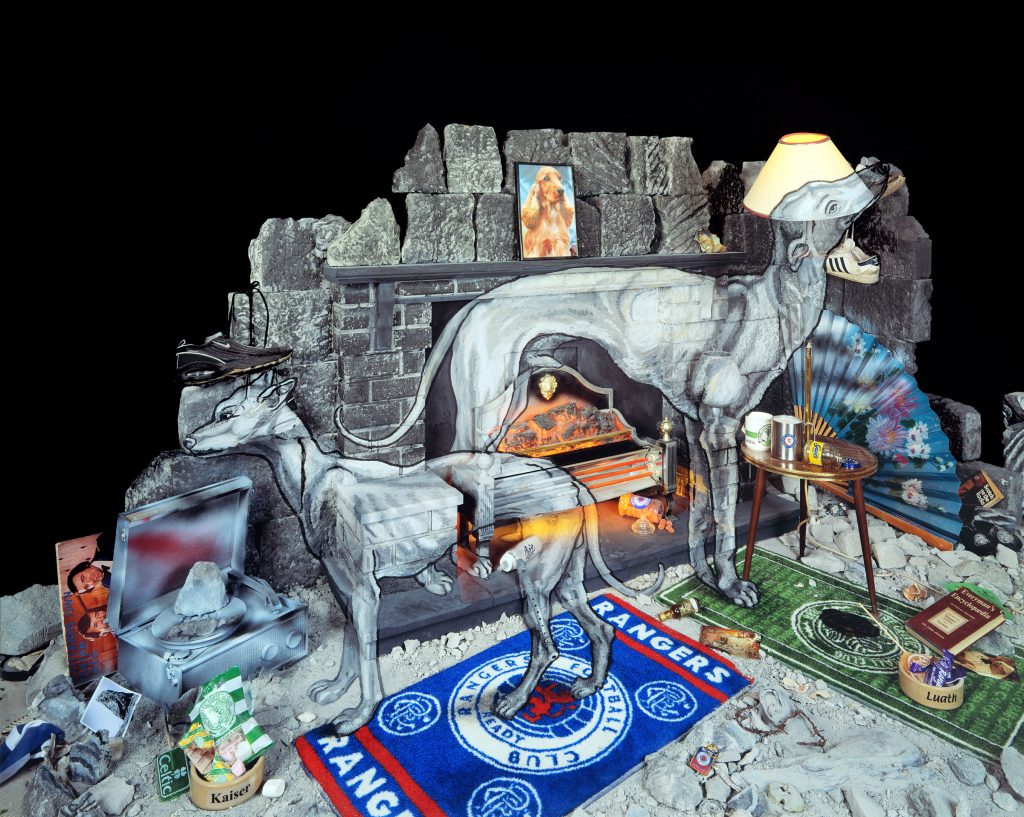

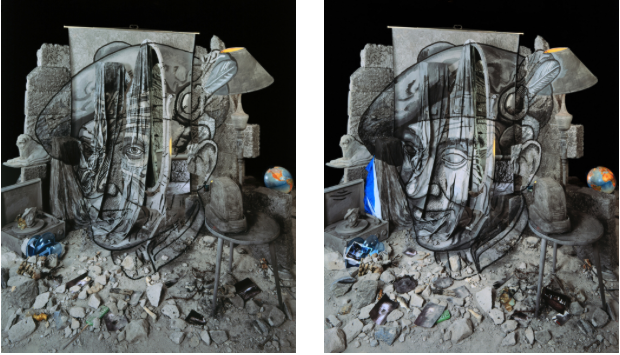

BLIND OSSIAN l-IX

In Ossianic poetry, elemental evocations of the land and its natural dramas are the backdrop for the noble deeds of ancient heroes. Colvin superimposes the face of Ossian upon a scene of stony desolation, which seems to metamorphose from depopulated landscape into the ruins of a building, or a building that stands incomplete, then into mysterious standing stones, or stones in a graveyard, possessed by ghosts. Ossian, the ancient Celtic bard, presides over this scene, now clearly visible, now vague and obscured.

The face of the poet is based on an etching by Alexander Runciman (1736-85). Colvin’s treatment acknowledges the artifice of the image. As an etching it contains the notion of something that is both present and absent – the ‘positive’ of the inked line and the ‘negative’ of the un-inked areas of paper. This becomes a metaphor for the fusion of the real and the fabricated in Macpherson’s ‘translations’ of Ossian, which are themselves emblematic of the mingling of the mythical and the factual in Scottish history.

SCOTA 01

The engraving, Melencolia I upon which Scota 01 is based is an allegorical self-portrait by the German Renaissance artist, Albrecht Diirer. Here, it seems the starting point for an allegory of the predicament of the contemporary Scottish artist. In the Diirer, the winged figure, a paradoxically earthbound angel, sits dejectedly, surrounded by the objects that represent the pursuit of knowledge and understanding: Mathematics, Astronomy, Philosophy, Geometry and the Arts. The image speaks in general terms about the futility of the search for Truth. Colvin’s figure is Scota, the mythical Egyptian princess from whom Gaels and Scots are descended. She sits in the bleak and decaying landscape of Blind Ossian, gazing into the prevailing gloom with the aid of the projector light that she wears like a miner’s helmet; and what she sees makes her despair.

Scota represents both Scotland and the artist when intellectual ambition and creative imagination are constrained by the limitations of the modern world. The work contains particular references to photography as an ostensible recorder of‘truth’, from glass negatives to the computer keyboard and the digitised copies of the portrait of Macpherson strewn on the ground. Digital manipulation makes possible a fake photography and a ‘fake’ reality.

Scota 01, 2001

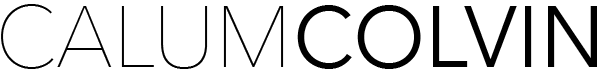

TWA DOGS

Robert Burns’s satirical poem The Twa Dogs demonstrates the absurdity of debates about social class and virtue. It takes the form of a dialogue between Caesar, a respectable upper-class dog, ‘o’ high degree’ and a ploughman’s collie called Luath, named after Cuchullin’s dog in Macpherson’s Fingal.

Colvin’s dogs, who stand with their backs to each other at a hearth made up of the same blocks that form the desolate landscape in Blind Ossian, represent the dualities in modern Scotland. Tom Normand writes: ‘In this clash, high and low culture, the classical and the modern world, the sublime and the ridiculous, are engaged in a fantasy duel. In turn, this becomes a saga of perpetual discord with Catholic and Protestant, the Highlander and the Lowlander, the Celtic Scot and the “North Briton”, competing over a contested and unattainable “identity”’. Colvin, he says, presents the prospect of‘a world wherein these two dogs will be locked in vicious and pointless combat forevermore. This, then, is the wretched bequest of Ossian’s dream, a world of unresolved conflict and perpetual despair.’

Twa Dogs, 2002

PORTRAIT OF ROBERT BURNS

Colvin has painted the head of Robert Burns (1759-96), based on the drawing by Archibald Skirving (1749-1819), based in turn on the famous portrait by Alexander Nasmyth (1758-1840) onto the landscape of Blind Ossian. The work contains references to Burns’s poems – red roses, green rushes, a red heart -all scattered in a wasteland, like personal effects scattered through the dust and rubble of a bomb site, testimony to a life and to a culture destroyed. Burns, the national bard, is present as the son and heir of Ossian, because of his romantic sensibility. The notion of Burns as an uncultivated, ‘natural’ poet – and thus the eighteenth-century equivalent of Ossian – was propagated during his lifetime. His contemporary, Henry Mackenzie, called him ‘the Heaven-taught ploughman.’ Inevitably, a mythology grows up around such a remarkable product of nature and heaven, and there are differing perceptions of Burns. Which is the real Burns? The republican who applauded the French Revolution, or the sentimental Jacobite of his best-loved songs? Ossian, it has been suggested, provided Burns with ‘a literary pose, in which he could express his feelings of pride, ambition and sensitivity without giving himself away directly.’ (David Daiches).

Portrait of Robert Burns, 2001

PORTRAIT OF SIR WALTER SCOTT

Colvin includes Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) in his pantheon of poets descended from Ossian. Scott took up Ossian’s mantle, and enthusiasm for his poetry spread like wildfire across Europe. Colvin bases his portrait of Scott on the classical bust of Scott by Bertel Thorvaldsen, which is now in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It is superimposed onto an architectural ruin set against a black night sky. Perhaps we are to think of Scott’s recommendation that we should view the ruins of Melrose Abbey by moonlight for the full romantic effect. The configuration of the stones also recalls the Scott Monument in Edinburgh.

Littered around the base, as if in mockery of the heroism of the austere portrait, are some irreverently playful items. Broken biscuits, emblematically frivolous in their confectioners’ pink and white, are strewn among the rubble. Colvin invites our meditation upon our predilection for putting images of Scotland’s great literary figures onto biscuit tins. He also includes a Jimmy hat, that ‘sardonic emblem of modern Scottish identity…[which] has become an ironic reference to cultural and national independence.’ (Normand) Colvin is reminding us that it was Scott who, on the occasion of the visit of George IV to Edinburgh in 1822, stage-managed the event and decked-out the entire population of the city in spurious tartan. The tartanry that is the legacy of this event means that, ‘Highland culture and history has become picturesque entertainment and the dissenting aspects of the Celtic world, with Ossian as its most pertinent representative, become a tourist’s trinket.’ (Normand)

Portrait of Sir Walter Scott, 2002

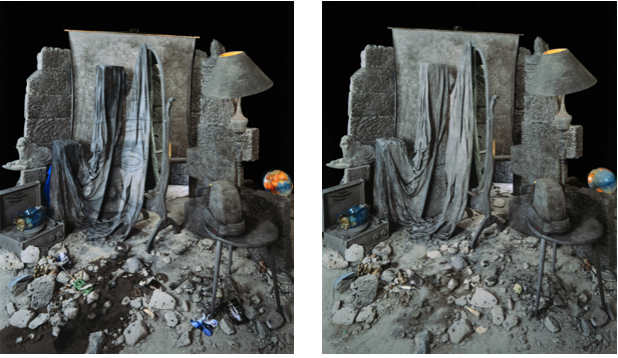

FRAGMENTS I-VIII

This eight-part work is an evolving portrait, a metamorphosis of the head of a Maori into that of a Highland Scotsman. Or rather, a pastiche of an anthropological engraving of a Maori mutates into a cliche of a ‘typical’ Scotsman. The Maori, whose tattoos are a visual echo of the lines in the head and beard of Blind Ossian, represents the ‘noble savage’ and echoes Ossian over again. The head is set not in a ruined landscape, but on a viewing screen. The objects that make up the set refer to ideas about authenticity, origin and ancestry. They are coated with a fine layer of grey dust. A fallout covers a world where only discrete fragments of former life remains. Colvin issues a stark warning of what an over-zealous concern with issues of origins and racial authenticity can lead to.

The Maori head is eventually replaced by that of the Highlander. Strewn around the ground are digital and analogue photographs of a portrait of James Macpherson. Normand writes: ‘ …the various personas of cultural identity meld and mutate. Simultaneously the symbols of national character and distinctiveness reveal both their diversity and their universality. Hence, the figure of “savage” Ossian folds into the “noble” Maori: Burns and Scott become twin of “Blind Harry” [Colvin’s working title for this piece which refers to Harry Lauder and the traditional music-hall Scotsman] who is now a composite poet, entertainer and cartoon. And all are kin and companion to the mysterious, controversial figure of James Macpherson’.

Fragments I – VIII, 2002

PORTRAIT OF JAMES MACPHERSON

The final work in the exhibition is a reprise of the starting point – the controversial figure of James Macpherson (1736-96) the ‘translator’ of the poems of Ossian. The portrait is based on that in the collection of the Scottish National Portrait Gallery which, not having been painted from life, is not strictly speaking an ‘authentic’ portrait. That it is a copy, by an unidentified artist, of a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds, is strangely appropriate. The irony is not lost on Colvin.

In his portrait of Macpherson, Colvin has created what Normand calls ‘ a compound forgery’. The image is placed against the background used for the ‘Maori’ and ‘Blind Harry’ of Fragments but this time, rather than paint the portrait onto the set, he has used ‘Photoshop’ to insert a portrait, manipulated to look like a painted work by Colvin the image-maker. As Normand writes ‘This is Colvin’s “forgery”, created to reprise the spectacular, surreal, and infamous debate surrounding Macpherson’s life and work’. *

Portrait of James MacPherson, 2002

CRUTHNI I – III

There is paradox of which Colvin is acutely aware for a modern artist concerning himself with issues of national identity and cultural authenticity. Modernism is to do with freedom from parochial narrowness. But there persists the need to know what the tradition is – to belong to it or to reject it. The Scottish artist, Colvin suggests, is adrift from cultural tradition. Indeed, it is this sense of alienation that is the premise of authenticity.

This triptych, whose title refers to a Pictish tribe, considers the problematic question of Scottish identity. The lines or striations that made up the face of Blind Ossian have reconfigured to form a fingerprint. The established means of authentication of identity, unique to every’ individual, also contains the idea of disappearance. It is the trace that remains after a person is no longer present at the scene of a crime. The double helix of the dna molecule is another symbol of modern methods of genetic identification. The Blind Harpist plays with an abacus rather than the golden strings of a lyre. Computation is indifferent to harmony. We are invited to ask whether the world is knowable to heart or head.

* /\s a final irony, it has subsequently been disclosed by the artist that the portrait of James Macpherson is not an ‘authentic’ Calum Colvin forgery after all. It was made, at his request, by someone else. So it too is a fake.

Notes written by Julie Lawson, exhibition curator, Scottish National Portrait Gallery

A fully illustrated catalogue is available to accompany this exhibition: Calum Colvin, Ossian: Fragments of Ancient Poetry by Tom Normand isbn 1 903278 35 x

Ossian-Catalogue-2Further Reading

Tom Normand: Memory, Myth and Melancholy: Calum Colvin’s Ossian project and the tropes of Scottish photography.

(RE-) MAKING OSSIAN

calum colvin

https://www.holycross.edu/sites/default/files/files/interfaces/colvin_essay.pdf