Over the course of my career representations of birds have frequently appeared within my work. These are sometimes present as detail and often as central motif. Generally, in the photographs, they function as symbols that signify various forms of human conceit, carelessness and folly. The series titled ‘Ornithology’ was created sporadically over a period of five years between 1994-1999, and foregrounds this symbolism through the technique of staged constructed tableaux orchestrated before, and recorded in front of, a large-format camera. Photographed with a 10”x8” De Vere camera onto transparency film, these constructed works use the foil of ornithological painting in order to present a symbolic narrative concerned with the social landscape of Scotland during that time. And also the role of art/photography, and creativity, within that milieu; that is, social commentary presented within a kind of ‘urban Audobon’ visual style. Works such as The Magnificent Frigatebird (1995), an image which meditates on the resilience of Scottish working-class culture, and Sacred Ibis (1995), which looks at the more desperate aspects of gambling and the National Lottery scratchcard obsession are rooted in the urban world of poverty, unemployment and de-industrialization and are presented as scenarios of hope and despair for ordinary people. Other images, such as A Caucus Race (1999) and Prometheus Bound (1999) are self-reflexive in terms of their concerns with the creative process, photography, digital and analogue procedures, and, painting and sculpture. Corvus Monedula (1999) and Mute Swan (1993) deal with the darker sides of love and desire. The combination of the fantastical with the familiar runs through all these photographs, but becomes the subject itself in The Common Runt (1999), which explores the glamour and banality of death, whilst Unidentified Aircraft (1994) inhabits that uncertain space between superstitious and scientific proof of impending doom. Whilst often dark in tone, dealing as they do with contemporary fragility, the works contain a seam of humour and adopt a style of painterly vigour to lighten the tone.

The Magnificent Frigatebird 1994

Massive seabird of warm tropical oceans and coastlines. Overall black with extremely long, deeply forked tail and angular wings. Male completely black with inflatable red pouch on throat (not seen away from breeding colonies) and bluish eyering. In good light, black coloration can show purplish sheen. Adult female has white chest and golden bar on shoulder. Young birds have white head and breast. Often soars for long periods and flies with slow wingbeats. Steals food from other seabirds. Surprisingly acrobatic during aerial chases despite its large size. Limited range overlap with Great Frigatebird (mainly offshore western Mexico and in the Galapagos); identification is complicated by age and sex variation. Adult males are extremely similar; females and immatures best identified by exact pattern of white on head and breast, bill color, and eyering color.

Female magnificent frigatebirds lay a single egg three to four weeks after the beginning of breeding season. The incubation period for this species is not recorded, but has been estimated at 50 days. Because female parent involvement continues for much longer than male parental involvement, females only mate every other year. Males rarely care for their young longer than six months and breed annually. Juveniles near mature mass before fledging. Age of sexual maturity is not known but none breed until plumage is in mature phase.

Usually silent at sea; harsh guttural calls during courtship.

A Caucus Race 1999

The Dodo bird inhabited the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, where it lived undisturbed for so long that it lost its need and ability to fly. It lived and nested on the ground and ate fruits that had fallen from trees. There were no mammals on the island and a high diversity of bird species lived in the dense forests.

In 1505, the Portuguese became the first humans to set foot on Mauritius. The island quickly became a stopover for ships engaged in the spice trade. Weighing up to 50 pounds, the dodo bird was a welcome source of fresh meat for the sailors. Large numbers of dodo birds were killed for food.

Later, when the Dutch used the island as a penal colony, pigs and monkeys were brought to the island along with the convicts. Many of the ships that came to Mauritius also had uninvited rats aboard, some of which escaped onto the island.

Before humans and other mammals arrived the dodo bird had little to fear from predators. The rats, pigs and monkeys made short work of vulnerable dodo bird eggs in the ground nests.

The combination of human exploitation and introduced species significantly reduced dodo bird populations. Within 100 years of the arrival of humans on Mauritius, the once abundant dodo bird was a rare bird.

The last dodo bird was killed in 1681.

“What IS a Caucus-race? said Alice; not that she wanted much to know, but the Dodo had paused as if it thought that SOMEBODY ought to speak, and no one else seemed inclined to say anything.

“Why”, said the Dodo,” the best way to explain it is to do it.”

In Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland all participants in the race have to run in circles until an arbitrary end is called and everyone is declared a winner; Alice has to give prizes to them all, and being declared a winner too she is solemnly taken and awarded back her own thimble.

Working with cameras as I do, I have witnessed a huge amount of technological change in photographic techniques, not least between the worlds of the digital and the analogue image. This picture dwells on the losses, gains and opportunities in this race toward the post-photographic future.

Corvus Monedula 1999

Common in open and semiopen habitats, from towns and wooded parkland to farmland and sea cliffs; often around stone buildings and chimneys. Nests in cavities. Distinctive, small social crow with contrasting, silvery-gray neck shawl and staring whitish eyes; juvenile has duller shawl and eyes. Walks confidently, and can be easy to see where not persecuted; associates readily with crows and Rooks. Flocks can number hundreds in nonbreeding season.

Although the birds normally pair for life, jackdaws in captivity tend to form same-sex pairs. Research in the Netherlands in the 1970s went a step further by concluding that such pairings occur in the wild and that among females that have lost their mates, 10% bond with other females and 5% form a same-sex ménage a trois. When a female is selected as a mate, she assumes the same rank as her partner and is accepted as such by all others in the group, upon whom she may impose her status by pecking.

Most typical call a very short, cheerful and resonant “kyak”. Timbre may vary by mood. Other sounds include subdued song with a large variety of sounds, and a grating alarm call “krrrrrrr”.

Sacred Ibis 1995

Ancient Egyptians revered Sacred Ibises. They mummified many of these birds and buried them in the tombs of deceased pharaohs, though they are now rare in Egypt.

Pure to dirty white feathers cover most of the body. Blue-black scapular plumes form a tuft that falls over the short, square-shaped tail and closed wings. The flight feathers are white with dark blue-green tips. Sacred ibises have long necks and bald, dull grey-black heads. The eyes are brown with a dark red orbital ring and the bill is long, downwardly curving, and with slit-like nostrils. Red bare skin is visible on the side of the breast and on the underwings. The legs are black with a red tinge. There is no seasonal variation or sexual dimorphism other than that males are slightly larger than females.

Sacred ibises are generally quiet birds. During the breeding season they produce a variety of vocalizations. In antagonistic situations, both sexes utter a variety of squeals, moans, and wheezes, sometimes described as: “whoot-whoot-whoot-whooeeoh” or “pyuk-pyuk-pek-pek-peuk”. Females make a series of “whaank” noises after the nest is built to attract the male, this is usually followed by copulation. Adults make a “turrooh” or “keerrooh” to call their offspring back to the nest. Adults make a high pitched “chrreeee-chree-ah-chreeee” to call offspring for feeding. They have also been observed making a loud croak during flight.

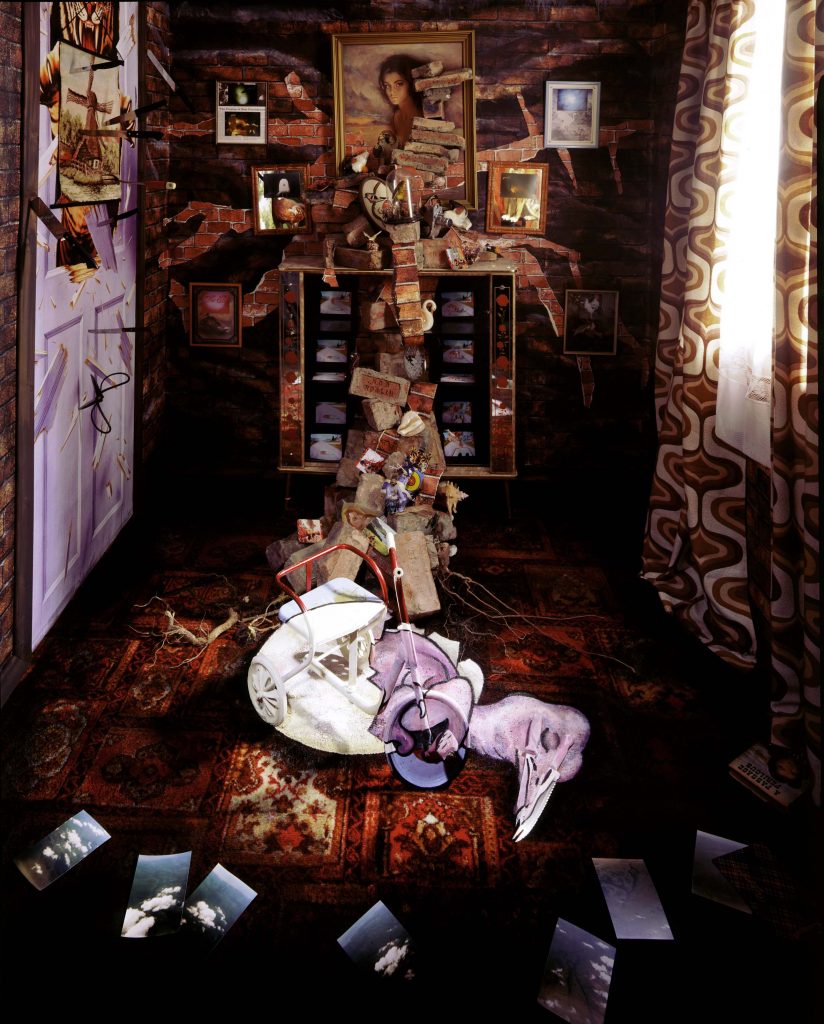

Prometheus Bound 1999

“I take my cue from deeds, not words.” Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound.

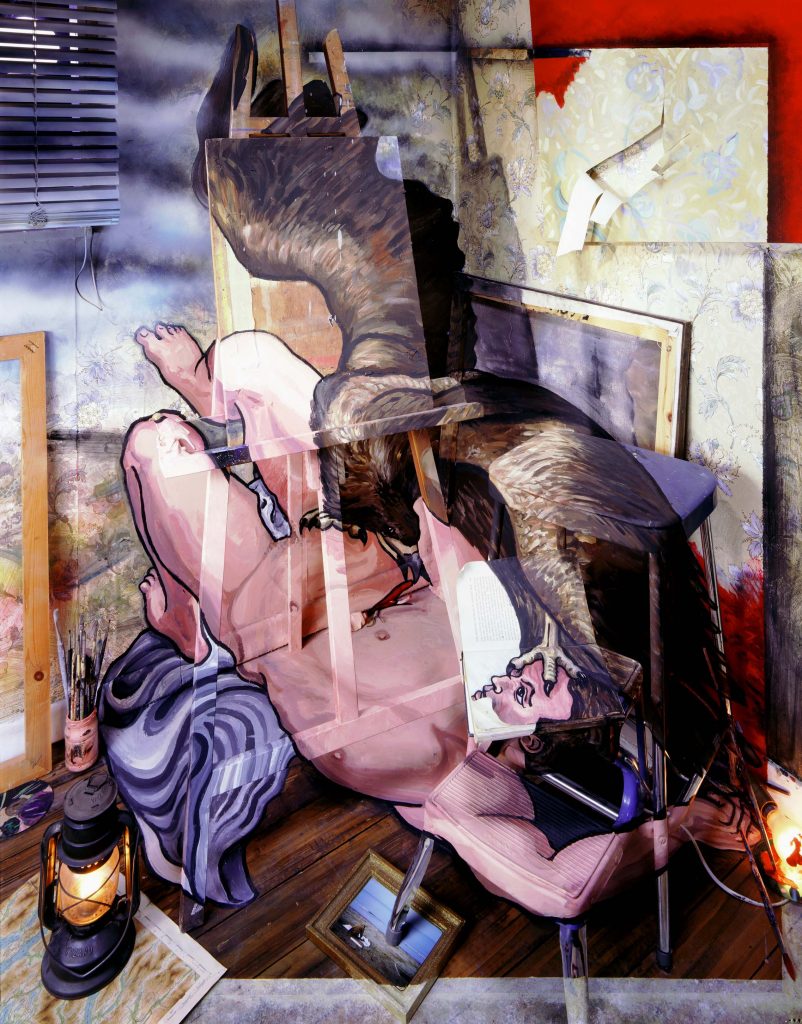

Common Runt 1999

Much of my work is based on accidental encounters with everyday objects and the narrative possibilities inherent in these. I first envisaged this image when I came across an unusual series of mini-books in the old Woolworths store in St Andrews. The books were entitled ‘They Died Too Soon’ and were a series of short biographies of famous pop stars whose careers had ended abruptly. Whilst contemplating the glamour and tragedy of these stars, I couldn’t help but ruminate on the more everyday aspects of this universal fate. So taking an image of the humble pigeon – the Common Runt, I created an image both surreal and ordinary, reflecting the extraordinary and mundane aspects of all existence.

f you are wondering how to kill pigeons then you might ask yourself if it is necessary to do so at all, and whether there might be a more effective method available. Our company can provide the most appropriate advice and offer you a cost-effective solution.

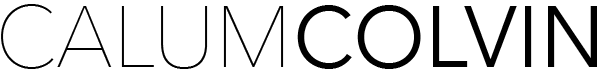

Unidentified Aircraft 1994

The work has its source in a little-known painting by the Montrose artist Edward Baird. Baird’s image of Unidentified Aircraft was painted in 1943, and reflected anxieties concerning bombing raids in World War II. In Baird’s surrealist work three figures, seen acutely and in profile on the lower horizon of the painting, search the sky for enemy bombers. The middle distance of the painting is a topography of the town of Montrose.

My version has repeated this context in the three portrait heads that rest in the bottom section of the photograph. However, the location is a sitting-room with television, display cabinet and assembled ornaments. The whole is over-painted in the grey-blue of a clouded, seemingly contaminated, sky.

In this domestic space I have painted an albatross (from Gustave Dore’s woodcut illustrations for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner), which glides across the scene observed by the onlookers. Surrounding this display are pictures and ornaments of swans and other birds. The underlying theme, and feel, of the photograph explores the idea of threat and apprehension; as associated with the mythic reputation of the albatross as a bad omen.

An underlying theme to the work is concerned with ‘atmospheric pollution’, overlaying the anguish of implied warfare in Baird’s work with a disquiet concerning ecological disaster and social perils which is echoed in the ambiguous newspaper headline ‘Air Strikes’ at the bottom of the picture.

Mute Swan 1993

When I made this work I was interested in the way that symbolism associated with the swan has multiple associations across various cultures. In some regions it was considered a feminine symbol associated with the moon. Its presence was a sign of intuition and gracefulness, considered feminine attributes. The goddesses Aphrodite and Artemis were sometimes accompanied by swans. More often, the swan was a masculine symbol. Its pure white color connected it to the sun, almost always a masculine deity. The swan was linked in ancient Greece to Apollo, god of the Sun. The work exploits this duality by incorporating masculine and feminine references within the artwork whilst making a more distant reference to Michelangelo’s ‘Leda’.